The introduction of elective Kurdish and Circassian language courses into school curricula as part of the incumbent Justice and Development Party's (AKP) plans to reform Turkey's education system has seemingly failed to stir much enthusiasm among students and parents. Critics, however, note that a boycott initiated by the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP,) the regulations governing the provision of elective native language courses and the policies of school administrations constitute the reasons why demand for these classes have turned out to be so low.

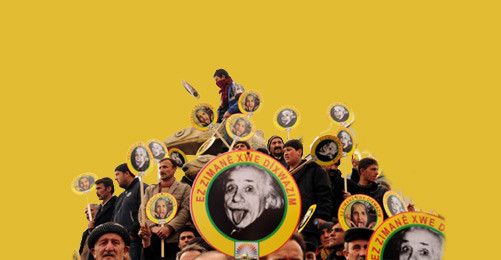

"We reject the introduction of elective [language] courses and insist on [providing complete] education in people's native languages instead. We are tired of begging," said Altan Tan, a BDP deputy from the southeastern province of Diyarbakır, adding that all Kurdish parties and organizations had been boycotting the provision of elective courses from the start.

It is therefore natural for demand for these courses to be so low, deputy Tan said.

"Schools steering students toward religion courses"

The Education Ministry announced that Kurdish language courses had come in fourth place among the list of elective courses preferred by the students and their parents in eastern and southeastern Turkey, including even in the Kurdish stronghold of Diyarbakır, following the ratification of the government's so-called "4+4+4" education reform bill which introduced a three tier schooling system, with each tier corresponding to four years of education.

While definitive figures are yet to emerge, Friday was the last day willing students were allowed to register for elective courses. Course demand for the Circassians' Adygea and Abkhazian languages also turned out to be scant, according to reports.

The controversial elective religion course entitled "The Life of His Majesty Muhammad" drew the largest number of students, while the "Qur'an," another religion course, and "Applied Maths" came in second place.

The apparent popularity of elective religion courses, however, are partly to be blamed on school administrations' "repressive and soliticing attitudes," according to Mustafa Ecevit, the organization secretary of Turkey's Education and Science Workers' Union (Eğitim-Sen.)

"Religion courses were prepared for by increasing the number of available teachers through the years. If a student wished to take the "media literacy" course, there are no available teachers for them. School administrations then tell [the students and their parents] that they can only open religion classes and solicit them to take these courses to avoid trouble," Ecevit said.

"The moment students select [a course,] the school administration is obliged to find an appropriate instructor. The administrations' soliciting attitudes also bring about pressure [on the students and parents.] The parents are then unable to resist for long, as their children are set to study in those schools for four years. They do not want to cross the school administrations. Moreover, there is also pressure coming from the neighborhood. In other words, [they] have rendered elective courses 'mandatory,' just as we had been explaining from the start," he added.

Regulations also stipulate that at least ten fifth grade students have to register for Circassian language courses for these classes to be offered in the first place. Such measures inevitably lead to the current situation, Vacit Kadıoğlu, the head of the Caucasus Associations Federation, also noted.

Only three or four schools in the eastern province of Maraş and the central province of Kayseri will now open Circassian language courses, Kadıoğlu added. (NV/HK)