In Homer’s Iliad, Mount Ida, which is now called Kazdağı or Kazdağları (Kaz Mountains), is the most important mountain of the Troas region.

Described as the mountain with a thousand springs or as “rich in springs” and “abundant in sources,” Ida has great significance for the region in terms of water supply.[1]

However, the water resources of Çanakkale, which includes a large part of the area now referred to as Kaz Mountains, have for some time been facing an increasing threat from mining activities.

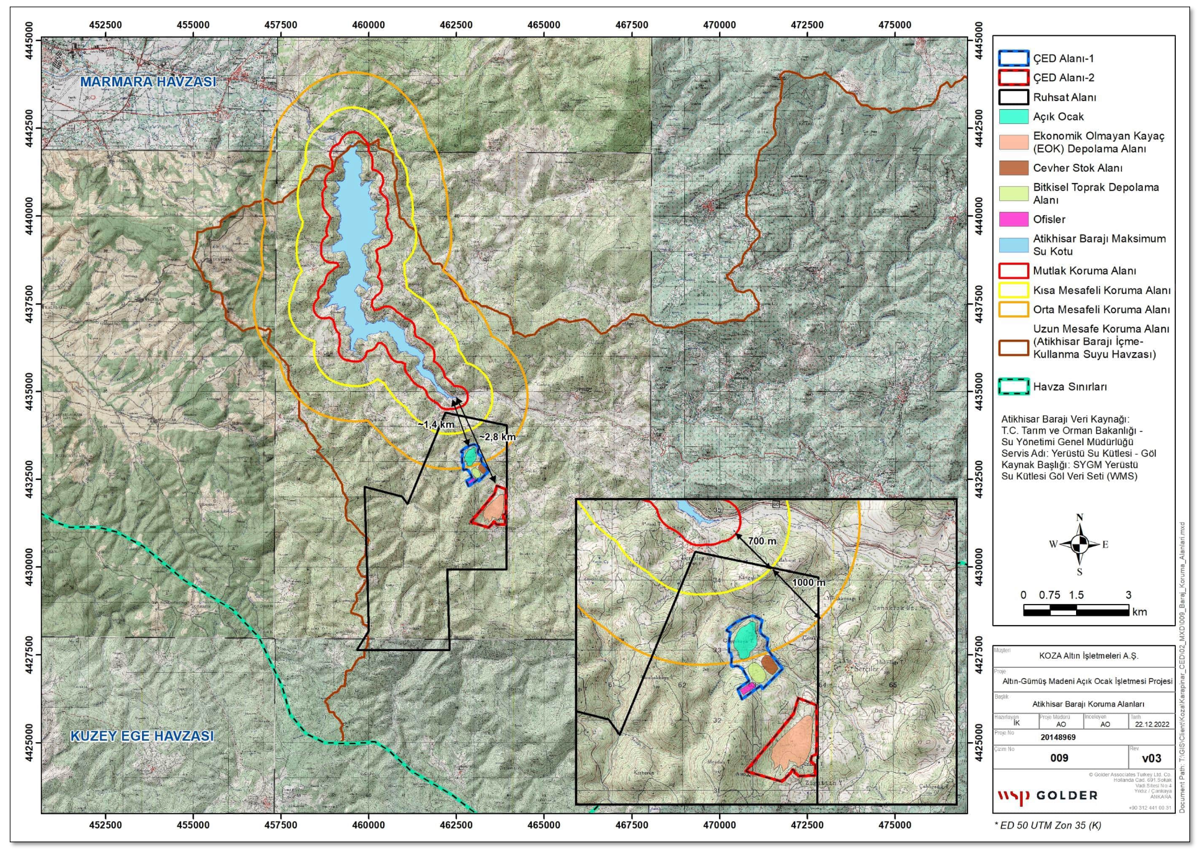

In particular, the proximity of two planned gold mining projects to the Atikhisar Dam, the city’s sole source of drinking and utility water, is causing serious concern in the region. This concern is accompanied by the local community’s and institutions’ persistent determination to resist.

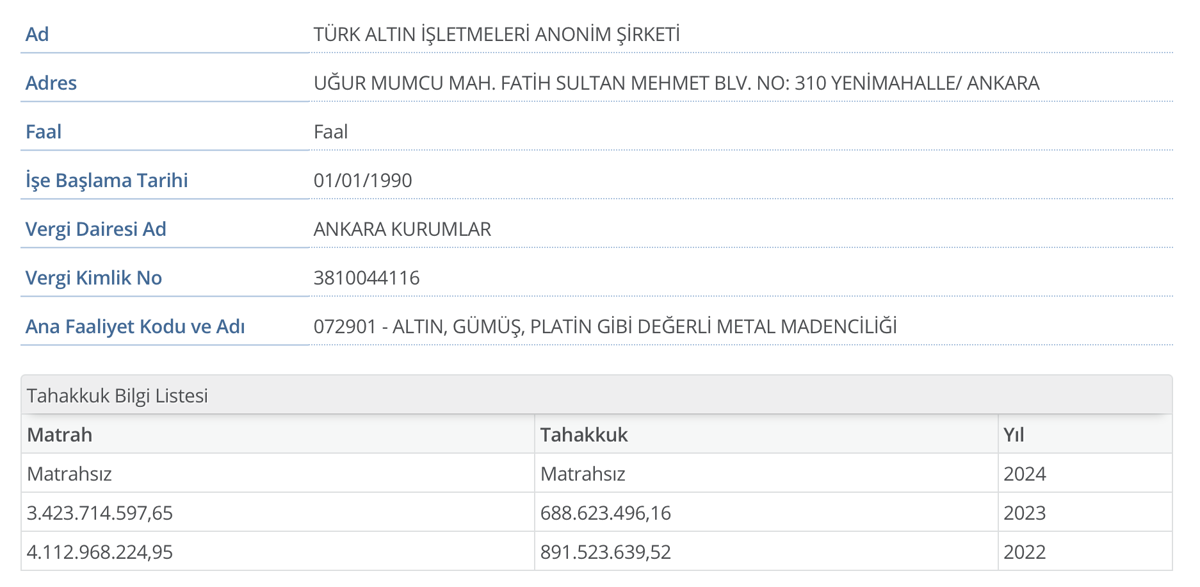

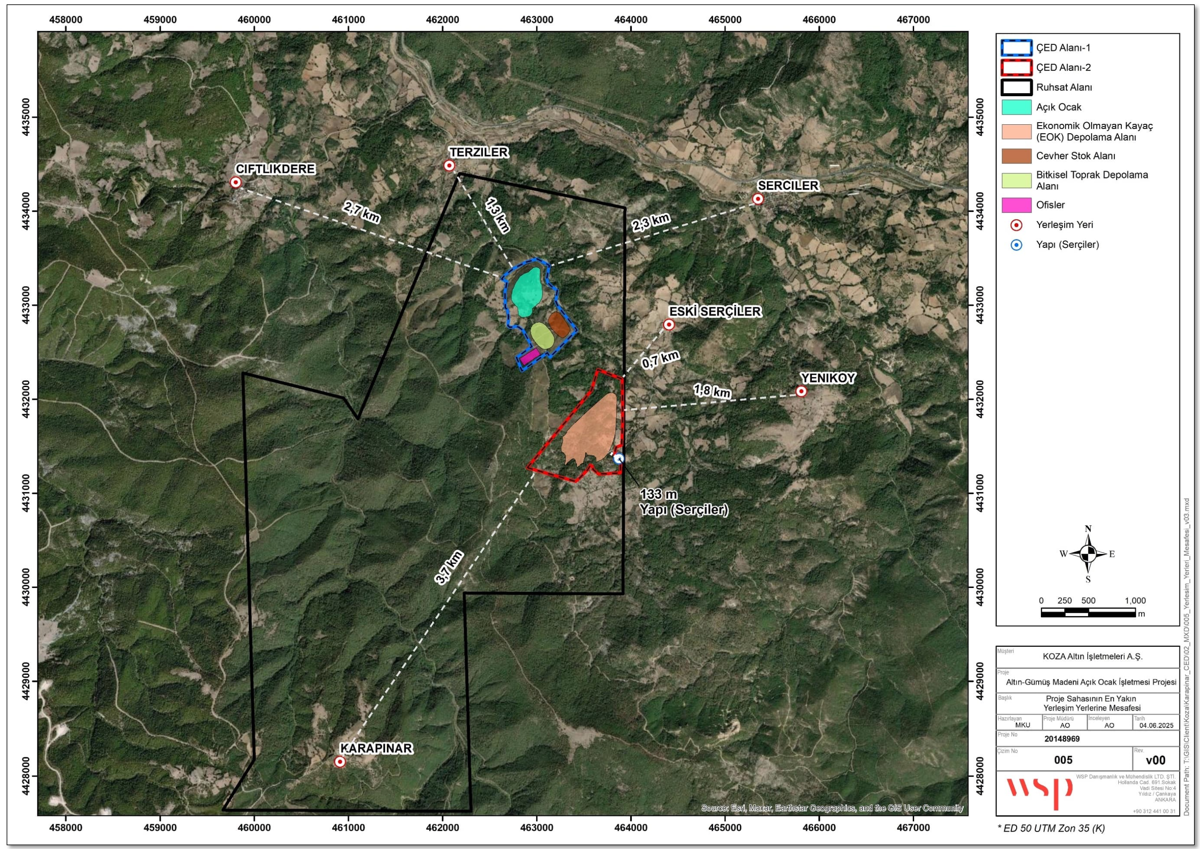

The first of these projects is the Kirazlı Gold Mine, which came to national attention in 2019. The second is a gold-silver mining operation intended to be launched by Koza Altın İşletmeleri A.Ş. (now renamed Türk Altın İşletmeleri A.Ş.) in the Karapınar area of central Çanakkale, between the villages of Serçiler and Terziler, just 1.4 km from the Atikhisar Dam. After the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) Report for this project was approved by the Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change Ministry on 17.09.2025, various legal actions were initiated by institutions such as the Çanakkale Municipality, the Chamber of Agricultural Engineers, and members of the Kaz Mountains Ecology Platform. In the days ahead, the court rulings will be decisive for the course of the process.

Issues highlighted in the EIA report

According to the EIA report approved by the ministry, the project area lies within land classified as agricultural and forested. Furthermore, it falls within the “medium and long-range protection zone” defined by Articles 11 and 12 of the Regulation on the Protection of Drinking and Utility Water Basins, published in the Official Gazette dated 28.10.2017 and numbered 30224. In other words, due to its location, this project poses a threat to the sources feeding Atikhisar, which provides life to the region through 38.7% irrigation, 50.7% flood control, and 10.6% drinking water use.

Also, according to the EIA report, no ore enrichment processes are planned to be conducted in the region as part of the project. However, it is stated that 2,700,000 tons of the total 3,221,711 tons of run-of-mine ore to be extracted using open-pit mining methods will be transported to the enrichment facility at the Kaymaz Gold and Silver Mine, operated by Koza near the Kaymaz neighborhood of Sivrihisar district in Eskişehir. The remaining ore (521,711 tons) will be temporarily stored in the ore stock area and then transported to Koza’s Ovacık Gold Mine in the Bergama district of İzmir.

According to the quantities stated here, the transportation of the ore to Eskişehir alone means carrying it from Çanakkale to Eskişehir every day for 26 months using 149 trucks, each with a capacity of 23 tons. This means the project poses additional risks both for the provinces along the route and for Kaymaz and Ovacık.

Süheyla Doğan: Water resources are in danger

Süheyla Doğan, Chair of the Board of the Association for the Protection of Natural and Cultural Assets of Kazdağı, makes important warnings about two issues while evaluating the EIA report.

“Even if there are no accidents or disasters, mines threaten water resources due to their normal operations,” says Doğan.

“There are two main reasons for this. The first is the pressure mining places on water resources, and the second is pollution. On the first point, mining consumes much more water compared to normal urban use. At the same time, it disrupts the aquifer structures of underground water starting from the drilling phase and causes displacements. Moreover, these projects are mostly carried out in forested areas. Destroying forests for mining means the disappearance of water catchment basins that feed underground water. When they start digging and opening pits, the topography is damaged, and the region’s water systems are harmed in their entirety.

“The second point is that mines inevitably pollute water resources during their normal operations—starting even from the drilling phase. The chemicals used at this stage mix with groundwater and become visible in nearby surface water bodies. Many examples of this have occurred in the Kazdağları region. Not only during drilling, but also during the normal operation of the mine, chemical pollution cannot be prevented. Any leakage from the waste reservoirs directly affects groundwater, while the threat of evaporation introduces the risk of these pollutants falling to the surface with precipitation and contaminating soil and water.”

'A tactic that may aim to accelerate the approval of the EIA decision'

“The same risks apply to waste rock piles containing heavy metals that emerge during mining. When these come into contact with air and water, they result in intense pollution, such as acid mine drainage. The open-pit mining approach to be implemented in Koza’s project often causes the area to turn into an acid lake after mining activities are completed. In a place like Çanakkale, where the risk of drought is high, such a project right next to the city’s only water-supplying dam poses a major threat. Even just from the perspective of water resources alone, this project must be opposed.

“The second noteworthy point in the EIA is that although Koza claims it will not carry out cyanide-based ore enrichment here and will instead transport the ore to Eskişehir Kaymaz and İzmir Bergama, it is very likely that we may encounter a different situation if the operation begins. Because transport costs are very high, and companies typically proceed through a three-step process. First, they apply for an area smaller than 25 hectares in order to obtain a 'No EIA Required' decision. Then, they apply for a capacity increase to expand the existing site. These two applications are often followed by a third one, which includes the ore enrichment facility and a waste reservoir. If they state at the beginning that enrichment will also be done on-site, then much more comprehensive EIA reports need to be prepared, and local reactions to the use of cyanide may increase. Therefore, stating in the first application that ore enrichment will not occur on-site could be a tactic by the company to accelerate the approval process for the EIA decision.”

'We can stop Koza once again'

The project can actually be seen as a re-adaptation in line with the country's changing conditions and laws.

Koza Altın is not unfamiliar with the region. The company already obtained a positive EIA decision in 2017 for the area where the current EIA site is located. However, this decision was annulled through a timely intervention and legal struggle led by Ekrem Akgül and the İda Solidarity Association.

Akgül explains the process as follows:

“In 2019, while we were in the field to protect Kirazlı, we discovered that Koza Altın had started mining activities near the villages of Serçiler and Terziler in central Çanakkale. Upon further investigation, we found that a positive EIA decision for this project had been obtained in 2017, but the information and documents related to this decision were not publicly accessible through digital platforms. I filed an individual lawsuit that also included a request for access to information. Then, the İda Solidarity Association, where I was serving as chair at the time, and other individuals and institutions joined the case. The court requested an on-site inspection and expert report. The report prepared by experts was strongly in our favor. But it did not stop there—an additional report was also requested. With the preparation of this supplementary report that demonstrated the damage of the project, the path was cleared for the annulment decision.

“In 2021, the court annulled the ministry’s positive EIA decision and blocked the project. However, in the years that followed, Koza Altın did not remain idle. In addition to the initial 50-hectare application, the company applied for another 65-hectare area. Now, there is an application covering 116 hectares. The inspection and expert reports are clear. There is no public benefit to implementing the project, and it will cause significant environmental harm. We are once again ready to fight alongside the local population to have the positive EIA decision annulled. Just as we stopped Kirazlı, just as we previously stopped Koza, we can do it again.”

Legal struggle

Local environmental defenders, solidarity networks, civil society organizations, professional chambers, and local governments are not only voicing their objections to the ministry’s positive EIA decision in public forums but are also pursuing legal action to stop the project despite all the administrative and financial obstacles they face.

Ali Aydın Çalıdağ, Chair of the Environmental and Urban Law Commission of the Çanakkale Bar Association, comments on the lawsuits and the legal dimension of the struggle as follows:

“The EIA report is detached from reality and full of wishful thinking. A fair outcome from the lawsuits should certainly lead to the annulment of the positive EIA decision. Since that time, the environmental impact of the project has not decreased, and the effects of the climate crisis have become even more evident. We are now living with an increasing risk of drought. In such a situation, a project that threatens the only dam of a city cannot be said to have any public benefit.

“The first lawsuit for the annulment of the positive EIA decision was filed by the Çanakkale Municipality on Oct 13. Citizens living in Çanakkale can also join this case with the voluntary support of the Bar Association. However, one does not need to live in Çanakkale’s central district, where the project is located, to be involved in the legal struggle. Nor is the municipality’s lawsuit the only one filed. The Chamber of Agricultural Engineers, the Kazdağları Ecology Platform, and citizens and affiliated groups from Çanakkale, Balıkesir, and İzmir have also filed lawsuits.

“We also know that lawsuits have been filed in Eskişehir, where the ore will be transported. Moreover, scientific studies show that underground water flows from Kazdağları can reach as far as Lesbos. In this case, even someone living in Lesbos could potentially be harmed by the project. We are talking about such a broad area of impact. Therefore, anyone from this region can become involved in the lawsuit. These lawsuits are truly filed under extremely difficult conditions. Especially in recent years, the increasing costs have become barriers to access to justice. For this reason, supporting the lawsuits that are filed is of great importance.”

Current status of Koza Altın İşletmeleri A.Ş. and its transfer to the Wealth Fund

According to its 2025 activity report, although the company produced 100,000 ounces of gold in 2024, tax records show that it closed the year with zero taxable income and therefore did not pay corporate tax.

Despite years of public debate and opposition efforts, Koza Altın is currently the owner of Turkey’s first gold mine, Bergama Ovacık—operational since 2001—as well as gold mining projects and operations in cities such as Kayseri, Gümüşhane, Eskişehir, and Ağrı. The company’s management was transferred to a trustee panel in 2015 due to alleged ties to the “Gülen Movement” and then to the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (TMSF) in 2016.

In 2023, it was decided that while protecting the rights of the company’s investors listed on Borsa İstanbul (BIST), the shares held by real persons other than these investors would be registered in the name of the Treasury.

Thirty percent of the company’s shares are publicly traded. While the main shareholder-subsidiary structures were preserved, the remaining shares held by the Treasury were transferred to the Turkey Wealth Fund through Presidential Decree No. 8857 dated 2024.

Today, the company is part of the Turkey Wealth Fund portfolio.

The ‘predatory’ mining mobilization in the Kazdağları region and across Turkey

It is clear that Koza’s Karapınar Gold Mine project near the villages of Serçiler and Terziler, or the Kirazlı Gold Mine project—halted in 2019 after major public resistance and later taken over by TÜMAD Madencilik Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş.—cannot be considered as isolated cases.

These projects can be viewed from a broader perspective as manifestations of an extractivist state policy aimed at exploiting natural assets for profit without considering their social or ecological value.

As of 2024, a total of 14,276 mining licenses covering both operational and exploration activities were in effect across Turkey. This is not a fixed number. License numbers vary each year through the tender processes carried out by the General Directorate of Mining and Petroleum Affairs (MAPEG). The areas designated as mining zones and awaiting tender cover extensive land.

As part of a study conducted in 2022, the TEMA Foundation examined the relationship between approximately 20,000 mining licenses and forests, protected areas (such as national parks and heritage sites), agricultural lands, and cultural assets across 24 provinces in Turkey. The average license coverage rate in the provinces included in the study was found to be 63%.[4]

A previous study by the foundation revealed that 79% of the Kazdağları region, which spans a broad area from Biga to the Northern Aegean, is licensed for mining.[5]

The pursuit of mining activities on such a vast scale may benefit company profitability but causes ecological destruction and poses existential risks to the regions where they are conducted.[6] The new mining law also encourages this trend.

'Turkey has virtually turned into a rose garden without thorns for miners'

In the words of Süheyla Doğan:

“The mining sector is being strongly supported. The incentives provided are enormous. On top of this, tax exemptions are granted. And if we consider that they don’t even pay for raw materials, they are making huge profits based solely on labor costs. The state does everything it can to facilitate this process.

“While support mechanisms are offered through tax regulations and incentives, Turkey has virtually turned into a rose garden without thorns for miners, especially after the passage of Law No. 7554 in parliament in recent months. Everything is in their favor. The only obstacle is us—the ones who oppose the destructive impacts of this sector. We are aware of our responsibility and will continue to resist to the best of our ability. We also invite citizens who wish to strengthen the struggle to join in solidarity.”

Footnotes:

[1] Homer, Iliad, trans. Erman Gören, Everest Publishing, İstanbul, 2024, p. 698.

[2] EIA report p. xxiii

[3] EIA report p. xxiii

[4] https://www.tema.org.tr/basin-odasi/basin-bultenleri/turkiye-maden-ruhsatlarinin-tehdidi-altinda

[5] https://cdn-tema.mncdn.com/Uploads/Cms/kaz-daglari-raporu_1_1.pdf

[6] https://bianet.org/haber/ilic-ilk-degil-akp-doneminde-en-az-2050-madenci-yasamini-kaybetti-292330

(BB/TY)