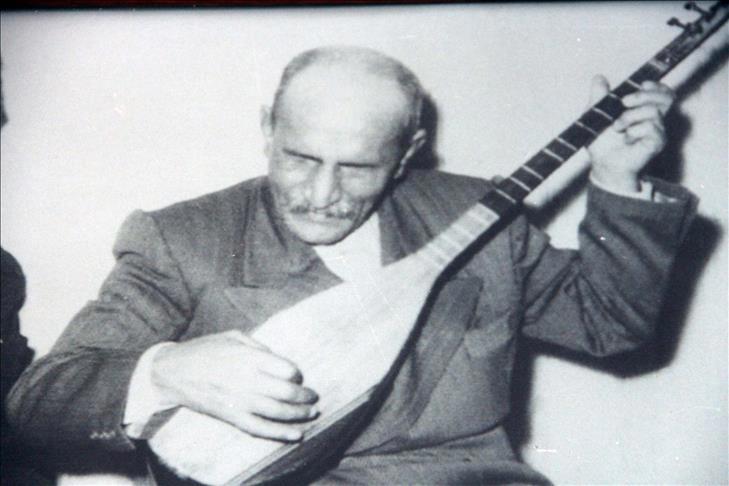

In the basement of the old Imperial Ottoman Bank, void of natural light, reels of an archival film project in black and white the story of a blind folk singer, Turkey’s own national poet, known as Âşık Veysel, whose name indicates his embodiment of the ancient bard tradition that has given history and life to the diverse peoples of Central Asia since time immemorial.

Programmed by Gülce Özkara for Salt Galata, a celluloid research project by artist Mike Bode and screenwriter Caner Yalçın investigates the censorial backdrop of the documentary film by Turkish auteur Metin Erksan, his debut feature, entitled simply, The Life of Âşık Veysel.

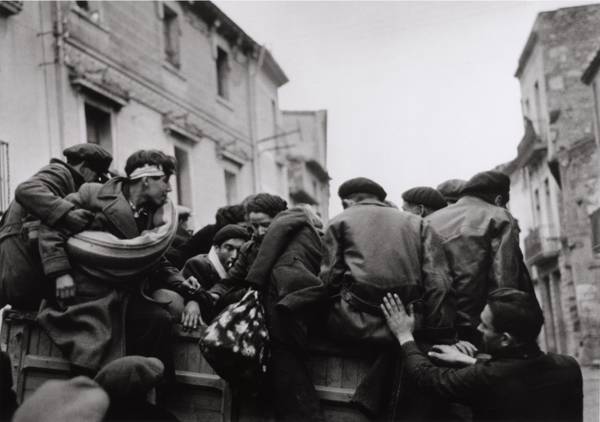

The austere cube of the exhibition hall flashes with projections of key scenes that reveal abrupt shifts in the production, the mechanical threshing of what across endless agricultural fields, Âşık Veysel in and among fellow villagers, the cave churches and geological spires of Cappadocia, and funeral processions for Kemal Mustafa Atatürk at Dolmabahçe Palace in İstanbul, where, in 1938, Turkey lost its nation’s founder.

It is the representation of the land, its agrarian fertility in particular, and the economic station of the local people of the central Anatolian region of Sivas, Âşık Veysel’s birthplace, that came under scrutiny by governmental authorities responsible for media oversight in the early years of the Turkish republic.

Censorship and American fields

Despite the completion of the film in 1951, censors blocked its release on three occasions for the next two years. When it finally saw the light of day in 1953, it had been utterly transformed by influences of external intervention that, in retrospect, appeared to have had ulterior motives considering the propagandistic splicing of footage that, as corroborated by Bode and Yalçın, could be sourced from United States Information Service stock film of combine harvesting in Hudson fields in the state of Delaware.

As screened piecemeal to exaggerate curatorial and artistic insights at Salt Galata (the full, extant film is also viewable online), the split of added scenery is stark in terms of aesthetics and content. Suddenly, in a jump cut, from dirt plowed against a rugged highland, men sit almost languorous atop massive machines against a perfectly flat horizon expanding outward with interminable farmland, ostensibly tall grasses of wheat or a similar cash crop ripe for stimulating the national economy.

The augmentation of sheer scale and automated efficiency is contextualized in Erksan’s film by the passage of time in the life story of Âşık Veysel. He strums his long-necked lute against titles superimposed with the years of the 1930s until 1938 fades to Atatürk’s memorial. In a diptych, Bode and Yalçın presented the farming and commiserating together in a gesture that animates the history of Turkish nation-building.

Blindness and vision

Dark World refers to the original subtitle of Erksan’s film, which was removed by censors as it connotes a stripe of 20th century social realism that, while viscerally expressed in much of the surviving film, could not be so explicit. It is, apparently, also a convenient metaphor for ongoing mandates of media censorship that continue to weigh the Turkish film industry, as well as the arts in general and the cause of free expression broadly across the greater region.

Conceived by one of Turkey’s proudest filmmakers, Erksan also made the timeless classics Time to Love and Dry Summer, and written by the canonical artist Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, whose reputation for screenplays was practically zilch, The Life of Âşık Veysel is a lucid, however strained, evocation of realist cinema in Turkey, and presents an archetypal biopic of the tragic hero.

Blinded by sickness as a child, later losing two infant daughters to the pandemic of infant mortality that plagued Turkey’s heartlands prior to the arrival of modern institutions of medicine, education and agriculture, what the Anatolian people starved for in terms of physical substance they made up for by the richness of their cultural heritage, shared among peoples whose lands continue to expose untold mysteries of the human story. That was the treasure that remains of Âşık Veysel, beloved not only by his local kith and kin but by people from across Turkey, whether contemporary artists of İstanbul or the tea-drinking gamblers of Sivas.

One of the immediate images exhibited at Dark World, by the entrance into the hall, is a pair of photographs shot in Veysel’s hometown of Sivrialan (Sivas) in 2019, it shows modest homes and sparse vegetation within the hilly territory. Across from it is a print by Eyüboğlu, of Veysel, playing his lute amid plant life, a single eye beaming in his shadow. His example bridges high and low culture, elites and commoners. However inadvertently, his legacy is not only his art, but blindness, that of his own, and of his people. (MH/VK)