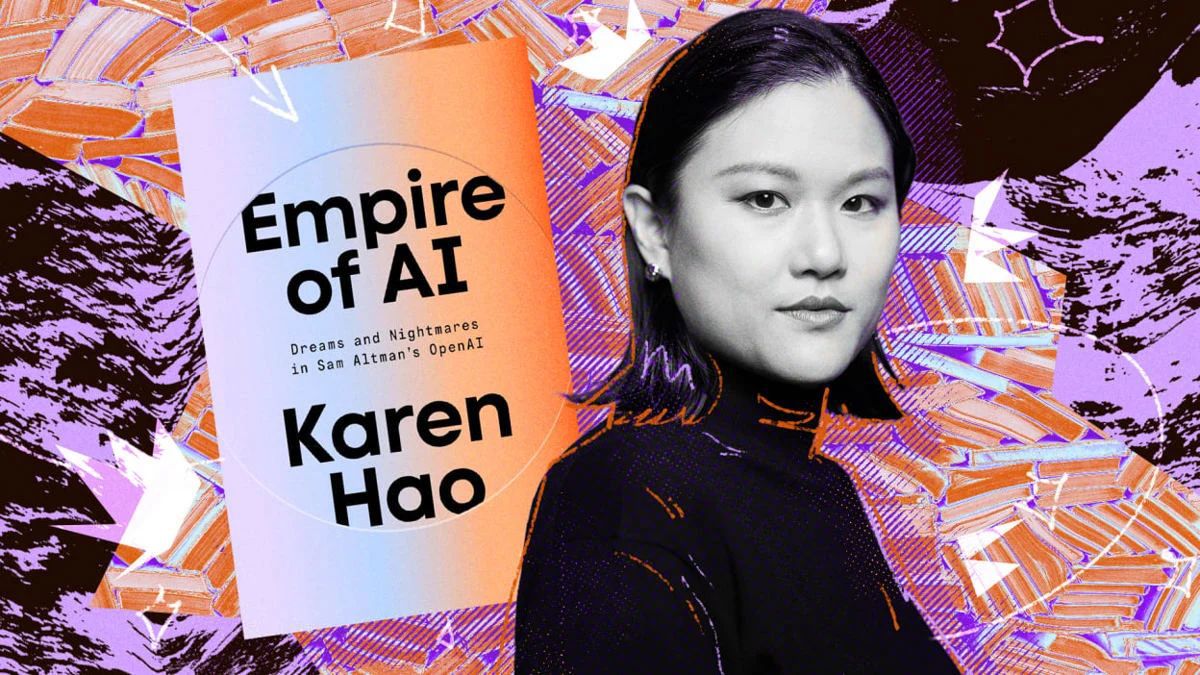

In this episode of our series, The Political Construction of AI, we share an in-depth conversation with investigative journalist Karen Hao, centered on her book, Empire of AI.

In the interview, Hao reveals how tech giants act like modern empires, consolidating their power by exploiting data, labor, and natural resources, and by monopolizing the production of knowledge. She exposes how narratives like the “utopia-apocalypse” dichotomy and the abstract “cloud” metaphor are used to mask the industry’s massive ecological toll, global labor exploitation, and the censorship mechanisms that suppress academic freedom.

So, is an alternative to this colonial tech architecture possible? Hao offers a hopeful way forward from this grim picture. By examining the community-focused and consent-based AI model of the Māori people in New Zealand, she outlines a concrete vision for how technology can be rebuilt for the benefit of humanity and the planet. According to her, these fundamental principles, which may seem “radical” today, are in fact the building blocks for a more equitable technological future.

'Companies grab a lot of land'

Your book’s title is quite ambitious: “Empire of AI”. What are you aiming to convey with this empire metaphor? What resources do today’s tech giants exploit and which domains do they annex to sustain this empire?

The first thing I wanted to convey was that these companies are not just businesses; they are political and economic agents consolidating extraordinary amounts of power along multiple axes. Secondly, their behavior directly parallels that of historical empires. They literally grab a lot of land to build the data centers they need to train their AI models.

They usurp a lot of people's data for training those models. They exploit a lot of labor—both the labor that goes into developing the models, as well as the impact their models are now having on the workforce. And they monopolize knowledge production by having hired up most of the top AI researchers in the world today.

So, most AI research produced is filtered through the lens of what the companies want, and the science itself is fundamentally distorted in favor of their agenda. Lastly, they engage in the narrative that there are good versus evil empires, and they have to be a “good empire” to be strong enough to beat back the “evil empire”—just in the way that the British Empire used to say they were better than the French Empire.

The French Empire said they were better than the Dutch Empire, and every empire portrayed itself as the morally superior one. In this morally superior frame, the empire says that what it's ultimately doing is to bring progress and modernity to all of humanity. And that is exactly what OpenAI says. It says its mission is to benefit all of humanity, even with all the resource plundering that it's engaged in.

When discussing artificial intelligence, we always hear two extreme scenarios: either a utopia or an apocalypse. You argue that both of these narratives serve the interests of those in power. How does this utopia-apocalypse dichotomy thwart regulation efforts by distracting our attention from concrete, present-day problems like labor exploitation and ecological consequences?

Exactly. They’re two sides of the same coin because they both portray AI as all-powerful, as inevitable, as an unstoppable force and, as you mentioned, they distract from the actual problems. Neither the utopia people nor the dystopia people very often acknowledge that there are extremely at-scale, present-day harms happening right now. When I first started the book, I was surprised because I thought most of this was rhetoric—that people in the utopia/dystopia camp were just saying these things to help with their marketing.

But I learned that it's not actually rhetoric. Some of the people who say these things have deep-seated beliefs that this is real. There are people who genuinely believe that AI might kill everyone and have dedicated their lives to preventing that possibility, based on the visceral fear they have of this outcome.

So it’s more complex than purely saying it is a rhetorical device, but it has also become a convenient one for politically savvy executives using these narratives—which have bubbled up from genuine concerns or excitement—as a way to navigate and ward off regulation.

'There are multiple levels of censorship layered into the industry'

In your book, you place special emphasis on the firing of Timnit Gebru by Google. This case once again demonstrates that it is impossible to speak of scientific freedom and corporate transparency in the AI industry. What methods do companies use to silence critical research that conflicts with their profit motives?

There are a lot of mechanisms. The research that is produced now has to be thoroughly reviewed by both the legal and communications departments. And whether or not a researcher is even given the opportunity to pursue a particular research question is also in the air.

So, if a researcher gets to the point where they have the resources to conduct certain types of research, there's already a significant filter on who gets to that point. But in addition, and not just regarding research, if any employee—researcher or not—sees something problematic or wants to convey concerns to the public, there can be severe consequences for doing so. The mechanisms companies use have become even more forceful than what Google did to Dr. Gebru.

They will be even more aggressive about firing people as examples of the consequences that will befall someone who tries to leak or communicate to the press. And so there are multiple levels of censorship layered into the industry, which they use to control the type of information that ultimately reaches the public.

And we know that in OpenAI case, OpenAI transformed from a non-profit lab into a Microsoft-backed tech giant. What does this transformation tell us about the future of other tech startups in Silicon Valley?

Basically, it shows us the incentive structures within Silicon Valley that make it highly improbable for any organization to continue being mission-driven over profits. In OpenAI's case, it's not just the system-level incentive structures, but also the people who work at OpenAI. They are all products of Silicon Valley.

Sam Altman, the executive, was a product of Silicon Valley. All the other executives came out of the Silicon Valley model of innovation. So they grew up in their careers embedded within the ethos of the “move fast, break things” ideology, the blitzscaling ideology, and the aggressive chase for hockey-stick user growth.

And all of the people they hire are also from these other tech companies. So it is very difficult to break out of that entrenched model of what is considered innovation and how a startup should operate when it is swimming in an environment that has defined very strong cultures and norms around those things.

'Silicon Valley has had an illiberalizing force'

The “China threat” narrative is frequently used in AI policymaking, particularly in the US. This can be seen in the recently published “AI Action Plan.” How do tech companies leverage this geopolitical competition as a trump card to receive state subsidies on one hand, while evading regulations on the other?

They basically say that “if you do not allow us to have unfettered access to resources, then China will win, the world will end or become communist, the US will lose, and human rights will disappear”. What I always say to that argument is to look at the track record of what that argument has gotten us.

Silicon Valley has argued that without regulation, they will beat China and have a liberalizing force on the world by outcompeting Chinese platforms. Instead, the exact opposite has happened.

The gap between China and the US has continued to close, and Silicon Valley has had an illiberalizing force around the world. So it’s pretty clear from the evidence and the track record that these narratives are simply intended to serve the tech industry in the US.

Behind the “autonomous” facade of AI lies a vast, invisible army of human labor. You describe in your book how Kenyan data labelers are exposed to traumatic content in order to “cleanse” the systems. How does this global division of labor, which you term “disaster capitalism,” sustain the illusion that technology is intelligent and independent?

The AI industry engages in the same kind of labor outsourcing that many other industries do, finding places that are far away and off the radar of their average consumer to perform the dirtiest work. In the AI industry, however, there's an additional layer.

Anyone who buys clothes has an inherent understanding that they were made by someone, somewhere. With AI, that fundamental assumption isn't there because most people don’t understand that digital technologies have a very physical footprint and that a lot of labor is involved. By doing the same kind of outsourcing that other industries have done, it enhances the “magic veneer” created for their AI products.

'Data centers exacerbate climate crisis'

There is also a widespread perception of AI as an abstract “cloud” technology. However, you document how Microsoft’s data centers are depleting water resources in arid regions like Chile and Arizona. How does this “cloud” metaphor obscure the heavy ecological toll of artificial intelligence on our planet?

There are multiple layers of consequences, and it’s not just to the planet; it’s also to public health. The amount of computational infrastructure being built right now—the number of data centers and supercomputers—is unprecedented.

Regarding the energy needed to support these data centers, projections say that in the next five years, we would need to add 0.5 to 1.2 times the energy consumed by the United Kingdom, or two to six times the energy consumed by California, onto the global grid. This is already starting to strain the electric grid and undermine the energy security of communities. Furthermore, most of that energy will be sustained through fossil fuels.

This leads to a huge increase in carbon emissions and a great increase in air pollution within the communities that host the burning of those fossil fuels. There is also the water footprint, as data centers need fresh water to cool their equipment.

Most of these data centers get that fresh water from public drinking water supplies. A recent Bloomberg investigation found that two-thirds of data centers being built for the AI industry are in water-scarce areas that already lack sufficient drinking water.

It exacerbates the climate crisis, the energy crisis, the clean air crisis, and the clean water crisis, and it hikes up people’s utility bills along the way.

You conclude your book on a hopeful note, citing the example of the Māori people of New Zealand, who are using AI in a non-colonial, community-centered way to preserve their own language and culture. What lessons can we draw from the Māori example?

I really love the Māori example. The lesson I would draw is that in developing their own AI models, they turned all the assumptions of typical Silicon Valley AI model development on their head.

First, even before they started developing the model, they asked their community whether they wanted it—which is something you never see. No Silicon Valley company asks the world whether they want an AI model; they just develop it and unleash it onto the world.

That was a profound break from the status quo. Second, they got fully informed consent for all the data used to train the model and engaged the community in a participatory development process, teaching them what AI is and why the data was needed.

They engaged the community in recording high-quality data samples and then asked what types of language learning tools they wanted them to build. They also created a commitment with the community to protect and guard their data, ensuring it wasn’t shared indiscriminately but intentionally with people who would benefit the Māori community.

They have a legally binding license where people who access their dataset must agree to certain principles for what they can and can’t do with the data. All of those are best development practices; every AI model should be developed like that.

Unfortunately, it’s sad to think that such basic principles are considered radical. Hopefully, one day they can become the norm. (DS/VC/VK)