Click to read the article in Turkish

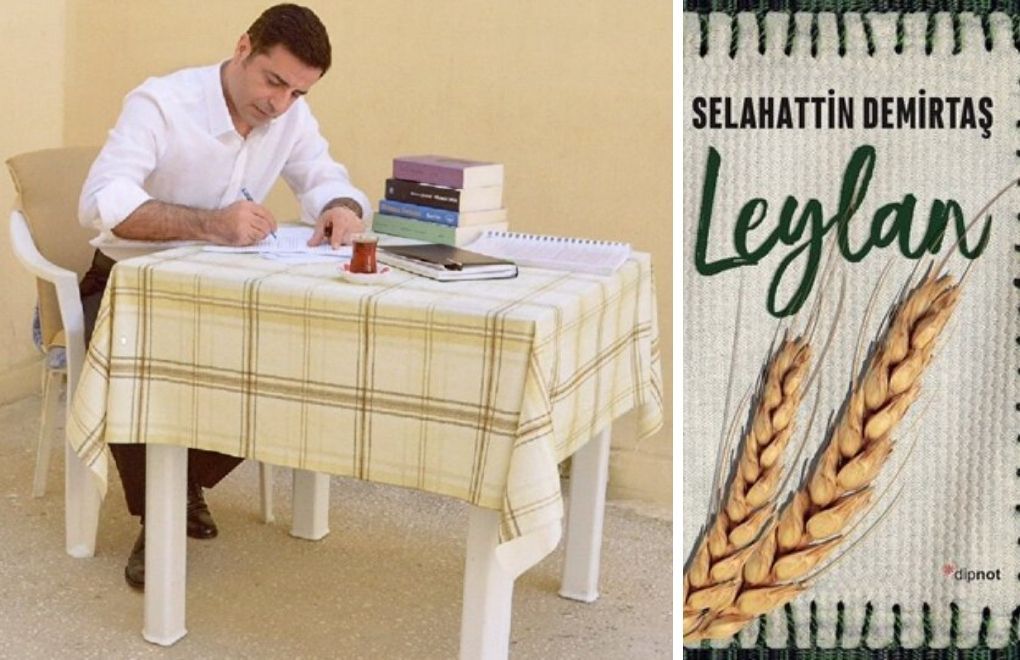

After his two short story books "Seher" and "Devran", Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) imprisoned former Co-Chair Selahattin Demirtaş has now published "Leylan", his first novel. "Every reader will get the message of the book depending on where he or she stands. As the author, it is not right for me to do any coding or draw a boundary", says Demirtaş.

Starting on the kûçes (streets) of Diyarbakır and moving on to İstanbul, Zurich and finally to Nusaybin in Mardin, "Leylan" is a multi-character, multi-layered book, a novel within a novel...

The tempo of the book never slows down, which is one of its striking features. Selahattin Demirtaş himself also says that it was especially difficult for him to fictionalize the book: "I had the greatest difficulty in putting the fiction into a perspective. I had to review and organize each and every detail, connection and character over and over again."

Dealing with the unconscious, psychoanalysis, traumas and neurology and coming closer to a crime fiction from time to time, "Leylan" is in fact a novel on the oldest search of the humankind, namely "happiness." Behind bars for over three years now, Demirtaş says, "The hopelessness and unhappiness of the people outside as well as the impression that they are gradually driven into a meaningless life made me want to write about it."

Demirtaş has answered bianet's questions on "Leylan":

After your short story book "Devran" was adapted for the stage, a debate has raged over your books, especially with remarks targeting the audience of the play. All of these happened just days before Leylan came out. Several bookstores and publishers expressed their support for the book. How did you follow this period from prison?

We tried to understand what was happening outside, partly from the press, partly from the statements of my fellow attorneys. What the government and pro-government circles did was nothing but their usual eclipse of reason and immorality. But solidarity of every stripe against it was very meaningful and it was, of course, a morale booster for us. On this occasion, I would like to once again extend my thanks to everyone.

You previously said, "Whenever the slightest idea comes to my mind, I reach for the pen." What was this first sparkle for Leylan?

"The hopelessness and unhappiness of the people outside as well as the impression that they are gradually driven into a meaningless life made me want to write something about it. Everything started by thinking about it.

'Sometimes, I paused for days for a single information'

As you also indicated in the "Thanks" part of your book, you consulted with doctors about the medical parts. However, you also say that you did not follow most of these recommendations so that you could put the fiction into a perspective. It is important for a writer to work together with an editor, a consultor and with an expert for exchange of ideas. One also has to do some technical research while writing a novel. How does this process go for a writer behind bars?

It was, of course, very difficult and challenging. I had to content myself with the verbal and written information and material communicated to me by my attorneys or the reports sent to me by mail etc. I told my attorneys what I needed, they did a research and brought it to me. I saw the documents and listened to the information in attorney's room and wrote the novel based on this information. Sometimes, I had to pause writing for days because a single information was missing and waited for my attorneys to come to visitation and bring me that tiny information. And when the information arrived, it was not easy to concentrate on writing again. Because, in the meanwhile, I had to deal with over a hundred lawsuits and numerous problems.

When your read Leylan absorbed in one story, you find yourself in another story all of a sudden. It is a multi-layered book, a novel within a novel in a sense... What did you do to put the fiction into a perspective and to keep the story dynamic?

I had the greatest difficulty in putting the fiction into a perspective. Chapter by chapter, I had to review and organize each and every detail, connection and character over and over again. I omitted some chapters as a whole and added new ones, etc. Whether it has worked out or not... I am not really sure. But, I tried to do something by making corrections based on the warnings of my friend Abdullah (Zeydan) and with the errors and gaps in fiction that he noticed. I had a fictional diagram on my mind, like an electrical one and, to be honest, it was not very easy to connect the circuits, - I mean - to write without being carried away from the main topic, flow and tone.

'The issue of mother tongue is the issue of childhood'

The book makes several references to the intertwinement of Kurdish and Turkish. "The Kurdish of love is 'evin' (your home in Turkish) and your home is your safest place on earth." On the other side, we also read that it is very interesting for a child to see that the same word means two different things in two languages. This chapter reminds me of the movie "On the Way to School." Was it an intentional choice to approach the issue of mother tongue from the perspective of a child?

The issue of mother tongue is, above all else, the issue of children, or rather, the issue of childhood. It is when both the mother tongue is learned and when people are completely assimilated. Therefore, I thought that it would be more explanatory and meaningful to deal with this issue from the point where it arises in the first place and in the most striking manner.

Kudret, the first protagonist that we meet in "Leylan", comes to have a Kurdish book by Mehmed Uzun. Not taught how to read and write in his mother tongue, Kudret says, "Even though I could understand and speak my own mother tongue, it was something else to read and write." Was this part intended as an answer to the questions on "why you do not write in Kurdish"? And will you or will you be able to write in Kurdish one day?

Yes, it is also an answer to the question why I cannot write in Kurdish or perhaps a self-criticism as well... I have to be really competent and have a perfect command of Kurdish so that I can produce a Kurdish literary piece. I practise Kurdish in prison, but - unfortunately - I have not yet got competent enough to produce a literary piece in Kurdish. Of course, I aim to write in my mother tongue one day.

In Leylan, there are real places like Ciğerci Hacı and Fazıl Usta in Diyarbakır and non-fictional characters like İhsan Fikret Biçici. Leylan is a novel interwoven on the kûçes of Diyarbakır, İstanbul, Nusaybin and Switzerland. As a person behind bars for over three years now, which place do you miss the most?

The streets of Suriçi (in Diyarbakır), where I was born and raised and which are now devastated... I am really very sorry for that, it is one of the issues that hurt me the most.

'It is not right for me to draw a boundary'

In some part of the novel, Bedirhan says, "While we are trying to add meaning to life, we forget to live the life itself." Readers are also encountered with several social issues as substories, such as Academics for Peace, male violence, burning down of villages in the 90s, even the hunger strikes in Ireland's prisons. But, can we still say that - in its very essence - Leylan is a novel on the oldest search of the humankind, namely "happiness"?

Yes, it would not be wrong to say that, but every reader will get the message depending on where he or she stands. As the author, it would not be right for me to do any coding or draw a boundary.

Perhaps, some will read it as a love story, I have - of course - no objections to that. I have already said what I had to say in the novel. The rest depends on the reader's own viewpoint, priority and perception.

Subconscious, unconscious, psychoanalysis, traumas... In the second part of Leylan, there is a story dealing with memory especially around these issues. Can it also be read as a utopia which partly gives an impression of a crime fiction wandering off to mysterious ways?

I do not think that "fantastic" parts are utopic. Technology has been already providing opportunities to do the things and obtain the results that I mention. You can see that when you look around carefully.

Does the song Min bihisti in the book have a special meaning for you?

It was a folk song that I liked listening when I was outside. I also played it for several times and am still playing it with my bağlama [an instrument with three double strings] in prison. Its melody and lyrics make me said, that is why I opted for this folk song.

How do you think the criticisms about your book will affect your future endeavours in writing a book?

Criticisms about my books help me the most in finding and correcting my mistakes and shortcomings. I have - of course - benefited from these criticisms a lot. (AÖ/SD)