From 2017 to 2020, artist Fatoş İrwen was jailed in Diyarbakır, her birthplace in the Kurdish-majority region of southeastern Turkey, for demonstrating against war and in support of LGBTI+, women, and mother tongue rights, where Kurdish and its speakers have been oppressed by a multigenerational regime of state violence.

"My daily routine began at six in the morning," İrwen said. "As soon as I stepped into the courtyard to exercise, I would gather the things left behind by the birds and the wind and set them aside. Bird feathers, plant fragments, various insects I found dead, bird eggs, twigs, pieces of stone thrown from somewhere, etc. I lived my life in prison with great care and discipline."

Her story begins in the historic district of Suriçi in Diyarbakır, the oldest part of the city that preserves Hurrian and Assyrian ruins from the Late Bronze Age. İrwen grew up in the heart of this ancient settlement with nine siblings, an extended family that grew as her older brothers had families of their own and continued to live at home with their wives and children.

Memories of Suriçi

İrwen remembers her childhood with a bittersweet fondness. "Over 20 people lived together under one roof. It was an environment where everyone would mix up each other's names when calling out to one another. This amused me greatly. Especially my mother, who would say at least three names when trying to call one of us," she said.

"The connection I had with places was very special. It became the foundation of my work. We lived in a house with a courtyard. These were structures where the boundary between the street and the house was blurred. The labyrinthine structure of the streets and the fact that the houses had so many details to hide in always inspired me to create new spaces."

The complex history of İrwen's birthplace serves as the backbone of her work as an artist, a path that she chose with great difficulty, rising out of an atmosphere that was utterly dismissive or ignorant of creative careers. Yet, in an eccentric uncle, she found a kindred spirit.

"My father's youngest brother was my uncle Fettah. I don't think I know anyone more interesting than him in this world. He was a person I remember with a lot of strangeness and love. He was a kind of madman," she remembered.

"He would sing folk songs to me with his saz. He would take my hand, walk me through the streets of Diyarbakır, and tell me stories. He had a great interest in mythology, art, and history. He would hold my hands, tell me that I would become an artist when I grew up, and kiss me with admiration."

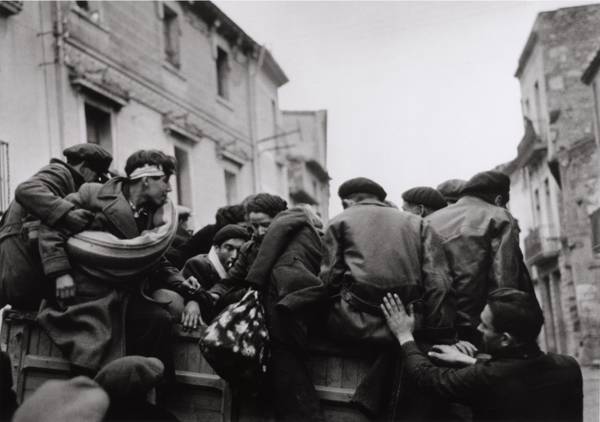

From 2015 to 2016, İrwen's childhood neighborhood of Suriçi was rocked by clashes between Kurdish militants and the state. Heritage sites were damaged and İrwen was catalyzed to act in solidarity with fellow advocates for peace and human rights.

The artwork she would produce while in prison, together with her entire body of work so far is a testament to the cultural survival of women and Kurds in Turkey, although she shies from direct sociopolitical representation. Instead, as an artist, she speaks on behalf of her individuality, which has contributed to her success in the art world, a sector that she critiques with sensitive, empathic judgement.

'I am interested in the social reality in which I grew up'

"In fact, almost all of my works contain excerpts from my own personal life. A title such as ‘The Oppression of the Kurds’ would be crude and inaccurate. It would be more accurate to say that I am interested in the social reality in which I grew up, power, the state, the political environment, feudalism, traditionalism, and the situations and psychological processes I experienced as an individual struggling for freedom within all of this," she explained.

İrwen is currently showing two artworks, “Cannonballs” (2019) and “Cracking Borders, 40s” (2022) at the Arter art museum in Beyoğlu, İstanbul.

Her artwork, on display in the heart of Istanbul’s cultural sector, is composed of her hair an act of solidarity with fellow female prisoners, and soil gathered from Diyarbakır, specifically the Hevsel Gardens of Mardinkapı Cemetery, with reference to environmental destruction and cultural resilience in her home region.

The artwork, shown as part of the Under Pressure Above Water exhibition, continues in the midst of Turkey’s ongoing resolution process to the Kurdish question, culminating in a fire ceremony in July where Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) members burned their weapons, one step closer to ending an ongoing conflict that has continued for over 40 years.

The exhibition, curated by Nilüfer Şaşmazer, can be seen at Arter until Jan 11, free of charge. (MH/VK)