In the face of Israel’s escalating and destructive aggression in Palestine, the solidarity movement rising in Greece stands out with its remarkable strength and diversity. From blockade actions by dockworkers halting arms shipments to protests on the islands pushing back Israeli cruise ships; from student struggles against academic-military collaborations to participation in international flotillas aiming to break the siege of Gaza — this front of resistance draws not only on historical memory but also on the living veins of contemporary internationalism.

To better understand the dynamics behind this upsurge, and the grassroots resistance unfolding in the streets against Greece’s deepening alliance with Israel, we spoke with Antonis Faras from the “March to Gaza Greece” coordination group.

Historical memory

Why does the solidarity movement with Palestine have such a strong presence in Greece? What are the key historical, cultural, or political factors behind it?

The deep roots of Palestinian solidarity in Greece cannot be understood outside the country’s own history of war, displacement, and anti-imperialist struggle. During World War II, thousands of Greek refugees — including many from the Dodecanese, especially Kalymnos — fled to the Middle East, with a significant number finding refuge in Palestine. These were people escaping hunger, fascist occupation, and aerial bombardments. Many returned with vivid memories not only of hardship, but of solidarity among displaced and colonized peoples. These experiences contributed to an early cultural affinity between Greeks and Palestinians — not just as victims of war, but as subjects of shared struggle.

This historical memory later connected with the wave of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist sentiments that swept through Greece in the post-war decades. The resistance to the U.S.-backed military junta (1967–1974) shaped a political consciousness that viewed the Palestinian cause not as a distant conflict, but as part of a global system of oppression. Yasser Arafat was received in Athens in the 1980s a comrade in the broader fight against imperialism and national subjugation. Greece was among the first European countries to recognize the PLO and openly support Palestinian statehood, reflecting the alignment of popular sentiment with progressive foreign policy.

But this is not the whole story. Since the early 2000s, successive Greek governments — both conservative and social-democratic — have deepened military, economic, and political ties with Israel. Joint military exercises, arms deals, and energy cooperation (notably around the EastMed pipeline) reveal the extent to which the Greek state has reoriented its regional strategy in line with NATO and EU geopolitical imperatives. This alignment directly contradicts the enduring popular support for Palestine and exposes a deep rift between state policy and grassroots internationalism.

In that sense, the strength of the Palestinian solidarity movement in Greece is not simply a matter of historical memory or cultural affinity. It is also a form of resistance — against the militarization of foreign policy, against the neoliberal restructuring of the Eastern Mediterranean, and against the co-optation of Greece into imperialist alliances.

'Not a homogenous movement'

Around which slogans and demands does the solidarity movement coalesce (ceasefire, embargo, ending academic-military collaborations, blocking the transfer of weapons through ports, etc.)? Who are the main subjects of this movement?

The central axis of the movement is the call for solidarity and freedom for Palestine — not in abstract humanitarian terms, but through the recognition of the Palestinian people’s right to resist occupation, apartheid, and ethnic cleansing. This includes the immediate end to the blockade of Gaza, the end of Israeli occupation in all its forms, the right of return for all Palestinian refugees, and the vision of a free, independent Palestine across its historical territory, with full rights and justice for all its inhabitants.

A second, equally crucial dimension is the demand for the political, economic, and cultural isolation of the Israeli state. Israel is not viewed simply as an occupying power but as an integral part of the global security-industrial complex, deeply embedded in the machinery of NATO, the United States, and the European Union. In this context, the movement in Greece calls for the cancellation of all bilateral agreements with Israel — whether military, economic, academic, or technological — and supports the international BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) campaign as a strategic and ethical imperative. This includes efforts to end academic and military collaborations between Greek and Israeli institutions, to prevent the docking and refueling of Israeli warships in Greek ports, and to block the transfer of weapons and military equipment through infrastructures such as the port of Piraeus.

These demands are framed within a broader critique of the war economy and the ongoing militarisation of the West. Support for Israel is seen as symptomatic of a larger process — one in which life itself is increasingly shaped by militarism, surveillance, and the logic of permanent war. The solidarity movement thus also positions itself against the militarised restructuring of the Greek economy, against NATO’s expanding role in the region, and against the normalization of military-industrial policy across Europe. In short, to stand with Palestine is also to oppose the global trajectory of war and repression being led by the so-called democratic West.

The composition of the movement reflects this complexity. It is not a unified or homogenous subject, nor does it speak with a single voice. Rather, it is a constellation of actors and forces, ranging from political collectives and left organizations to student assemblies, cultural workers, migrant communities, and trade unionists. Dock workers in particular have taken visible action by refusing to handle cargo linked to the Israeli war machine. Students have mobilized against academic normalization with Israeli institutions. Artists and intellectuals have built bridges between cultural resistance and political solidarity.

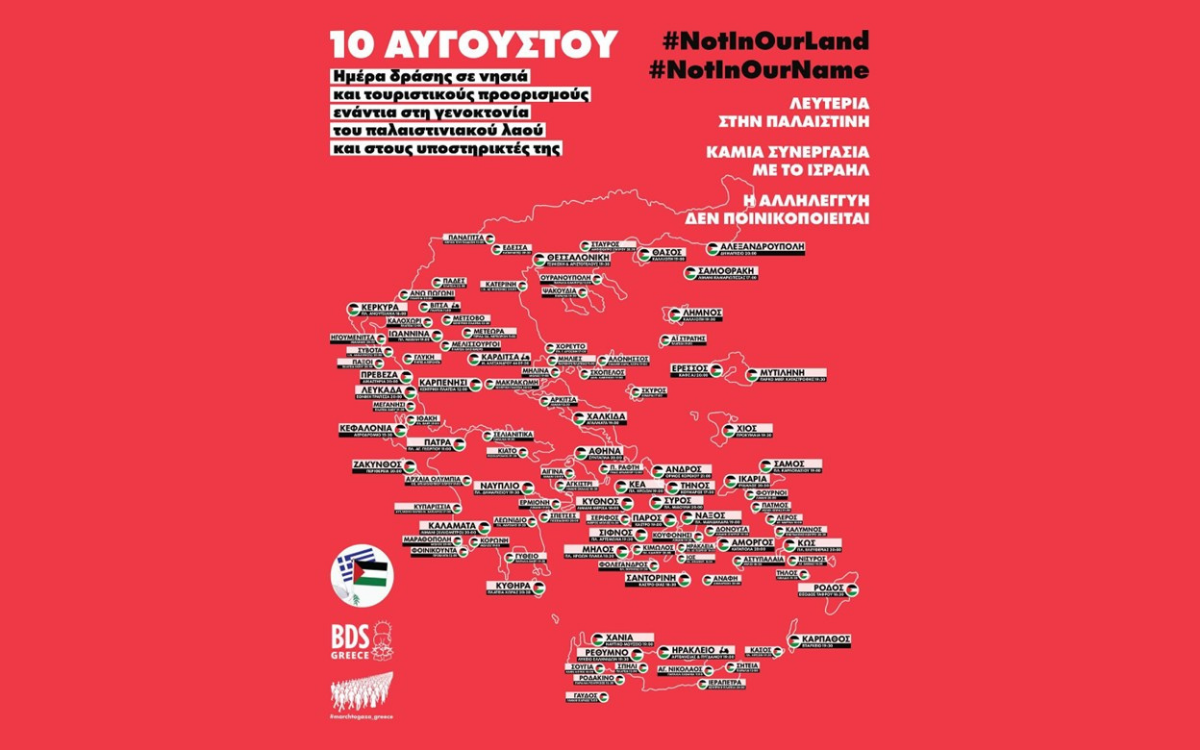

But perhaps most importantly, there is an expanding and increasingly vocal popular base that identifies with the Palestinian cause. From massive demonstrations in the streets, to banners in football stadiums and viral campaigns online, Palestine has become a political symbol for a much wider refusal: a refusal of complicity, of imperialism, and of the violence being done in our name. In the 10th of August a nationwide Not In Our Name, Not In Our Land call, swept the country with 120 demonstrations - which is unprecedent for Greece.

Is there a practical division of labor or coordination mechanism among these actions?

While the movement remains largely decentralized, there are growing efforts toward coordination. Different forces — from student groups and political collectives to dock workers and migrant communities, as mentioned above — intervene from their own terrain, creating an informal but effective division of labor. Mobilisations, blockades, and campaigns often emerge through autonomous initiative, but converge around shared political goals.

The most promising effort toward sustained coordination is the March to Gaza Greece initiative, which has begun to operate as a broader political space — bringing together diverse actors, organizing nationwide actions, and articulating a unified pro-Palestine radical position. Though still in formation, it points to the potential for deeper strategic alignment without sacrificing the movement’s grassroots dynamism.

'Piraeus will not become a hub for imperialist wars'

We know that the loading of munitions onto ships bound for Israel at the Port of Piraeus has been prevented multiple times. How were these actions organized?

These blockades were the result of organized, militant intervention by dockworkers, trade unions, and solidarity networks, with the workers’ union at COSCO (ENEDEP) playing a central role. In July 2025, ENEDEP identified a ship — the Ever Golden, flagged in Panama — that was suspected of transporting military-grade steel to Israel. After inspecting the ship and confirming that the cargo had already been transferred to another vessel (Cosco Shipping Pisces), the union issued a public call for mass mobilization at terminals II and III of the port.

Hundreds responded — including student unions, political collectives, the Piraeus Labour Centre, and ordinary people — forming a powerful physical and political blockade. Their message was clear: Piraeus will not become a hub for imperialist wars, and the Greek working class refuses to have its labor implicated in genocide. The dockworkers’ slogan, “We will not stain our hands with blood,” captured the moral and political stakes of the action.

This was not an isolated incident. It followed an earlier intervention just days before, and reflects a growing pattern of coordinated refusal to allow the port — privatized and operated by COSCO — to be used for the transport of weapons and military material to Israel.

Another significant example was the protest against the Israeli cruise ship Crown Iris in the Aegean islands (Crete, Rhodes, Syros), which resulted in the ship being unable to dock. Were these actions carried out only by local initiatives, or is there an organized or at least coordinated struggle between the mainland and the islands?

The protests against the Israeli cruise ship Crown Iris — which faced resistance in multiple ports across the Aegean — were rooted in local mobilizations, but they were far from isolated. In Syros, for example, residents issued a public call for mobilization against the ship’s arrival on July 22, denouncing the normalization of Israeli tourism while a genocide is unfolding in Palestine. Their statement was clear: “As residents of Syros, but above all as human beings, we act locally to stop the destruction caused by this genocidal war.” They linked the protest not only to solidarity with Palestine, but also to Greece’s own political responsibility, denouncing the ND government’s direct and indirect complicity.

What is politically significant is that these mobilizations were coordinated across multiple islands and ports, responding in real time to the ship’s itinerary. While there is no formal national structure directing them, a shared political direction, rapid information-sharing, and common slogans allowed for an effective, decentralized blockade. Each island — Syros, Rhodes, Crete— acted autonomously, but with awareness of the others, creating a moving front of resistance that forced the Crown Iris to reroute or cancel stops.

Moreover, the protests were not only against the ship itself, but against the broader attempt to normalize apartheid through tourism — at a time when tens of thousands of Palestinians, including at least 18,000 children, have been killed. The residents of Syros explicitly opposed the restrictions placed by port authorities to facilitate the cruise’s arrival, demanding free movement for locals and denouncing the silencing of dissent.

The government called these actions antisemitic and racist, in line with their view of the need of strategic partnership with Israel. So, they chose to slander and repress these mobilisations. In Rhodes, repression was even more visible. Police protected the cruise ship’s arrival by physically attacking protesters/ At the same time, Israeli passengers themselves engaged in violent and racist behavior — including verbal harassment of activists, and even physical assault, as in the case of a shop owner in Rhodes who was attacked for displaying a sign reading “Zionists not welcome.”

Mass protest on Wednesday morning by unions and mass organizations at the Port of Volos against the docking of the cruise ship Irish Crown, which is carrying IDF soldiers

— PAME Greece International (@PAME_Greece) August 13, 2025

The murderers of the Palestinian people and the peoples of the Middle East are not welcome!

No cooperation… pic.twitter.com/qsY0KwIYB8

'A toxic mixture of anti-Turkish nationalism, Islamophobia, and militarism'

How does Greece’s military-strategic alignment with Israel (air defense projects, the Eastern Mediterranean energy equation, the Greece-Cyprus-Israel trilateral axis) affect grassroots solidarity with Palestine? Does it generate nationalist counter-reactions in Greece?

Greece’s deepening alignment with Israel — militarily, economically, and geostrategically — poses a direct challenge to the Palestinian solidarity movement, but it also sharpens its relevance. From joint air defense programs and arms deals to energy cooperation in the Eastern Mediterranean, the Greece-Cyprus-Israel axis is now a cornerstone of NATO’s regional strategy.

This alignment creates two parallel effects. On one hand, it exposes the hypocrisy of the Greek state, which invokes historical memory and “solidarity with oppressed peoples” while arming an apartheid regime. This contradiction fuels popular anger and reinforces the legitimacy of grassroots resistance — particularly among students, workers, and internationalist movements that see Palestine not as an exception, but as a symptom of broader imperialist logics.

On the other hand, state narratives around “shared security interests” and “energy sovereignty” do enable nationalist and militarist counter-reactions. Sections of the Greek far-right, as well as parts of the mainstream, frame Israel as a strategic ally against “common enemies” — namely Turkey — and portray Palestinian solidarity as a threat to national interests. This logic feeds a toxic mixture of anti-Turkish nationalism, Islamophobia, and militarism, which the Greek state actively cultivates to justify its regional role.

However, this nationalist discourse doesn’t dominate unchallenged. In fact, grassroots solidarity with Palestine increasingly positions itself against both Israeli apartheid and Greek nationalism. Activists denounce the trilateral axis as part of a wider system of militarized accumulation — where fossil fuel extraction, surveillance technologies, and border militarization are inseparable from the war on Palestine.

In that sense, solidarity with Palestine in Greece today is not just about moral support — it is about opposing the material infrastructures of war and racism, including those rooted in the Greek state itself.

Greek left remains fragmented

How decisive is the role of political parties (KKE, SYRIZA, MeRA25, etc.) and trade union confederations in this process?

The role of political parties and trade union confederations in the solidarity movement is shaped by fragmentation, contradictions, and uneven commitment. SYRIZA, once dominant in the Greek left, is now politically marginal — polling under 5% — and carries historical responsibility for initiating the strategic alignment with Israel during its time in government. Its transformation into a liberal party of state management has largely cut it off from grassroots internationalist struggles.

MeRA25 holds clearer political positions on Palestine, consistently denouncing Israel’s war crimes and Greece’s complicity. It has supported key initiatives and mobilisations, including calls for sanctions and arms embargoes. However, its limited organizational depth and lack of militant infrastructure prevent it from playing a decisive role in shaping or coordinating the movement on the ground.

The extra-parliamentary left, on the other hand, is rich in political clarity and militant commitment — but remains divided, fragmented, and often trapped in its own ideological boundaries. Many groups prioritize political autonomy over coordinated action, leading to parallel mobilisations, overlapping campaigns, and missed opportunities for unified impact. The same can be said for trade union confederations, which either maintain a cautious distance from internationalist struggle or reproduce the same internal divisions.

The KKE, as one of the strongest organized forces on the left, plays a significant but contradictory role. It participates actively in mobilisations and raises the question of imperialist complicity, but often does so through practices of separation and duplication. An example of last years’ Motor Oil protests is telling: rather than join a common mobilisation against the company’s fueling of US military ships destined for Israel, the KKE organized a separate protest just hours apart — despite shared demands and location. This kind of sectarian reflex weakens the movement, especially at a time when unity is urgently needed.

This pattern is not limited to the KKE, but it reflects a broader failure of the Greek left to build a unified front capable of exerting real pressure — whether through mass mobilisation, political campaigns, or coordinated civil disobedience. In contrast to movements in countries like Spain or Ireland, where diverse forces manage to act together while maintaining their political autonomy, the Greek landscape remains deeply fragmented.

But if we are to move from symbolic solidarity to material pressure on Israel and the Greek state, what is needed is not just more protests, but more convergence. A united front for Palestine in Greece — grounded in action, not abstract agreement — is both possible and necessary. The Palestinian national movement has achieved forms of unity even in conditions of siege and civil war. That the Greek left and trade unions fail to do so in conditions of relative stability is a political failure we must overcome.

Mitsotakis' loyalty to Netanyahu

Recently, Prime Minister Kiriakos Mitsotakis announced that Greece would recognize the State of Palestine “at the right time.” What do you think he means by “the right time”?

When Prime Minister Mitsotakis says Greece will recognize Palestine "at the right time," what he actually signals is indefinite postponement under the guise of strategic caution. This is a political evasion that exposes the cynical hypocrisy of Greek foreign policy.

Let’s recall: the Greek Parliament unanimously voted in favor of recognizing the State of Palestine in September 2015, almost a decade ago. That decision has never been implemented by any government since — not by SYRIZA, which first deepened strategic ties with Israel, and certainly not by the current ND administration, which has brought that alignment to its most extreme point.

Mitsotakis himself is now one of Netanyahu’s most loyal supporters in Europe, rivaled only by some German officials. In his most recent interview (17 September 2025), he refused to use the term “genocide” for what is happening in Gaza — calling it a “humanitarian catastrophe,” while insisting Israel is “a democracy responding to an unimaginable act of violence.” This framing reproduces the core talking points of Israeli state propaganda and denies the findings of international law. The UN Human Rights Council’s independent inquiry has already confirmed that Israel’s actions in Gaza meet four out of five criteria for genocide under the 1948 Genocide Convention. To dismiss this as a matter of “subjective opinion” undermines the legitimacy of international law itself.

What Mitsotakis means by “the right time” is in fact when it is no longer politically costly to do so — or when the move can serve Greek geopolitical interests without disrupting relations with Israel or the US. In the meantime, his government refuses even the mildest forms of accountability, such as supporting EU sanctions or suspension of trade agreements with Israel. He publicly questioned whether even a partial suspension of the EU-Israel Association Agreement would “serve the interests of Europe and of our country.” In reality, Mitsotakis is currently to the right of Ursula von der Leyen on this issue — a position that should alarm anyone who believes in basic internationalist ethics, let alone left-wing politics.

But recognition without action is not solidarity. It is empty symbolism used to appease domestic and international pressure while continuing to arm, train, and do business with an apartheid state. The only recognition that matters is political pressure that costs something: arms embargoes, economic sanctions, the cancellation of military cooperation, and a clear end to the Greece-Cyprus-Israel strategic axis. Without these, “recognition” is little more than a diplomatic performance.

Ultimately, the “right time” was ten years ago, when Parliament passed the recognition resolution. The fact that successive governments — both social-democratic and conservative — have refused to implement it shows that Greece’s foreign policy is not shaped by democratic mandates or legal obligation, but by its subordination to NATO and its complicity with Western imperialism.

The question now is not when Greece will recognize Palestine — but how long it will continue to shield a genocidal regime under the language of pragmatism and “national interest.” Because when an entire people is being exterminated, the only morally and politically coherent time to act is now.

'We managed to touch a nerve in Greek society'

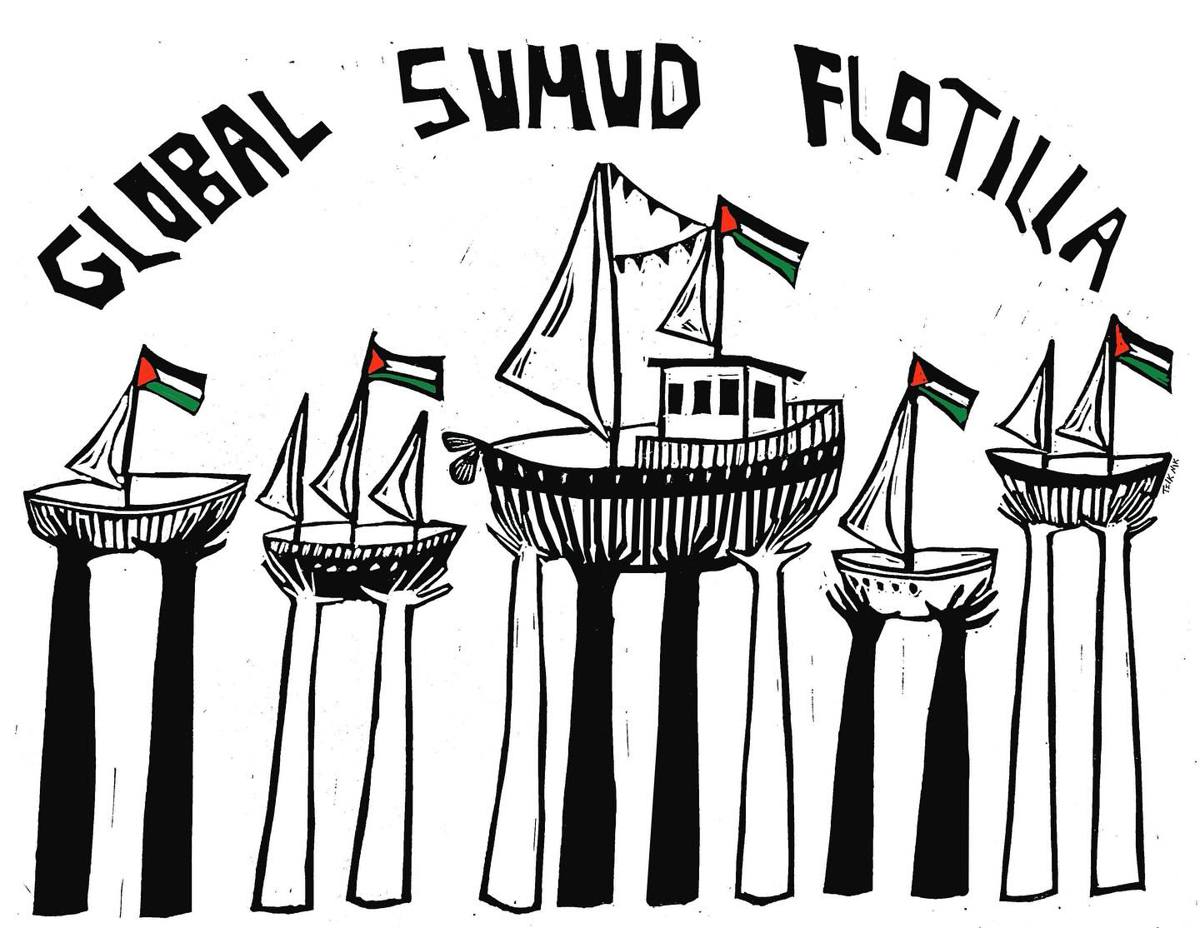

During these mobilizations, are there international contacts or joint campaigns being established? For example, has there been participation from Greece in the Sumud Flotilla, or is there expected to be?

Yes — and this is one of the most hopeful and politically significant developments of the last months. The solidarity movement in Greece is becoming increasingly embedded in international networks of action, and the most powerful example of this is the active participation in the Global Sumud Flotilla (GSF) — the largest coordinated sea convoy ever attempted to break the siege on Gaza.

The March to Gaza Greece initiative, of which I’m personally a member, has managed to touch a nerve in Greek society, reigniting the long tradition of anti-colonial internationalism that runs deep in the Greek left and popular memory. After starting — symbolically and literally — with a march from Cairo that aimed to reach Gaza by foot, we joined forces with the Sumud Convoy and the Freedom Flotilla Coalition, building the foundations for a common promise: to sail a fleet of ships toward the besieged Gaza Strip, not just with aid, but with a clear political demand — end the genocide, lift the blockade, and support Palestinian resistance.

Our national campaign is now underway, and six ships are already preparing to sail. One of them, Oxygono (Oxygen), sails under the Palestinian flag and represents something more than logistics. It is carrying the breath of thousands — the workers, students, and families who filled Greek squares after the Tempi train disaster, those who took to the streets on August 10th in solidarity with Gaza, and all those who understand that Palestine is not only about Palestine. It is about justice, memory, and survival in a world being suffocated by war, borders, and impunity.

The Greek mission has set sail from Syros. We know we will face obstacles from the Greek state, which has aligned itself openly with Israel’s genocidal regime. We know we may face attacks from Israeli forces, who have repeatedly boarded and sabotaged past flotillas. But we also know that our strength lies in people watching — in mass visibility, pressure, and solidarity from below. Every eye on the flotilla is a form of protection. Every voice raised for Gaza is part of the collective shield.

This is not just humanitarianism. These boats carry not only medical supplies — they carry the solidarity of the Mediterranean and of the world’s peoples, they carry the demand for an end to apartheid, and they carry the hope that the resistance of the Palestinian people will ultimately prevail.

We see Global Sumud Flotilla as a frontline of international struggle. And Greece, despite the complicity of its state, is part of that frontline — because its people refuse to stay silent.

What will be the strategic priorities of the movement in the coming period? Ending university-industry/military collaborations, maintaining permanent oversight over ports and logistics routes, exerting pressure on local governments and tourism policies, consumer boycotts… In your view, what is the most realistic achievement?

Our strategic priorities follow the lead of the Palestinian resistance. That means focusing on ending military-industrial collaborations with Israel, blocking arms shipments through ports, pressuring local governments to cut ties with apartheid institutions, and building mass support for boycott campaigns.

The most realistic goal now is to make complicity visible and politically costly — turning every site of normalization into a site of confrontation. (DS/VK)