Citizens and environmental organizations engaged in ecological struggles in Turkey are facing astronomical fees for expert witness assessments and site inspections when they go to court.

These costs, which have reached 94,000 liras in Gümüşhane, 180,000 liras in İzmir, and 1.5 million liras in the Marmara region, have become an almost insurmountable barrier to seeking justice (1 US dollar = 41.1 Turkish liras). For context, the minimum wage is 22,104 liras, and the average wage in the private sector is slightly higher.

The Polen Ecology collective drew attention to the issue in a social media post in May. The post noted that a court had set an expert witness fee of 94,000 liras for a lawsuit filed against a cyanide-based gold mining project planned by SSS Mining, a subsidiary of Yıldızlar Holding, in Aksu village of Gümüşhane, northeastern Turkey.

The group called for public support, stating, “These high expert witness fees in environmental lawsuits hinder the pursuit of justice. They serve to shield corporate projects from public oversight.”

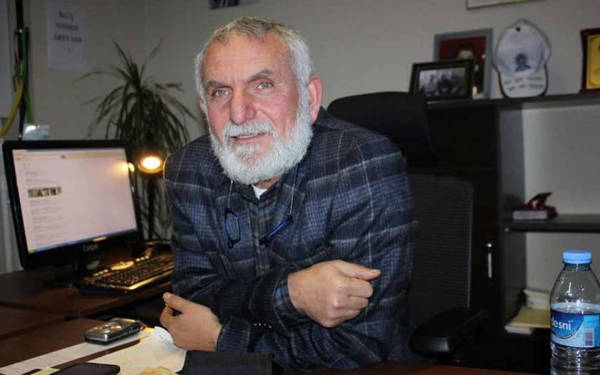

Explaining the background of the case, Cemil Aksu from Polen Ecology said, “93 percent of Gümüşhane’s surface area has been licensed for mining operations such as copper, silver, and gold. These areas include forests, agricultural lands, pastures, and residential zones. Nearly the entire territory of this small province is being opened up to mining.

"We filed a lawsuit to overturn the decision stating that an environmental impact assessment (EIA) was ‘not required’ for the mine in Aksu village. But we were faced with an astronomical expert witness fee of 94,000 liras. There was no way for the villagers to afford this. So, we issued a call for solidarity, and thanks to the contributions of concerned citizens, we managed to raise the amount.”

Aksu notes that environmental lawsuits were far more affordable just a few years ago. “In 2016, during the resistance against hydroelectric power plant projects in the Black Sea region, there was Uncle Kazım (Delal) from Rize. He sold the cow in his barn to be able to file a lawsuit and pay the expert fee. Today, even if you sold the entire village, you couldn’t cover these costs.”

According to Aksu, the costs are being deliberately increased from the outset to discourage citizens and civil society organizations from taking legal action. “Expert witness fees have become a shield that protects corporations. The biggest obstacle to citizens seeking justice is now these costs.”

1.5 million liras in expenses in Ergene

The expert witness fee demanded for the mine in Gümüşhane’s Aksu village was paid through collective solidarity. The legal battle against the mine is ongoing. Meanwhile, a similar situation is unfolding in the Marmara region in the country's northwest.

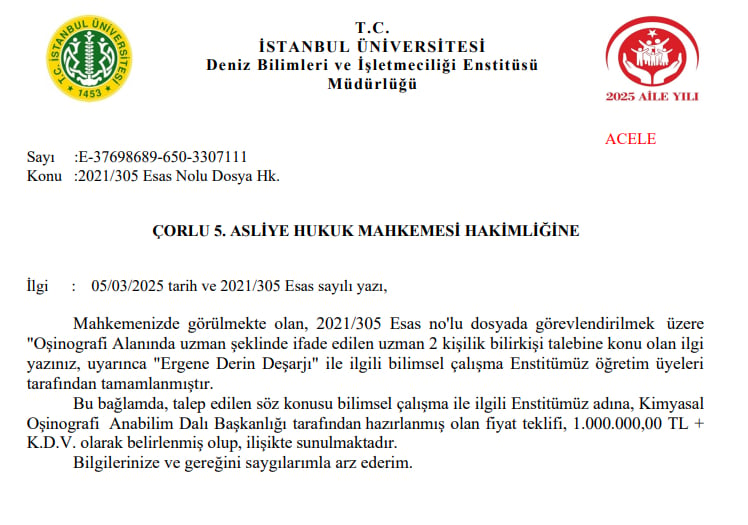

Derya Tolgay from the Let Marmara Live (Marmara Yaşasın) initiative shares the staggering figure they encountered in a lawsuit filed against Ergene Deep Sea Discharge Inc. in Tekirdağ, saying, “We were asked to pay an expert witness fee of 1.5 million liras. In our initial objection, we pointed out that the expert panel didn’t even include a hydrologist (a scientist specializing in the water cycle). The measurements were inadequate.

"We demanded comprehensive analyses to be conducted in a laboratory setting. But the fee set for this was unbelievably high. No individual or civil initiative could possibly afford such an amount.”

According to the case files, the Institute of Marine Sciences at İstanbul University submitted a bid of 1.2 million liras for the expert study, while a private company proposed 296,520 liras for the chemical analyses.

Tolgay says they have already spent 148,000 liras, but with this new demand, the total cost will exceed 1.5 million liras. Their petition to the court explains, “When it comes to the financial aspects of the proposals from İstanbul University and the chemical analysis laboratory, the proposed cost is exorbitant in relation to the scope of work. The plaintiffs cannot afford to pay these amounts.

"The plaintiffs filed this lawsuit not for any personal gain, but out of a sense of responsibility toward the environment, society, and future generations.

"At this point in the lawsuit, it is not feasible for the plaintiffs, who brought this case as an act of public responsibility, to cover the roughly 1.5 million liras in inspection, expert witness, and analysis fees.”

'We’re in a Don Quixote-like state of uncertainty'

In the most recent hearing on Jun 25, 2025, the court rejected the request for an injunction; however, the case file is still under expert review. According to Tolgay, this fight concerns not only the parties to the lawsuit but all of Marmara: “To prevent one more nail from being hammered into Marmara’s coffin, Ergene Deep Sea Discharge Inc. must immediately halt its discharge of wastewater into the sea.

"The company is not open to oversight, and other issues remain shrouded in secrecy. There is no definitive data on the volume of daily waste being dumped into the Marmara Sea. At this stage of the lawsuit, we are trapped in a Don Quixote-like struggle against windmills.

But this is not about Don Quixote’s delusions, it’s about the stark reality that a company polluting the Marmara Sea irreversibly is being shielded by high-level powers behind a veil of secrecy.

Toxic waste is flowing from Ergene into Marmara. The sea snot (mucilage) was just the most visible consequence. Our lawsuit is about defending Marmara. But with these costs, civil society is left powerless. No one can afford to file an environmental lawsuit at these prices.

When you look at the situation, there’s a company polluting the environment and causing ecological destruction. They’re profiting from this. On the other side are those trying to protect nature and prioritize the public good, and all the costs are being dumped on them. The demanded fees are outrageously high. Ultimately, in matters concerning public interest, these expenses should be covered by public funds.”

A growing political concern

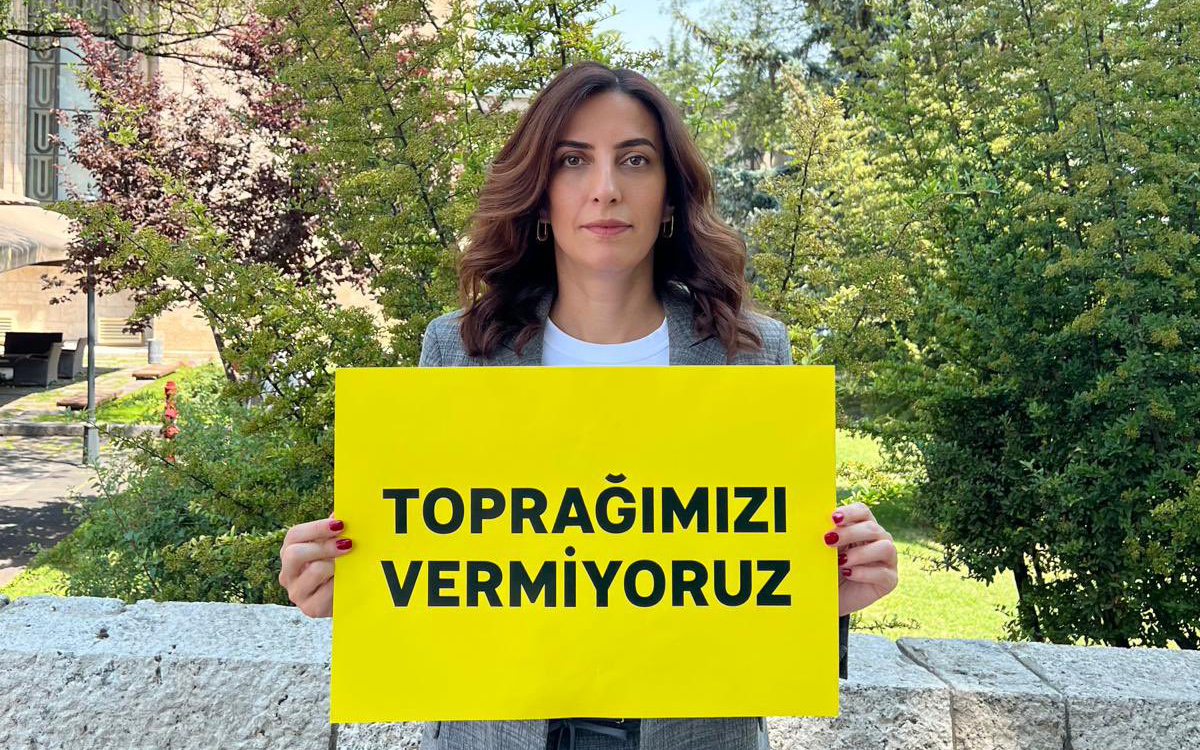

This barrier is not just a concern for environmental organizations; it has also made its way into the political agenda. Evrim Rızvanoğlu, then a DEVA member, now a CHP MP representing İstanbul, submitted a draft bill to Parliament in May 2025. The proposal seeks to ensure that “all or part of expert witness fees in lawsuits filed in the public interest to protect the environment, natural assets, natural resources, or cultural heritage be covered by the Treasury.”

The bill is currently pending in the Planning and Budget and Legal Commissions. Parliament is on recess, and the new legislative session will begin on Oct 1. It’s unclear when the bill will be brought before the General Assembly, but Rızvanoğlu continues her advocacy.

Explaining her motivation for submitting the bill, Rızvanoğlu said, “In this country, when a citizen wants to file a lawsuit to protect their environment, forest, or water, they face a massive financial wall. Costs start at 100,000 liras and can go up to 1.5 million liras. These are not amounts that a villager, a worker, or an environmental volunteer can afford.

“My concern is this: You can’t tell a citizen, ‘You may be right, but if you don’t have money, you can’t go to court.’ Environmental lawsuits aren’t filed for personal gain; they’re about our collective future. That’s why I took action to eliminate this barrier. Because this isn’t just a financial issue—it’s about whether people can actually seek justice.”

'Designed to wear people down'

Rızvanoğlu says people are being forced to drop valid lawsuits because of exorbitant expert witness fees:

“I can summarize the situation like this: It wears people down, discourages them, silences them. Citizens want to exercise their constitutional rights but are met with financial barriers.

Yet environmental lawsuits are not filed for individual interests but for the common right to a livable environment. That’s why I proposed that this burden be shifted to the Treasury. Because in lawsuits concerning the public interest, the cost should also be borne by the public.”

Rızvanoğlu’s draft law refers to Article 36 of the Constitution, which guarantees everyone the freedom to seek justice in court, and Article 56, which obligates both the state and citizens to protect the environment. She also points to a Constitutional Court (AYM) precedent: “The right to access the courts must be available not only in form but also in substance.”

“The right to a fair trial is not just about being able to submit a petition to a court. It also includes access to the evidence, expert reports, and inspection results needed to support that petition. If a citizen is told, ‘First, pay 500,000 liras’ at this stage, then that right is effectively being denied.

The Constitutional Court laid down a clear principle. It said, ‘It’s not enough to say the door is open; citizens must be genuinely able to walk through it.’ But what we’re seeing in environmental lawsuits in Turkey is the exact opposite. The door may appear open, but you need to pay millions just to get through it. So the right to access the courts exists on paper, but not in practice.

Today, environmental lawsuits have become cases that only those who can afford top-tier lawyers and hefty expenses are able to pursue. This goes against the rule of law, the right to a healthy environment, and even the Constitutional Court’s own precedents.”

'Seeking justice shouldn’t be a luxury'

Cemil Aksu reminds us that villagers are not just defending their own land, but nature on behalf of everyone:

“These people are actually fighting on behalf of all living beings. They’re protecting forests, water, and pastures. Yet it’s the corporations that are being protected, while citizens are faced with barrier after barrier.”

Derya Tolgay echoes the warning: “If people are expected to pay these sums, no one will be able to file an environmental lawsuit. Lawsuits filed in the public interest are effectively becoming a luxury reserved for the wealthy.”

In environmental lawsuits filed across Turkey today, the key issue is not just the scientific reports, but also who will pay for them. In Gümüşhane, villagers managed to collect the 94,000 liras through solidarity. But in Marmara, the 1.5 million lira price tag stands as an enormous wall in the way of justice.

This “economic wall” facing citizens who want to defend the environment has become one of the most critical topics—not only for local struggles but also for the broader issue of access to justice in Turkey. (HA/TY/VK)