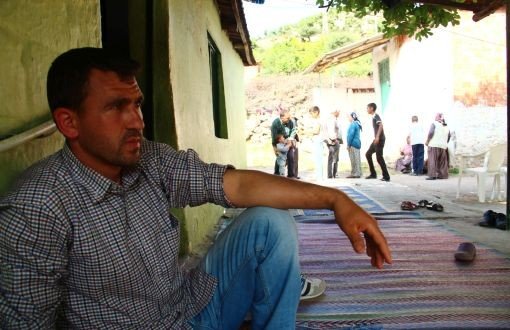

Sezai Yıldırım springs to his feet from where he was sitting cross-legged to greet us, and others who came to pay their condolences. But he has postponed his anguish. Because he too is a mineworker and he wants to tell his story, to tell everyone about the conditions in the mine.

He is 37-years-old and has two kids. We are sitting in the patio of his precarious house. “Our life consists of these mountains,” he says, looking at the endless green mountains.

His wife isn’t home; he lost two brothers. His father is inside, lying down, ill. His mother is busy greeting visitors come to pay their sympathies.

The workers who died in the Soma mine are all from the same villages. Because the company places workers from the same village in the same shifts in order to cut costs. This means that some houses have two funerals; father and son, or two brothers.

Elmadere, an Alevi village in Kınık County is one of these villages. This place is a little green village amid pine trees, just like the rest of Soma. There is still the hustle bustle of condolence visits. A lot of people come and go, excepting high government officials.

Every house in the village that lost 11 of its inhabitants has grief. The Yıldırım family is one of them. Sezai Yıldırım lost 7 of his loved ones, including 2 brothers.

One of his brothers was 29, the other 27. Sami and İlkay were their names, and the elder had 2 children.

Sezai Yıldırım works in Atabacalar, one of the other four mines of Soma Coal where his brothers passed away.

He was the first to go into the mine nine years ago because he was eldest, and his two brothers followed.

From now on he has to take care of his mother, father, wife, two children, brother’s wife and their two kids: nine people in total.

As we talk with Sezai Yıldırım, he gets angry with visitors when they say, “It’s all in God’s will.”

One of his friends phones him in the meantime. When will the mine open, when are we going to begin, he asks in a flurry. Yıldırım replies with, “I’m out.” He is somewhat angry as he hangs up. “See, there the workers are worrying about the mine while I’m here thinking about my brothers.”

Sezai Yıldırım recounted his work life to bianet.

How did your family get by before the mine?

Tobacco. We used to plant tobacco in the small field you see right across. The government first applied a quota and then gave it to a private company. We didn’t use to have much money before, but we had peace. Ultimately, when tobacco farming ended, having debts, expenses... Since we weren’t even insured, we went into the mine. First me, and then my brothers.

Did they give you any training?

What training? They took us in the morning, handed us the helmet and boots, and took us underground. Then they had the complete subcontracting system. Now there’s the staff sergeant system.

Three-four years ago they said they were going to offer courses at Celal Bayar University. They had hired someone to just talk about stuff, like a chat. I already know the mine better than him. They said to sign saying we received the training. It was a three-day course; they did it in a day.

Whose was the company when you first started?

The name was Balcı and the Ciner group ran it. They said a lot of people would get hurt when the field got narrower. It closed. Then Soma came.

How much do you make?

I get 1500 TL if I go 30 days. If you take time off, they cut 80 liras. And sometimes other cuts as well.

What is your duty?

I am a master-builder. I do what’s called air dismantling. You pull coal from the back, so I work at the pillar. At one pillar we work 50-60 sometimes 100 workers at a time.

How many hours do you work?

I’m on the vagrant shift, between midnight and 8 in the morning. I leave the house at 10 and reach the mine at 11. No one inquires about what time you go in; go in whenever you want. But there is great pressure when coming out. If you leave five minutes early, you lose the day’s salary. It also takes around 50 minutes for you to go up, on foot, and tired after your shift. But the company has the shuttle wait until the end. So long as you work. Sometimes we don’t have time to take a bath. If we call it a bath, that is. So I don’t actually work 8 hours, I work 12 when you include the time on the road.

What about lunch?

We bring our own. Cheese, tomatoes, whatever we have. Lunchtime appears to be 40 minutes, but it’s 15. If you don’t do your work, they won’t let you eat at all. We’ve had times we didn’t eat. The sergeant says, you’re going to do five crates. If you do four, no lunch, you’re going to finish it. The boss to the sergeant and the sergeant to the worker. If the worker doesn’t do it, the boss takes away his lunch. And there’s no other break.

How much vacation time do you get?

Four days a month. There’s mandatory overtime every 15 days due to shift changes. So for instance I come home at 2, and I get up again and leave at 6 for the morning shift. You never get to rest, basically. The overtime is mandatory so they only give 20 liras extra for it. So you do this twice a month with no time for rest.

Are the working conditions better from the mine where the killings happened?

It’s even worse. The wounds on my shoulder are just from walking on the path. There’s no system, no regulation.

And inspections?

You get news of it beforehand, someone telling you they’re going to send over an engineer. They tell us too. They clean up certain parts. “The inspector’s coming.” They conduct an inspection without us seeing; I don’t understand how it works. No one thinks of having us speak too. It’s just to keep a good image.

Do you have a mask?

We have gas masks; they’re all moldy. Think about it, nine years ago, there weren’t any gas masks at all. They gave them out five years ago. Nobody really picks it up and looks at it. I’ve never opened it. I swear on the Koran. If you accidentally open it, there’s a 150 lira fine. It just hangs on my waist for show.

Why do you all go there simultaneously at shift changes?

We meet each other at the pillars. The pillar mustn’t remain unattended, production cannot falter. As soon as the other worker leaves the pillar, I take over. They won’t have five minutes go by. If you leave early, the door is there; this is a private company they say. We have no job security.

What sort of tools do you use?

A dust mask, a simple piece of cloth—They don’t give you one. You need to beg and plead to get a demand coupon from the boss. Otherwise he won’t give it to you. Even though every morning they ought to give out new ones.

They give out gloves once every 15 days. The glove breaks with one maneuver with the pickax. So I have to buy the gloves out of my own pocket. It’s a lot of money with 2 liras apiece. If you don’t believe me, go and look in the house, there I have the gloves in a pile. Every six months they give you boots. These boots get ruined even if you don’t do anything but just walk.

Has there ever been a drill?

No. We were like sheep thrown in the water. There’s no refuge chamber; the company itself admits it too. I’ve never seen one.

Do you ever talk about how you would get out if there were a fire?

We’ve never seen it. The coal is like fire sometimes. We cool it down.

Do you have a black pump too?

Yes. It’s banned everywhere; only Soma’s mines have them. In the black pump, your back is clear and your front is blocked. You go backwards closing the area in front of you as you go. The coal could collapse and our back might get closed up too. There’s no other way to go.

There are a lot of deficiencies in air dismantling for instance. They say, whichever way the coal comes out. We take the coal out without spreading rolls. Normally you place pine trees for safety; this is called a roll.

All they care about is coal, coal, coal. You know how it says safety first; well, that’s a lie. Their concern is coal, not people’s health. But God be my witness, I can’t lie about this Syrian worker business, I haven’t seen it. Nor have I seen workers under 18.

How is the subcontracting system?

Someone says, I’m the boss; I need workers. The subcontractor gathers 150 men from the villages. They don’t even go under ground. We see it every day. Someone they go under for about an hour and tell the sergeant to get this and this done. They receive money both from the company and from us per capita. Check out these executives’ bank accounts, and then ours. Can they make money through mining?

Are you going to go under ground again?

I gave my two brothers, how can I go down? If things go on in these conditions, miners will continue to die.

How do you think justice could be achieved?

These people need to receive their punishment. The nation needs to come and see. The entire company is complicit. The syndicate too is a suck up that works for the company. And on top of the company there’s the AKP government. A parliamentary representative comes and tells us we’re going to vote for AKP.

In an AKP rally?

The worker goes out to go to work. They give him a clean helmet, boots. Olives and tomatoes in bread, and 40 liras in his pocket. If I don’t go, they take his name in the car, and fires him. I haven’t had it happen to me, thank God.

What about the syndicate?

The employer asked for the syndicate 4-5 years ago. We joined the syndicate because the company wanted us to, voting without any one of us knowing anything about it. Nobody defended our rights.

There was another election at the syndicate in March. This time we deliberately didn’t vote. They fired one of my friends the same night because he wanted to oppose the syndicate.

They cut 40 liras from our monthly paycheck for the syndicate. Multiply that with 15 thousand miners. They take the money, but where are they now? Two of my brothers died; no one called or asked.

Are you going to file a complaint?

I will. I’m going to attend the hearings till the end. I lost two brothers, three brothers-in-law, and two cousins. Even if my whole house turned into gold, those souls are not coming back. Maybe his family will be able to get by with this money, but this heart will remain this way for life.

* Click here to read the article in Turkish.