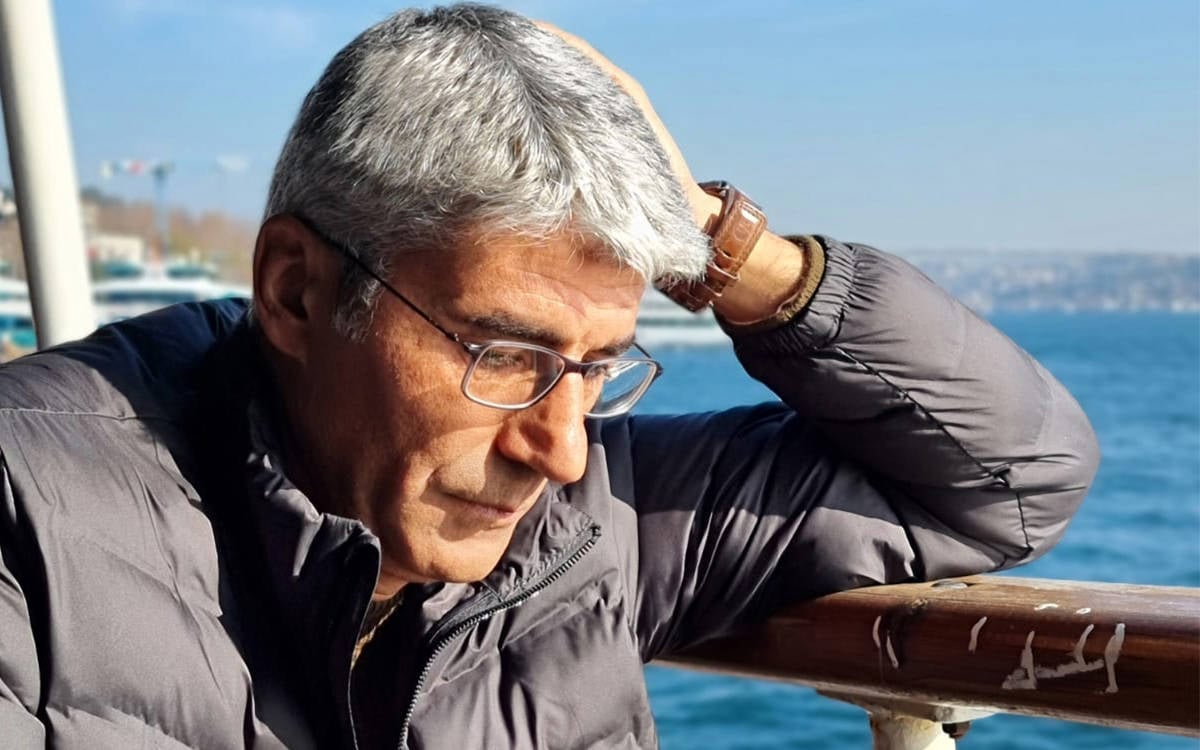

In 1994, Ilhan Sami Çomak was imprisoned at 21 years old, despite no concrete evidence against him. On Nov 26, after 30 years, 3 months, and 6 days, he regained his freedom.

We spoke with Çomak—who is deeply passionate about poetry and life, and whose words never faltered even in adversity—about his process of writing poetry, his 30 years of imprisonment, and his life journey.

Kurdish poet İlhan Sami Çomak released from prison after 30 years

'I chose poetry, and poetry chose me'

In 1994, at the age of 21, you were arrested. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has ruled on your case, and many charges against you have been dropped. You’ve published six poetry books during more than 30 years of incarceration. How did those three decades pass?

It was hard, incredibly hard—an experience I wouldn’t wish on anyone. Ultimately, in Turkey, especially for those imprisoned for political reasons, the penal system is extraordinarily unjust. It’s far removed from any sense of fairness, and we must acknowledge this. Beyond this, the conditions in prison are inherently at odds with poetry and art.

To imprison someone, particularly someone engaged in creative pursuits, means not only punishing them but also stripping them from society and the vibrant colors of life. It’s not just the individual who is penalized—what they could contribute to society is also stifled. It’s like discarding a potential piece of great art alongside the person. I’ve seen and experienced this myself over the past 30 years.

At the same time, I’m aware that my 30 years were spent in prison, but had I not been incarcerated, this many people wouldn’t be speaking to me as a poet today—especially not as a Kurdish poet. In the eyes of the state, I am a “criminal Kurd,” while in your eyes, I am a Kurdish poet. If I were given the choice between “poetry or life,” I would have chosen life. My poetry is, to some extent, a product of my circumstances.

I always had the desire and ability to write poetry, but it was these conditions that turned me into a poet. In those circumstances, the best and most truthful words could only come through poetry. So I chose poetry, and poetry chose me. I believe I’ve responded to it with justice. I’ve made a very, very small contribution to poetry, but even so, I’ve lit a spark, showing that people in prison can still engage in creative endeavors.

'I clung to the life I was torn from through poetry'

How did you first start writing poetry? Can you describe the relationship you developed with poetry?

I was in prison, and once my sentence was finalized, it became clear I’d be spending a long time there. Prison life, as you can imagine, has a monotonous and unappealing nature. That monotony was entirely foreign to my personality. I was not someone accustomed to such dullness in life.

It was at this point that poetry entered my life. Against the monotonous, repetitive structure of prison, I sought refuge in poetry. In prison, the concept of time dissolves. There’s no change, no color, no greenery.

Yet everything that prison lacked, poetry contained. Poetry encapsulated everything we know about life. Writing poetry became my way of reaching out to life, a way to search for beauty—things I had known but had been torn away from. I clung to that lost life through poetry.

At first, this wasn’t a conscious or deliberate effort. I had no one around to suggest reading poetry. But I knew that this darkness could only be overcome through poetry, so I tried. I failed. I tried again and failed again. Until one day, I realized that the things I had been writing were “poetry-like.”

'What makes me write poetry is the essence of a good poem itself'

What challenges did you face while writing and reading poetry? Did you struggle to find books? Who were you able to read? Were there any poets or writers who inspired you?

Although I was imprisoned during a difficult time, when I first began writing poetry, we didn’t face severe shortages of books. This was before the era of F-type prisons, so while resources were limited, they weren’t as restricted as they are today. We could access books, but we didn’t have the opportunity to read magazines. For example, I haven’t read magazines for many years. I used to write for magazines, but I had no way of reaching or reading them.

During that time, I did most of my initial reading in prison. I sought out poems that resonated with me or reflected the style I wanted to write. I found what I was looking for in the works of Second New poets—Edip Cansever, İlhan Berk, Turgut Uyar, Cemal Süreya.

But I must say this clearly: what fundamentally drives me to write poetry is the essence of a good poem itself. The more I read poetry, the more poets I discovered. Instead of listing names one by one, I want to emphasize that I owe a debt to many poets.

'It was like rain, like sunlight...'

Articles have been written about you, your books have been translated into multiple languages, and you’ve received awards in various countries. How did all this make you feel?

Ultimately, what frightens a person more than death? It’s being forgotten. Someone in prison fears being forgotten, fears that their voice won’t be heard.

People would tell me during visitations, “Your books are being read,” “They’re being translated into different languages.” Of course, I could only imagine what that looked like in reality. But knowing this gave me immense strength.

In that darkness, I created a garden out of words—it was all I could do. Knowing that this garden reached others meant more to me than tending to it. It was like rain, like sunlight.

'Learning to walk again, like being reborn'

After 30 years, you are physically free. How do you feel?

When people are released from prison, or about to be, they’re often told things like, “You’ll see negative things,” or “You won’t be able to adjust to life.” I heard these warnings many times. Of course, the world has changed, people have changed—it’s the natural course of life. After 30 years, I feel like a newborn, learning to walk again.

But what I’ve encountered is a pure, beautiful attitude from people. I’ve seen sincerity, people genuinely sharing their emotions with me. This is a wonderful thing for me. Contrary to all the negative things I was told, the warmth I’ve encountered gives me strength.

So, I’m doing well. I also find strength in the people and poetry that encourage me to embrace life. The best thing one can do is to share genuine feelings, and the more I see these feelings expressed, the more I approach life with love. As I sense the emotions of those who understand poetry and pour their hearts into it, my own sincerity grows. This, in turn, supports me as I take these first uncertain steps into life after 30 years.

'Writing and creating will remain the focus of my life'

What’s next for you?

I have new projects in mind, of course. Recently, I collaborated with poets from around the world, exchanging poems. They wrote poetry for me, and I wrote poetry for them. Soon, my books will be published in several countries, including the UK, the US, Norway, and France, in various languages. This means a great deal to me.

I present myself to the world as a poet, as a writer. This is an identity I cherish deeply and will continue to uphold. From now on, poetry, literature, writing, and creating will remain at the center of my life. I can’t imagine anything else.

I’ve spent 30 years imagining what it would mean to be a free poet, and I will die as a poet. Ultimately, if poetry is a profession, it is the only one I want to pursue, the only one I want to claim as mine. I intend to carry this value with me for the rest of my life.

(ED/VC/VK)