In Mona Benyamin’s video, Tomorrow Again (2023), a two-channel broadcast platforms a pair of older men who seem to have breached senility as they state opposing testimonies, with one saying I saw everything, the other nothing, repeating themselves ad absurdum. The scene abruptly shifts to a bus security cam. The transition is as disorienting as it is deflating. Simply, something is missing, and the artist, born in Haifa in 1997, does not offer answers or solutions even as the conflict of her birthplace is platformed front and center in her darkly humorous art.

Similarly paralyzed by a deadlock of political and economic irregularities, the city of İstanbul, with its estimated 200,000 stray cats, the largest feral feline population of any major city, is a shadow of itself, as the ghost-limb of failed democracy continues to cause its body politic pain and in that way, shares regional sympathies with Israel where the territorial occupation and illegal settlement of Palestine has come to represent an amputation of national conscience.

Lebanese curator Christine Tohmé did not open the 18th İstanbul Biennial with a purr of somnolent aestheticism, but a hiss of moral indignation, echoing the global rally for Palestine as she opened Turkey’s flagship art event facing the installation of Red Navigapparate (2025), mature olive, citrus and nut trees growing from over a hundred red barrels on moveable pallets at the Former French Orphanage by Jerusalem-born, Ramallah-based artist Khalil Rabah. In a show to affirm shared regional concerns from Beirut to Edirne, Gaza to Dubai, the spatial logic of Rabah’s arboreal work imparted an ecological consciousness recognizing the strained unity of transnational, sociopolitical identities that span the geographies of the greater Middle East.

Postponed last year due to a row over advisory board decision-making that led to critiques of the institution’s Eurocentric curatorial representation and its sensitivities to artistic direction that might flaunt censorship of the Armenian Genocide, the 18th İstanbul Biennial’s titular theme of The Three-Legged Cat arrived as an excruciatingly accurate symbol of a municipality reduced to a fragmentation of its most exhausting stereotype in the wake of bald-faced public duplicity.

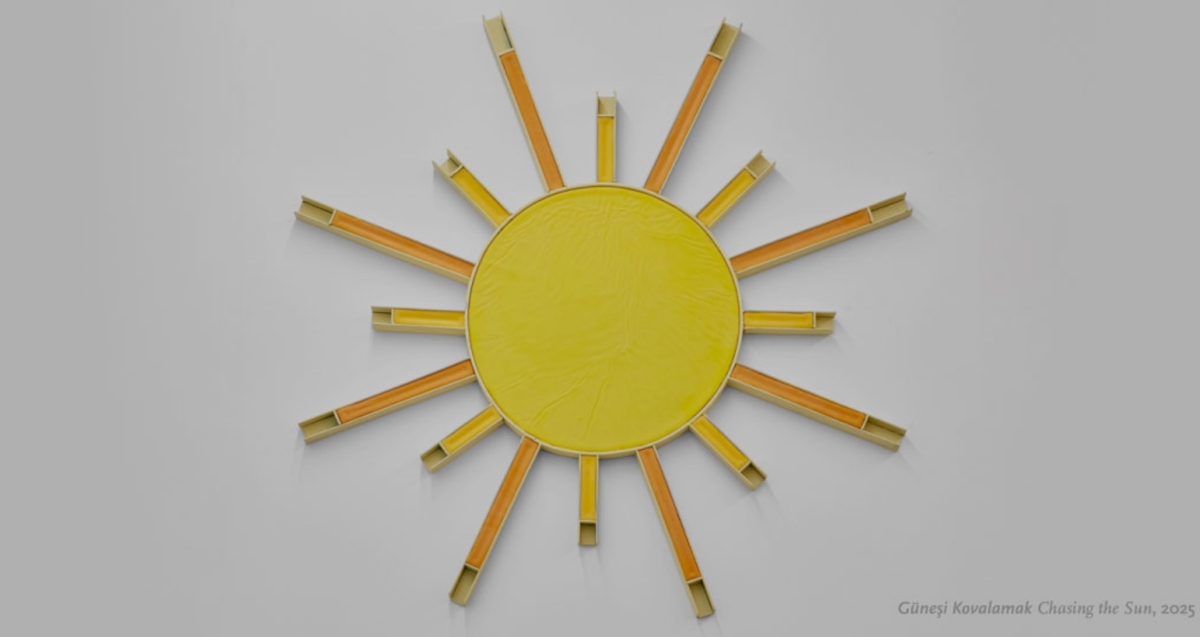

This tone of flagrantly obscurantism, the all-too-common folly of reckless diversion in the midst of deep-seated corruption, is animated with exaggerated reflexivity in the installation art of Lebanese artist Marwan Rechmaoui, whose multi-work piece, Chasing the Sun (2023–2025) carries the torch of site-specificity to critical dimensions. Analogizing the conflicts he witnessed as a child while the Lebanese Civil War raged as he came of age in the mid to late 1970s, Rechmaoui poses war as a lethal game of winners and losers.

Set to a breathtaking view of the Bosphorus that might evoke the privileged, guilty pleasures of wartime negligence, the presence of swings, an oversized, ridable wooden horse, sandboxes and hop-scotch seems, at first glance, capable of equalizing otherwise reticent adults into a vision of childlike egalitarianism. Rechmaoui has more sinister designs, as he sees in these contrivances of play the building of modes of competition that, while irrational, found the basis on which state-sanctioned murder is justified, as through inheritances of material possession and the imposition of arbitrary rules.

A short walk from Rechmaoui’s installation at the soullessly renovated, whitewashed Zihni Han overlooking the confluence of the Golden Horn into the Marmara Sea, the Biennial’s exhibitions at the Galata Greek School offer a smorgasbord of artworks in manifold forms, among them the surrealistic canvases of fellow Beirut-born, Lebanese-Armenian artist Seta Manoukian, whose paintings carry the weight of moral repugnance in discolored scenes of urban grit in which suited and overweight figures appear as shells of humanity. Les Arcades (1985) is one such work, painted the year she fled for California, an exile that her compatriot and elder peer Etel Adnan also took up in the spirit of her best-known literary work, The Arab Apocalypse.

In the following years, Manoukian would create paintings like The Dream of His Life (1993), flooded with a backdrop of blood-red hues and centering a man both upright and sideways and whose chalk-white outline resonates with the shape of one remembered in the emptiness of a line drawing.

The Biennial, for all of its maximalism, concentrated in the overpopulated heart of downtown, European İstanbul, conveys moments of focus that startlingly visualize unseen elements behind inner-workings of power that affect the global majority.

The painting, Acolytes (2024) by American artist Ian Davis is a case in point, hanging amid frenetic diaries from Gaza by Sohail Salem and an interactive film by Sara Sadik, the scene of black-suited, cult-like figures standing before a fire at the mouth of a humongous shorefront cave points to an invisible world of economic minorities whose chauvinism has been set loose on a burning planet, their presence shrouded in the smoke issuing from the unknown source of their unsettlingly ubiquitous whereabouts. (MH/VK)