Yusuf Çelik was only 14-years-old when a right wing mob burned alive Aydın Taşkesen, a Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) supporter, in Çelik’s hometown of Erzurum. Although disturbing, and one of Çelik’s first memories of vigilante violence, it wouldn’t be the last or only instance that pushed Çelik to pursue journalism.

Five years later, Çelik would publish their first story about a queer student’s experience in university dorms and embark on what has now been a three year career with an impact well beyond its short tenure.

The independent LGBTI+ reporter has published in outlets such as Özgür Gelecek, KaosGL, Velvele and Muzır.

“Being a journalist in Turkey is already challenging and then being a queer journalist or involved in queer journalism in Turkey is much more difficult,” Çelik said.

'Year of the Family'

This is especially relevant during the ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) 2025 “Year of the Family” campaign, which focuses on promoting what they deem “traditional Islamic family values.” This has meant a few financial incentives to increase birthrate, but also a litany of anti-feminist rhetoric and anti-LGBTI+ proposals, drawing strong criticism from feminist and LGBTI+ activists.

Queer identity and relationships are not directly illegal in Turkey. However, vague misdemeanor laws are sometimes mechanized to oppress the LGBTI+ community under the guise of “public morality.” The AKP attempted to exacerbate this by specifically referring to LGBTI+ communities in the draft 11th Judicial Package.

After reactions from the LGBTI+ community and rights groups, provisions targeting LGBTI+s were reportedly removed from the package, which has yet to be introduced. These provisions included criminal penalties for "promoting behavior against innate biological sex," which could potentially target LGBTI+ activists as well as journalists covering LGBTI+ issues, and restrictions on gender reasssignment treatment.

Proposed judicial package introduces criminal penalties targeting LGBTI+ community

Even though anti-LGBTI+ articles may have been removed from the agenda for now, the fight is likely not over according to Çelik. “They’re going to continue … to try again and again to use this approach," they said. "The year of the family has become the decade of the family."

In this “Year of the Family” 2025, Çelik has found themself under arrest three times during their reporting and the instances of police brutality they’ve suffered is just as numerous.

During the March protests against the arrest of the İstanbul mayor, Çelik said they were pinned to a tree by 10 officers despite sporting a visible camera and press badge. Screams that they were a journalist were also not enough to protect them from an injury to their right shoulder and a mutilated finger that still has not recovered.

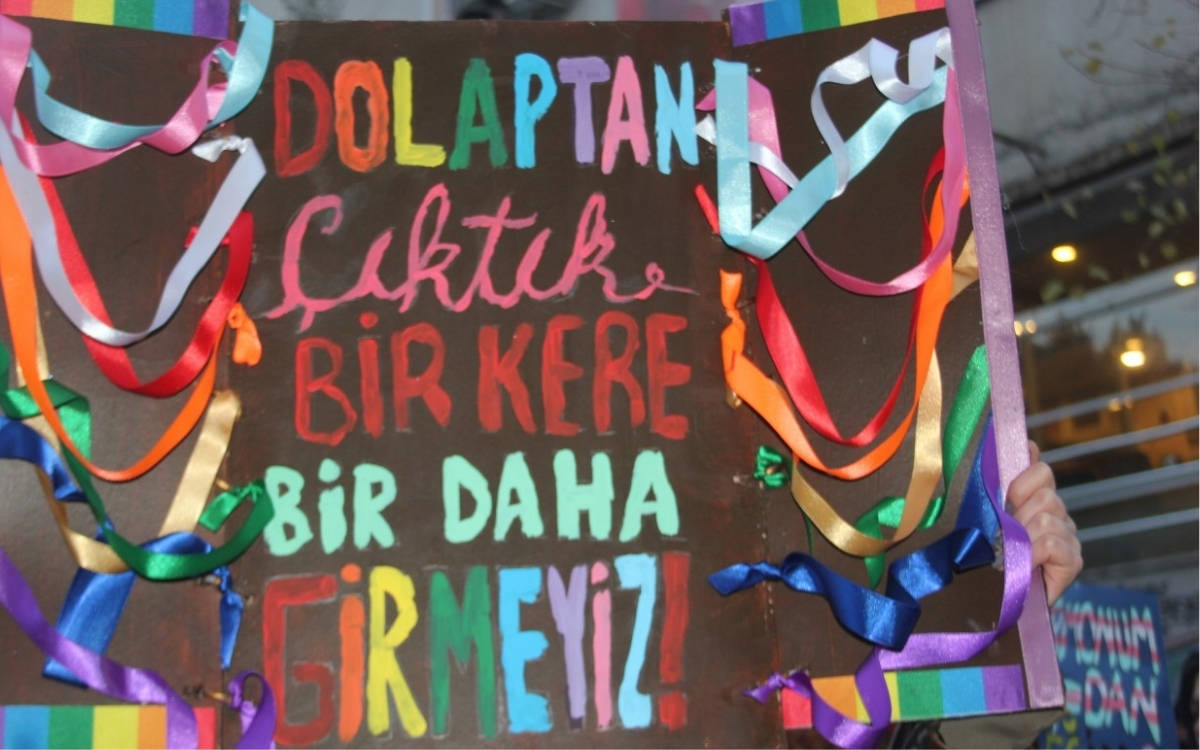

The first of Çelik’s arrests would come later during İstanbul Pride in June where they were detained along with about 50 others.

This was followed by arrests at the Munzur Culture and Nature Festival for their alleged presence at a Nisan Publishing bookstand and then their final detainment on October 14, 2025, apparently for missing their hearing for the Munzur festival incident. However, the hearing was scheduled for days after the actual arrest date. Despite this, eight officers wielding long-range weaponry took Çelik at a Dersim bus station, interrogated them for several hours and offered agent status in exchange for the names of activists. They declined.

Çelik is currently free on the condition of no arrests over the next five years. If detained, they could be imprisoned for over 10 months on previous charges.

The state of journalism in Turkey remains under threat beyond Çelik’s experiences alone though.

'Very few voices are left in the field'

As in most countries, the dying field struggles with layoffs, unlivable wages and long hours. Newsrooms are stretched thin, often meaning many important stories remain uncovered. All of these conditions are exacerbated in Turkey, due to the struggling economy and increasing threats to press freedoms that often take the form of arbitrary detention, blocked content and laws regulating speech. It’s even more challenging for independent journalists like Çelik who focus specifically on minority communities.

The impact of the work does not go unnoticed though. Many queer organizations and individuals specifically reach out to Çelik because of their positive reputation. This sense of obligation drives them.

"There are very few voices in the field following up on news about LGBTI+ issues. So if even one of them stops, it risks silencing queer voices," said Çelik. "That’s where the sense of responsibility comes from. If there weren’t so few voices I’d like to simply work at a cafe."

Although the fight for human rights is continuous and never ending, especially for those personally impacted by it, Çelik does not plan on stopping even if that means risking their fourth arrest.

“They can criminalize our work, but we will always remain with the people,” said Çelik. “As people within the free media, we will always continue to report with the ideas that we believe in … Free media cannot be silenced.” (İK/VK)