Photo: Mustafa Avcı

Click to read the article in Turkish / Kurdish

This article is published as part of the "In Good Times and Bad: Living Together" project of the Hafıza Merkezi Berlin (HMB) and IPS Communication Foundation / bianet. |

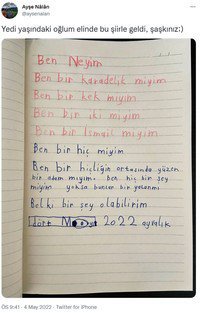

On May 4, 2022, a mother shared a poem titled "What Am I?" written by his son İsmail on Twitter. The poem where İsmail tells his existential pains in a pretty sweet, kind of mischievous way went viral in a short period of time. The poem, which was shared by thousands of accounts and appeared in newspapers, literally vibrated people's heartstrings.

Shortly after the poem was shared, a musician named Ufuk Beydemir shared a video where he composed music for the poem.

I came across İsmail's lyrics on Twitter and could not stop myself. İsmail turns out to be a seven-year-old wise friend.

My seven-year-old son came up with this poem, we are astonished :)

This pleasant composition venerating the poem, without any disrespect, taking a kid's existentialist mischief and pains seriously, and indeed making it more sorrowful by taking them too seriously, was shared by tens of thousands of accounts too. Over one day it was viewed 675 thousand times just on Twitter.

What is creativity?

There are several different answers provided by different disciplines to the question of what creativity is, but if we consider the issue with reference to this example, it can be seen that creativity has the power to set other people's feelings in motion, to trigger their creativity, and to do this at a social level. Of course, all creative products cannot be expected to have such a strong social response, yet how great the creativity's capacity to mobilize the society and people is can be understood based on creative productions that have already had such a social response.

Vibration of music

The capacity of music to set other people in motion can in fact be thought of as an inherent property of sound, the basic building block of music. This property of sound can be observed in the very phenomenon of resonance. Of course, the mobilization of people listening to music cannot be explained by the notion of resonance which is a physical phenomenon. Still, the notion of acoustic resonance can metaphorically help understand the contagiousness of music and creativity. Acoustic resonance is an acoustic system's amplification of the soundwaves in its natural frequencies of vibration. This phenomenon can be observed in everyday life too. For example, when the lowest string of one of the two guitars both tuned in a standard way, in the same environment, is struck strongly enough, the other guitar's low string also starts to vibrate "by itself." Strings with the same resonance frequency set each other in motion via airborne soundwaves, even with a physical distance between them. When the string of the first guitar is stopped, it is observed that the other's low string continues to vibrate and to make sounds on its own.

*A video exemplifying acoustic resonance by using two identical tuning forks (diapasons)

Vibration of hearts

Similarly, artistic creativity can vibrate people's heartstrings and set them in motion both emotionally and physically. Just the way writing a poem vibrates the heartstrings of the young poet İsmail, sharing this poem afterwards vibrates his mother's heartstrings, ultimately reading it vibrates millions of people's heartstrings. This effect appeared in a stronger way in the musician Ufuk Beydemir, and paved the way for him to contribute to this poem with a new composition by triggering Beydemir's creativity. Hence, Beydemir's statement that he could not stop himself and composed music for it can be in fact compared to a strong emotional resonance.

Music: Universal human addiction

Musical work as an intangible, invisible artwork, is perhaps the most lasting, the most effectful, and the most wandering in terms of its influence on people among all arts. In addition to these, music is like an "addiction" whose reason scientists have difficulty to explain. This universal human addiction can bring together even seemingly unrelated people by overcoming distances. Even though people listening to musical pieces can emotionally feel different things, music joins them in different and plural affectivities that cannot be identified ahead with certainty, thanks to a "floating" intentionality innate to music.

Music, people, and entrainment

After mentioning this affective togetherness produced by music, it is indispensable to talk about the capacity of people to synchronize physically and intellectually with a rhythm, namely about entrainment. Thanks to their entrainment capacity, people can temporally entrain to a rhythm and to music, they can move and dance in unity, together, as one body. Quite similarly to acoustic resonance, music's rhythm hanging in the air triggers an intellectual mechanism, makes people entrain to music and hence to each other. Thus, while allowing people to feel different emotions, music also enables people to be in an almost perfect physical/intellectual harmony. At the root of the powerful and transcendent emotions that bring people together, join them in music perhaps lies this connectivity of music allowing for differences.

Cultural meanings of the notion of creativity

Creativity, on the one hand, is a property attributed to gods in different cultures; on the other hand, it is a phenomenon observed in everyday behavior of people (when speaking or solving the problems they face) and even in animals. In Ancient Greece and Rome (even until Renaissance Europe), the notion is attributed to entities other than humans to a great extent. According to this view, humans are tools to convey the inspirations of creative forces like fairies, daimons, geniuses, semi-gods, and gods. Creativity began to be viewed as a property of humans and individuals with the Renaissance. This view glorifying the creative individual reached its peak with the Romanticism movement.

The notion of creativity is a somewhat more complicated issue in Islamic geography. The main reason for this is the strong circulation of the orthodox idea that views creativity as a property reserved for Allah and does not consider it as a human property in any way. Those looking at creativity from this perspective tried to preclude novelty and creativity through ways like bidʿah and ijtihad. Despite these obstacles, artistic production still continued through some "creative" solutions. For example, some zakir approaching the matter with a similar sensitivity, did not use the concept of composition because of its creativity nuance, instead preferred to use terms like rumbling or dressing.

Podcast series of In Good Times and Bad are available on Spotify, ApplePodcast, Youtube [Turkish]

In Turkey, in addition to those objecting to the idea of creation from a religious perspective, there is also a viewpoint not considering the idea of creation as a merit of everyone from a secular perspective. This is a self-orientalist viewpoint that considers classical Western music to be a more superior musical genre, is under the influence of the image of semi-godly, oracle, genius composer of polyphonic musical pieces introduced by Romanticism, despises the composers of monophonic pieces, and only views the composition of polyphonic pieces as authentic.

In Turkey, another conflict about creativity arises in the discussion of whether a folk song is composed. This discussion appeared especially in the framework of TRT's folk-music broadcast and went on quite intensely until the 2000s. This mentality that appeared within TRT and has an essentially populist ideology, in some cases, acted with a point of view despising the living people while glorifying an idolized people of the past. We can observe these discussions about creativity in the context of Turkey also in the history of music studies.

Creativity in folklore studies, musicology, ethnomusicology

By looking at the myths about the origin of music and musical instruments in different societies, it can be seen that music is closely related to the divine, supernatural, magical, and sacred. Historically, music and myth are almost interwoven. In his book investigating the myths of South America's natives, the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss distinguishes music, which he defines as a language understandable and untranslatable at the same time, from other types of art. He states that the creator of music, the greatest mystery of human science, is a being comparable to gods.

With the 1950s, especially thanks to the studies within psychology, the long-standing view of creativity as sacred, mystical, under the monopoly of a few people started to be destroyed. These studies allowed understanding that creativity is a phenomenon observed in humans on a daily level. At this point, the linguist Noam Chomsky's studies showed that even speaking a language is a talent that requires a great deal of creativity on its own. The problem-solving skills acquired by not only human beings, but also animals showed that animals too are creative to an extent, within some limitations.

According to the ethnomusicologist Laudan Nooshin, the mythologic and sacred character attributed to creativity caused the ideologies and power relations behind creativity to be neglected. Hence, it is crucial to look at these relationships that determine the rules about how to define creativity, who creates, what kind of a value will be attached to the creation. In this sense, in order to understand the social customs that bring out creativity, it is mandatory to scrutinize the social, class, ethnic, religious, economic and gender conditions.

People's capability to create

One of the important topics in folklore studies, also resonating with the discussions about folk music in Turkey, is the question whether the public has the capability to create or not. At this point, it has even been suggested that people pursuing a life closer to nature also produce closer to natural (even animalistic in some sense) too. There are even theories that do not attribute any creative subjectivity to the people while attributing a subjectivity to the folk song itself. For example, Joseph Grimm's claim that "folk songs compose themselves and transfer themselves to the next generations" is pretty interesting in this sense. Although ideas about the public having creativity appeared and began to be accepted earlier in the 20th century, even today there are folklorists defending the idea that the public is not creative.

As stated before, the emergence of the composer as a genius and even a semi-godly creator in Europe started with the Romanticism movement in the 19th century. As a result of this, a cult of worshiping the composer, ignoring the musician and the audience emerged. This viewpoint glorifying the composer as a creator continues to a great extent today both culturally and in the field of musicology. According to the musicologist Christopher Small, musicology concentrates not on the general act of creating, the audience's perception of the work or the audience's reactions to it, but on the created musical object (the musical note) itself. This perspective based on Romanticism disregards the collective and social structure of human production. However, there are texts emphasizing the cultural continuity of creation and collectivism even in the mid 20th century. For instance, in his work about innovation published in 1953, the anthropologist H.G. Barnett states that people do not produce cultural goods out of nothing, they produce by bringing together the already existing building blocks.

In the first stages of ethnomusicology, which appeared in the early 1950s, there were also studies showing that illiterate people could be creative, even though the interest was mostly on the social rather than the individual. In the 1970s and 80s, creative individuals' names were mentioned more in ethnomusicology and the issue of creativity has started to appear more among the study matters of ethnomusicologists in recent years.

"Musicking"

The sociologist Jason Toynbee states that studies conducted within disciplines approaching music from a cultural perspective and especially within cultural studies care very little about creativity. Toynbee, who thinks that the factor causing this situation is the set of populist tendencies dominating the discipline, claims creativity is associated with high arts, and the line of argument that high arts are elitist, so cannot be a research subject for cultural studies interested in public's culture might have been influential in this situation. Cultural studies remained interested mainly in the consumption of cultural goods and focused on the creativity shown by people when listening to music and when dancing.

Musicking is one of the concepts that needs to be mentioned in these discussions. The musicologist Small, suggests using the verb musicking which defines music as an act taking place at the time of performance instead of an object or a thing. The verb of musicking that extends creativity to all the participants means the involvement of people in the musical performance in an active manner as performer, as listener, by dancing, by practicing, by rehearsing, by exercising, by singing, by murmuring, by whistling, by composing. Small, with the verb of musicking, extends the source of creative energy in the music to all participants of any given professional, amateur or everyday musical activity, criticizes Western musicology for being trapped about creativity.

Obstacles to creativity

In his book titled Free Culture, Lawrence Lessig talks about the big changes in the production of cultural goods with the advances in Internet technologies. Lessig, who emphasizes the big media companies' reproduction of the Internet for their own interest, states that companies control culture and creativity in this way. According to him, big companies manipulate law to protect their interests under the excuse of preventing piracy, gradually eliminating the difference between commercial and non-commercial culture. This, in turn, caused the cultural distinction between free culture (publicly owned) and controlled culture (whose rights are controlled by law) to almost vanish. Because of all these, the creativity of ordinary people and therefore culture has started to go under legal regulation like never before; at the same time, culture has turned into someone's property like never before in history.

Historically, it can be seen that the value attributed to creative individuals oscillates between two extremes. While the first of these ignores people's creativity and attributes creativity only to transcendental beings other than humans, the second ignores the social character of creativity, glorifies, even divinises the individual, and views creativity under the monopoly of geniuses. As creativity studies show, it is not something under the monopoly of only individuals with a special talent, it is a capability present in all people and is a result of humanity's collective culture. Harsh copyright laws which protect the interests of companies and famous musicians in the first place prevent musical pieces from being reproduced by other musicians in a creative manner. While music creators of the previous generation could freely reproduce their predecessors' music in a creative way, today's musicians are deprived of this right. Thus, in order for creativity and novelty to continue, copyright laws should be reviewed in a way that will not block out new creators.

In Good Times and Bad: Living Together Article Series

1- Family: In good times and bad...

2- Is it possible to live together in the presence of impunity?

3- Politics of horror and the cinema

4- What can hatred be washed off with?

About the projectThe podcast and article series "In Good Times and Bad: Living Together" are prepared as part of a project run by the Hafıza Merkezi Berlin (HMB) and IPS Communication Foundation / bianet. The coordinators of the project are Özlem Kaya from the HMB and Öznur Subaşı from the IPS Communication Foundation. The project advisor is Özgür Sevgi Göral and the project editor is Müge Karahan. With a focus on "living together", the series will address the themes of family, punishment, fear, hate, creativity, racism, memory, lie, anthropocene and friendship. The episodes will be published every 15 days on Tuesday. |

[1] There are also those who think that the mother wrote the poem, or the mother wrote it together with the son. There is no way to know this, I believe that İsmail wrote it. But if his mother wrote it and shared it in his son's handwriting, this can be thought of as even more creative.

[2] See the studies of psychologist Ian Cross for the concept of floating intentionality.

[3] Research in neurosciences suggests that the neurons in our brain synchronously fire to musical rhythm. Similarly, the brain waves of the people that make music together can be synchronized with the same rhythm. For further details, “Neuroscience Reveals How Rhythm Helps Us Walk, Talk — and Even Love” ve “Duetting Guitarists’ Brains Fire to the Same Beat”.

[4] Term used for innovations that appeared after the prophet Mohammed, "beliefs, worship, ideas, and practices not founded by religious evidence." The word is derived from a root that means "to invent, to create without any precedent, to build," so it has a reference to creating. Translated from https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/bidat. T.N. See https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/bidat.

[5] See Mustafa Avcı, “Bestenin Anlam Dünyası: Yaratma, Hatırlama, Bulma ve Keşfetme Ekseninde Müzik Üretimi”, Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 18, sy 48 (2021): 54-78.

[6] See https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1844386#page=5 for a memoir of Aşık Kul Ahmet about his folk song Yoh Yoh in TRT. T.N. Mustafa Avcı, "Bestenin Anlam Dünyası: Yaratma, Hatırlama, Bulma ve Keşfetme Ekseninde Müzik Üretimi", Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 18, 48 (2021): 54-78. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1844386#page=5

[7] Laudan Nooshin, Iranian Classical Music (Ashgate, 2015), 3-4.

[8] Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked (Harper & Row, 1969), 18,

[9] Mark A. Runco ve Steven R. Pritzker, Encyclopedia of Creativity, 2. ed, c. 1 & 2 (Elsevier, 2011).

[10] David C. Fossum, “A Cult of Anonymity in the Age of Copyright: Authorship, Ownership, and Cultural Policy in Turkey’s Folk Music Industry” (Doktora Tezi, Brown University, 2017), 44.

[11] Christopher Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening (Wesleyan University Press, 1998), 4.

[12] Bruno Nettl, The Study of Ethnomusicology (University of Illinois Press, 2005), 261.

[13] Jason Toynbee, “Music, Culture, and Creativity”, The Cultural Study of Music, ed. Martin Clayton, Trevor Herbert, ve Richard Middleton içinde. (New York and London: Routledge, 2011), 161.

[14] Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock down Culture and Control Creativity (Penguin Press, 2004).

(MA/SO/NÖ/VK)

.jpg)