It has been four years since the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan on Aug 15, 2021.

Since that day, women’s and children’s rights have been curtailed, and, so to speak, the lands and homes they were born into have turned into hell.

Women have been banned from receiving education at the university and high school levels. Women and children in Afghanistan have been forced to live under countless restrictions like these.

The International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant for the Taliban on the grounds of “gender-based persecution.”

Özlem Altıok, a volunteer with the Women for Equality Platform (EŞİK) and an associate professor at the University of North Texas, assessed the latest developments in Afghanistan—particularly concerning women and children—for bianet on the fourth anniversary of the Taliban’s occupation of Afghanistan.

What long-term crises could the exclusion of women from nursing and midwifery training cause for maternal and child health?

The Taliban, which returned to power on August 15, 2021, has a very long list of bans it imposes on the people of Afghanistan. Most of these bans directly restrict women’s rights. The gender apartheid system that the Taliban established in Afghanistan has erased women and girls from public life and turned their lives into hell. Last year, in our interview, I explained the meaning of and efforts to keep on the public agenda gender apartheid—efforts by women’s organizations, feminist jurists, and UN human rights rapporteurs internationally, and by the Women’s Platform for Equality (EŞİK) in Turkey.

Afghanistan is among the countries with the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. Serious problems in women’s access to healthcare—especially maternal and child health—have always existed. But with the Taliban banning women from nursing and midwifery training, these problems have deepened and worsened. Today, in Afghanistan, a woman dies every two hours from pregnancy-related complications. The UN estimates that Afghanistan needs at least 18,000 additional midwives to meet basic maternal care needs. With the Taliban banning women from medical, nursing, and midwifery education, it is obvious that this need cannot be met.

According to former Afghan Health Minister Wahid Majrooh whose brief article was published in The Lancet this year, “In 2001, the maternal mortality ratio was 1,600 deaths per 100,000 live births; by 2021, it had dropped to 638 deaths per 100,000 live births.” The contributions of women healthcare workers—especially midwives—to this improvement were remarkable. For example, Zahra Mirzae, head of the Afghan Midwives Association (AMA), has told of Taliban attacks on maternity clinics, pregnant women and babies killed in these attacks, and the story of her midwife colleague Maryam—who, despite everything, did not abandon the mother and baby during childbirth and burned to death because of it. Mirzae is one of the many women forced to leave Afghanistan after 2021.

The exclusion of Afghan women and girls from medicine, midwifery, and nursing education—especially when considered alongside other Taliban bans —will further restrict women’s access to basic health services, weaken their autonomy, deepen gender inequality, and worsen maternal and child health outcomes in Afghanistan.

Taliban's third year of rule in Afghanistan: How women defend their rights 'silently and secretly'

How does the ban on women working in NGOs and institutions such as the UN harm humanitarian aid processes and overall community well-being?

These bans, above all, prevent women from existing in public life and lead to economic insecurity for women, which affects both them and their families. Especially in rural and remote areas, as we see in aid organizations’ reports, there are serious problems delivering humanitarian aid to women. When it is assumed that a man provides a family’s livelihood, those who do not fit this “model”—widows, women whose husbands cannot work, unmarried women, orphaned girls, and female-headed households—face severe hardships.

How does the closure of women’s social spaces such as parks, gyms, bathhouses, and beauty salons erode collective memory and women’s solidarity?

The Taliban’s 2023 order to close beauty salons cost 60,000 women their jobs and livelihoods. In a country where people are already struggling with poverty, this means making women even poorer. It also has the effect of preventing women from talking to each other, sharing their troubles, and organizing in public spaces—something just as important as economic loss and unemployment. The Taliban’s goal here is crystal clear: to block women’s empowerment and solidarity. Because they are afraid of women. I won’t get into psychoanalysis or the role of their bigoted interpretations of religious texts to explain this fear, but in short—they are terrified of women.

Excluding women from social and political spheres

What dangers does encouraging boys to report their mothers or sisters under Taliban propaganda pose for the social values of future generations in Afghanistan?

Several important points stand out here. First, the Taliban cannot implement its bans alone and effectively. The prohibitions are so absurdly far-reaching that not only women but also the rest of society questions the regime’s legitimacy. In this situation, the Taliban makes its job easier by delegating enforcement of the bans to male family members, indirectly shifting responsibility onto others.

On the other hand, it also aims to control men who do not share the Taliban’s ideology and women who want to protect male family members from harm. This serves as a strategy that both strengthens social control and suppresses opposition. Moreover, even though they never give women a place in government or decision-making positions, they try to use women as part of the surveillance and reporting mechanism. In this way, they indirectly assign the burden of enforcing bans to women and establish social control.

These policies not only completely exclude women from social and political spheres but also deepen gender inequality and severely restrict women’s ability to exercise their own agency. The effects are devastating, especially in health and education. The Taliban’s bans go beyond restricting women’s access to basic health and education rights—they negatively impact Afghanistan’s overall social welfare and living standards. They also have a particular impact on women’s mental health. This must be emphasized. The more you read and think about the Taliban’s bans, the more maddening it is. Imagine living through it.

'Girls are being deliberately deprived of right to education'

What do you foresee as the impact of the Taliban’s ban on girls’ education beyond middle school and on women’s university education for Afghanistan’s future socio-economic structure?

Let’s imagine a girl who, on August 15, 2021, when the Taliban returned to power, was waiting for summer break to end so she could return to school after primary education. Now, this girl is 15 years old and, for four years, while her brother or neighbor might be going to school, she has been at home. She is forbidden from going out. Forbidden from going to the park. She can only help with her older sister’s or mother’s sewing, carpet weaving, or cooking work if these are run from home.

The areas where women can work and produce are generally limited to these home-based jobs. Now imagine hundreds of thousands of such girls. These girls are being deliberately deprived of the right to education and activities that foster socialization and social solidarity. This creates a serious socio-economic loss. These individuals are deprived of fundamental human rights and denied the chance to become adults who can contribute to society’s welfare.

Their creative energy, productivity, dreams, and hopes are deliberately stifled. The Taliban’s aim is for girls to marry young, have children, and live under the command of a man—preferably a Taliban fighter or supporter.

At the end, I also want to mention how what is going on in Afghanistan relates to what is happening in Turkey today.

How can underground schools led by Parasto Hakim contribute to Afghan society’s capacity for resistance in the long run? How do you interpret the impact of such activities on the sense of solidarity among women and girls?

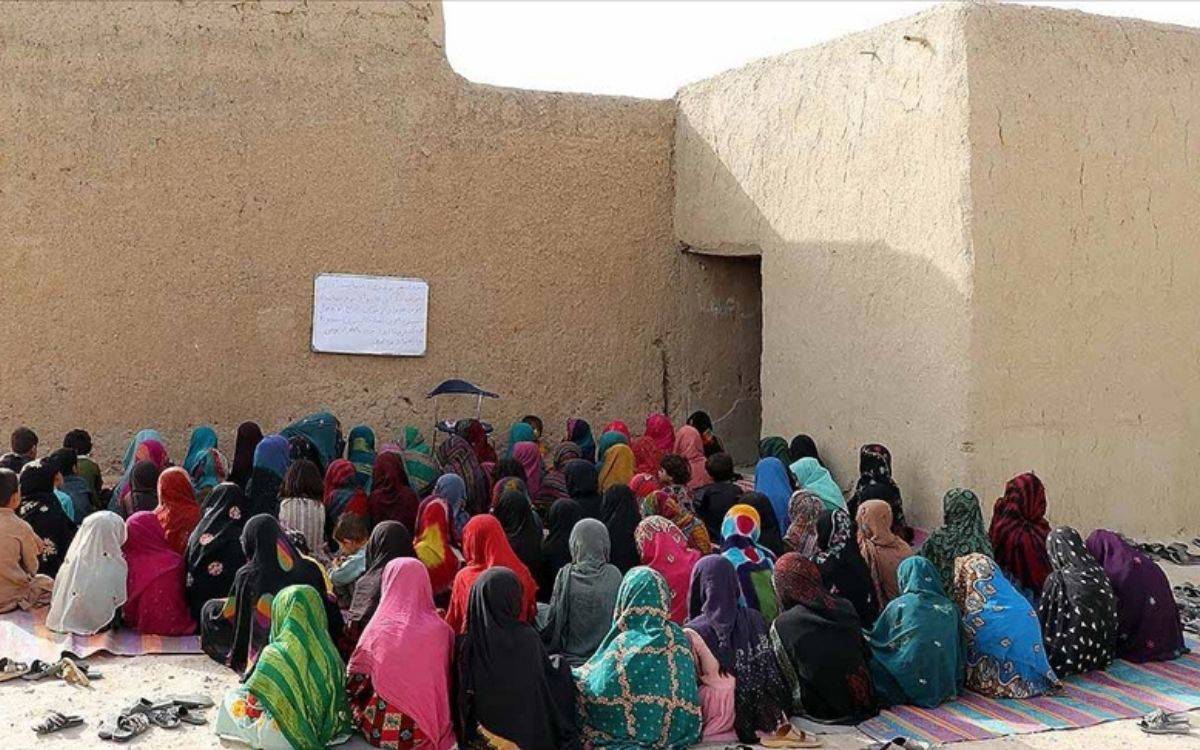

I believe there are about 15 underground schools founded under the leadership of Parasto Hakim. I am sure there are others because most women in Afghanistan do not accept being deprived of the right to education, the right to work, and freedom of movement. It doesn’t matter which country they are in—women resist, everywhere and under all manner of circumstances. The gains made in Afghanistan in education and in women’s representation in politics and the judiciary are guiding their post-2021 resistance and struggles. I am certain they will continue to do so.

Before the Taliban took power again in 2021, there were 63 women in the Afghan parliament; nine women served at the level of minister or deputy minister. Now that number is zero. Afghanistan’s judiciary had 280 female judges and more than 500 female prosecutors. Now they are gone. Nationwide, there were more than 2,000 small and medium-sized businesses owned by women, and most of them have been shut down. Thousands of women teachers who taught in schools before the Taliban are now banned from working outside the home.

But of course, these are women who know what they are capable of and who have seen that another life is possible. I think it is not surprising that they establish underground schools, teach there despite many risks, and work to give hope to girls.

What is the level of sustainability and accessibility of digital initiatives like Afghan Geeks and Vision Online University? What methods could the Taliban use to block these initiatives?

I don’t have detailed information about these two initiatives. However, I recently listened to a talk by Sara Wahedi, who describes herself as a “technologist,” and I can share something she said. She emphasized that software programs and the technological infrastructure of each country—and how they are used—are not the same. In countries in crisis, she highlighted the importance of supporting local software developers.

Since I teach at a university myself, I also want to add this: during the COVID pandemic, we learned in a rush—and because we had no other choice—how to teach remotely. But after the pandemic, we were eager to return to in-person education as soon as possible; both we and our students. Technologies that make online meetings possible are useful—and can be applied in certain courses—but I cannot imagine education being only in this format. For many reasons I won’t go into now, I believe no academic program should be conducted entirely online.

More importantly in our context, I think we must not normalize the exclusion of girls and women from education in Afghanistan, and we must expose the Taliban every month, every day, and push for these bans to be lifted. Unfortunately, this is not being done. In Turkey, there are even people who cannot stop praising the “developments” in Afghanistan!

How can women who sustain these forms of resistance be supported psychologically under current oppression? What role do you see for the international community?

As I said earlier, women who have previously worked as students, teachers, lawyers, etc., will continue to resist and will teach younger generations how to resist. Of course, there is also a darker picture created by current bans: a serious mental health crisis. There are reports of increased anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even suicide in Afghanistan.

If we are talking about the international community in terms of existing intergovernmental institutions, their inadequacy and pitiful state are starkly revealed today by the ongoing genocide in Gaza. But there are also steps that different countries, regional blocs, and perhaps institutions such as universities can take.

For example, let’s consider these underground schools. They must operate in secrecy under the shadow of repression, but could there be some form of communication and “diploma recognition” agreement between these schools and universities outside Afghanistan? Steps to build this infrastructure would provide major support to women fighting alone under oppression.

Impact of resistance movements

How can we increase the impact of these resistance movements with the support of the diaspora, civil society, and international organizations? What concrete actions do you recommend?

First, we must be aware of these resistance movements, publicize them, and tirelessly express that Afghan women do not accept the Taliban and its bans. Standing in solidarity with Afghan women in our own countries is also extremely important.

In July 2025, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants against two senior Taliban leaders for “the crime against humanity of persecution, under article 7(1)(h) of the Rome Statute, on gender grounds against girls, women and other persons non-conforming with the Taliban’s policy on gender, gender identity or expression.” However, many countries—including Turkey—continue visits, business agreements, and similar steps that legitimize the Taliban administration. Ending such activities would weaken the Taliban and strengthen resistance against it.

Looking at the Doha talks facilitated by UN officials, where, due to Taliban insistence, not a single Afghan woman was at the table, I wonder, does this not break the spirits of women resisting inside Afghanistan against all odds? There are documents like UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which call for women’s participation in peace and post-conflict reconstruction processes. However, in practice, these are always sacrificed to other “security” issues. What about women’s security?

In other words, women must be included in all decisions impacting their lives; they must be at the table.. Supporting women in Afghanistan with remote work opportunities, inviting them as students or speakers to classrooms are other concrete actions we can take. This would also make education and working life more inclusive. I say this, but on the other hand, there is currently a series of challenges facing international organizations and civil society. Under the leadership of the Trump administration—and with the open contribution of many other countries—attacks on women’s rights have directly reduced the influence of civil society organizations and international institutions working specifically on gender equality. This closing of space is an ongoing process and struggle…

How can global feminist movements make Afghan women’s solidarity and resistance more visible? What are your recommendations for international monitoring and action mechanisms?

Afghan women and feminist movements in solidarity with them are organizing a “People’s Tribunal for Afghan Women” in Madrid in early October. This tribunal will hear testimonies from Afghan women. Prosecutors, legal experts, civil society activists, and human rights defenders with expertise in international criminal law will also be heard. The tribunal will be broadcast live. We can watch this live broadcast, share it with others, and keep the issue on the agenda to continue standing in solidarity with Afghan women until we end gender apartheid for good.

In a 2022 article you wrote, you critiqued the efforts to make a new Constitution under conditions of “talibanization” in Turkey. When you look at the situation in Afghanistan alongside what is happening in Turkey today, what do you say?

What is happening today in Afghanistan (and indeed in the United States, which occupied that country for decades) clearly shows us this: women’s hard-won rights are never secure. Against attacks on equality and secularism, we must be on guard as if our lives depend on it—because they do.

Let’s look at a current news item from the “new Turkey” being pushed toward Talibanization:

This week, AKP’s Yasin Aktay—one of Erdoğan’s former advisers and now a columnist for Yeni Şafak—said, “Afghanistan is heaven on earth for those who want to go there; with its people, its nature, all the blessings God has bestowed.” To men who compare Afghanistan, which the Taliban has turned into hell for women, to paradise, one must ask: Would they want to live in that paradise themselves? At a time when the severity of the situation in Afghanistan can be clearly seen by the millions of Afghan refugees forced to migrate to neighboring countries, when in 2025 Pakistan and Iran are forcibly deporting these refugees, when human rights organizations warn of the grave consequences this will have—especially for women and girls—what does it mean to claim Afghanistan is “heaven on earth”?

As Hülya Gülbahar, a prominent feminist lawyer and Women’s Platform for Equality member observes: “To admit that women’s hell is men’s paradise is the brazen, arrogant face of patriarchy.”

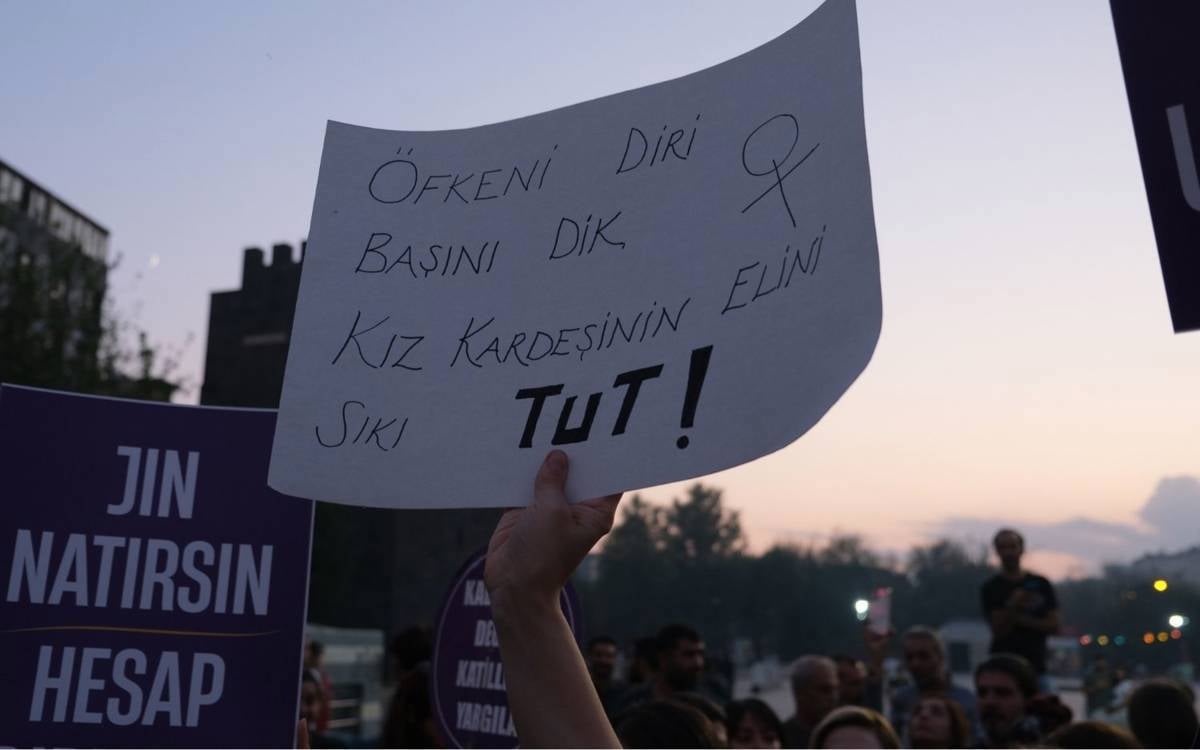

Another very current issue that highlights the seriousness of threats women face in Turkey:

Since its founding, the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) has existed precariously alongside the principle of secularism, and today it has an enormous budget that is larger than many ministries. In its sermon of August 1, 2025, the Diyanet talked about “modesty” (edep) and “decency,” (haya) telling women how to dress in public. This sermon is part of ongoing attacks on the principles of the Republic—especially equality and secularism. Although the sermon says, “The responsibilities that God places on men and women in terms of modesty and chastity are the same,” it explicitly names further responsibilities for women: “Let them not display their adornment except what is apparent thereof. Let them draw their headcovers over their chests…”

The sermon also says, “To be in public spaces, especially institutional settings, with inappropriate clothing is to challenge even the most basic moral rules. This is not modernity; it is primitiveness. Anyone who remains silent at the violation of moral and decency standards bears a great sin.” The sermon, delivered in the nearly 90,000 mosques across Turkey that Friday, attacks women’s rights and freedoms to be in public spaces in what is deemed “inappropriate” clothing.

We have spoken of the Taliban and its bans in Afghanistan. Let us not forget the theocratic regime in Iran and what they mean for women. Mahsa Amini was not detained by Iran’s “morality police” for not wearing a headscarf, but for wearing it “improperly,” and she was killed. Similar risks abound in Syria today, where Alawi women have been kidnapped, Alawis and other minorities massacred, and where all women face serious threats to their rights as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), formerly the al-Nusra front, tries to impose strict governance rooted in its interpretation of Islamic law.

In Turkey, in the case of Turkish singer-songwriter Gülşen, we saw that people can be jailed even for a joke invoking religion, a joke for which they apologize publicly. Diyanet’s sermon is, in effect, “laying down the law” to society—especially to women, in a context where it is impossible to freely discuss religious issues; Diyanet helps shape state policy and budgets; and hate campaigns are conducted with state-backed protests targeting LGBTI+ people and women’s organizations.

But women are not buying into these sermons and rhetoric, which reflect the patriarchal interpretation of a particular school (mezhep/mazhab) of a particular religion. The reaction of many women from different segments of society and political views to this sermon is proof that women will not give up their rights or the principles of equality and secularism. Aylin Nazlıaka, the Deputy Chair of CHP, the main opposition party, issued a statement that “the Diyanet’s sermon violates secularism… controlling women and declaring their style of dress ‘forbidden’ (haram) is outright oppression; it is the institutional language of sexism.” Muslim feminist writer Berrin Sönmez’s decision to remove her headscarf, saying “I reject the path the Diyanet and the government are taking—the path of oppression,” is especially important in showing that the Diyanet’s sermon has also disturbed devout women who wear headscarves. The misogynistic, reactionary backlash against Nazlıaka and Sönmez shows that supporters of the government, which has declared war on the Republic’s most fundamental principles, are not few.

Attacks on secularism are automatically attacks on the principle of equality. Because once the particular interpretation of a particular sect/school of a particular religion is prioritized, this religion/school/interpretation is considered superior to others in “public spaces” and “institutional settings.” The price for concessions from the principle of secularism is paid first—and most heavily—by women. It has always been so. That is why women do not give up on equality and secularism. They cannot. They will not.

Because equality and secularism are not only for a certain group of women, not only for those who identify as feminists, and not only for women—they are necessary for everyone, absolutely everyone. (EMK/VK)