President Erdoğan, accompanied by his spouse Emine Erdoğan, addresses his supporters near his residence in Üsküdar, İstanbul, following the victory in the presidential runoff vote on May 28. (Photo: AA)

As a result of a successful collaboration with other parties in the 2019 local elections, Turkey's main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) managed to wrest control of İstanbul and Ankara, ending the 25-year dominance of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's ruling party and its predecessors in these cities.

The underlying factor in these victories was the CHP's ability to secure the backing of both the right-wing nationalist Good (İYİ) Party and the Kurdish-focused Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP).

This success in the local elections bolstered hopes ahead of the dual polls in May that the end of Erdoğan's era was approaching. Yet, the president both defeated CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, backed by an even wider coalition including two splinter movements from his AKP, and maintained the parliamentary majority with his allies.

The defeat in what was considered Erdoğan's toughest elections amid dire economic challenges has caused fractures among the opposition parties, as well as an internal struggle within the CHP. This may lead to the lack of a wide coalition against the ruling bloc in the upcoming local elections scheduled for the end of March next year.

After months of criticism towards the CHP and mixed signals about the local elections, the Good Party declared on Wednesday that it would run independently, following a meeting of the party's executive board.

The Green Left Party, the successor to the HDP, had already indicated its intention to field its own candidates, albeit without entirely ruling out the possibility of cooperation.

Future possibilities

Given that there are still more than six months until the elections and that these politicians have a track record of backtracking from their bold statements, it's too early to completely rule out a broader coalition against the ruling bloc.

However, the challenges are greater than before. Firstly, the very idea of forming the broadest coalition possible to defeat Erdoğan suffered a serious blow in the last election. Before the runoff vote, Kılıçdaroğlu even secured the support of the ultranationalist Victory (Zafer) Party, in addition to the so-called Table of Six and the pro-Kurdish Green Left, yet still couldn't defeat Erdoğan.

This conclusion is underscored by the stances taken by both the Good Party and the Green Left, as they now assert their roles as proponents of a "third way," separately, of course, in Turkey's evolving political landscape.

In a speech in late August, Good Party leader Meral Akşener said the bipolar political landscape created by the current alliance system "deepens polarization and benefits the ruling power."

In an interview with well-known journalist Fatih Ataylı on his YouTube channel last week, she repeated these views and said "we are determined not to take part in this alliance system."

When asked whether they are willing to risk the AKP winning the local elections due to this decision, she replied, "We are willing to risk everything. Perhaps our candidates will be elected."

It's also worth noting that Akşener has ruled out any "direct or indirect cooperation with separatist movements," apparently referring to the Green Left.

Nevertheless, the mayors of Ankara and İstanbul, both confirmed by Kılıçdaroğlu to seek re-election, remain optimistic that Akşener could return to the alliance.

Ankara Mayor Mansur Yavaş, who shares the same nationalist background as the Good Party, said, "A lot can happen until the election. We will see if the decision changes," as quoted by Saygı Öztürk, the representative of the Sözcü media group in Ankara.

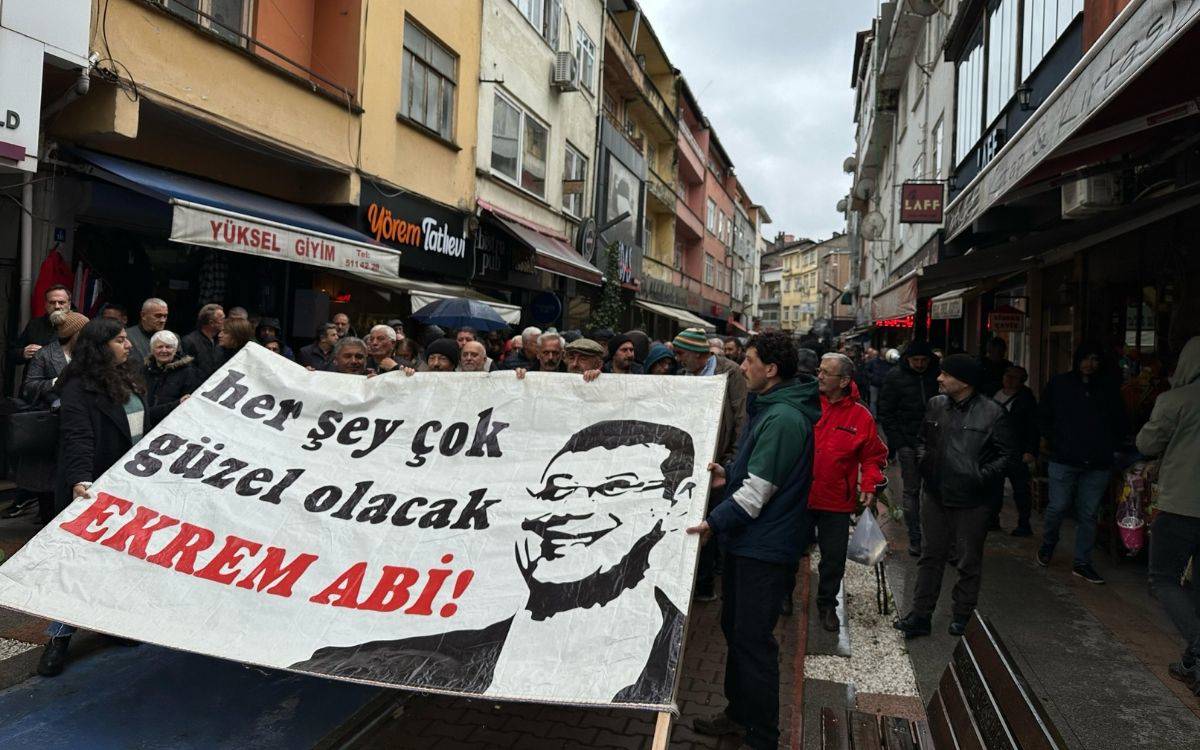

İstanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu also expressed his belief that an alliance was still necessary, and that Akşener had not closed the door on it.

Meanwhile, it's noteworthy that Akşener had touted for the presidential candidacy of İmamoğlu or Yavaş rather than Kılıçdaroğlu, due to their popular support. This dispute caused a brief rupture in the opposition alliance just about two months into the May elections. After the elections, Akşener criticized the mayors for not showing courage to become a candidate.

Both mayors are unlikely to defeat AKP candidates without the support of the Good Party and the Green Left. In 2019, İmamoğlu won the mayoral race by a margin of only around 13,000 votes. After a rerun election due to allegations of irregularities, the margin widened to 10 points. In Ankara, Yavaş defeated the AKP candidate by only 3 points.

In the parliamentary election in May, the Good Party received 8% and 12.8% of the vote in İstanbul and Ankara, respectively, whereas the Green Left got 8.19% of the vote in İstanbul and 3.19% in Ankara.

The situation is similar in Adana, Mersin and Antalya, three greater cities where the CHP took over from the AKP in the last election.

A possible change in the CHP leadership could add another variable to whether the CHP can bring together the Green Left and the Good Party.

Özgür Özel, the leader of CHP's parliamentary group, announced his candidacy for the party leadership today. He immediately got the backing of İmamoğlu, who has spearheaded the anti-Kılıçdaroğlu movement in the party since the May elections. The date of the party congress will be decided after October.

The Good Party

One reason behind Good Party's decision could be their failure to achieve the expected vote share in the last two elections where they collaborated with CHP.

The party was founded in 2017 by a group of politicians who split from the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the main allies of Erdoğan. The party received slightly less than 10% of the vote in both the 2018 and 2023 elections.

Following the May elections, some senior party figures contended that the alliance with the CHP had incurred them a loss of votes. According to their assessment, the party's attempt to establish itself as a center-right entity fell short in capturing the support of right-wing voters who remained skeptical about the CHP.

Right now, the party may be prioritizing expanding its voter base over incurring an election loss to the AKP by backing the CHP, as implied by Akşener's words in the Youtube interview, "We did not establish this party to make the CHP win elections."

The Green Left

The Green Left has also indicated its inclination to run independently in the local elections, although not as emphatically as the Good Party.

The co-spokesperson and Member of Parliament for the Green Left Party, İbrahim Akın, told Artı TV, "We believe that it is not possible to provide unconditional support like we did in the 2019 elections under current circumstances."

Implicitly referring to the Good Party's stance, he added, "It is difficult to come together with approaches that ignore [us]. If this situation changes, we are open to dialogue. If not, we are ready to chart our own course."

Nevertheless, the party's main priority appears to be its own recovery following the disappointing election results rather than focusing on cooperation with other parties.

After the two-day congress on September 10-11, the party released a declaration, directing substantial criticism towards the main opposition over its silence against the persecution of the Kurdish political movement. In particular, it mentioned the CHP's inaction towards the government's takeover of almost all the municipalities won by the HDP in the 2019 election, and the lift of the legislative immunities of HDP deputies.

The pro-Kurdish parties may have supported the CHP as the "least-worst" option in the past two elections, but they might now struggle in finding a compelling reason to continue doing so. With Erdoğan securing the presidency regardless, and the CHP's moderated nationalism falling short of their expectations, it may not make much of a difference whether the AKP or the CHP wins the mayoral races in İstanbul and Ankara.

The Green Left's declaration also highlights this, reiterating their commitment to build a "third way against the two hegemonic class blocs."

For the 2024 elections, the declaration sets the party's target as to take back the municipalities in Kurdish majority provinces that are run by government-appointed officials. The mayors had been dismissed by the Interior Ministry due to "terrorism-related" investigations against them.

With opposition parties in this state of disarray, Erdoğan continues to emphasize his determination to win back metropolitan municipalities, notably İstanbul and Ankara, from the CHP.

Regaining control of municipalities holds significant importance for Erdoğan on several fronts. İstanbul, in particular, carries symbolic weight, being the place where Erdoğan was elected the mayor in 1994, marking a pivotal moment in his political journey.

Furthermore, including the municipalities taken from the AKP in 2019, the CHP runs 11 major metropolitan municipalities, which translates to billions of dollars in public resources falling under opposition control. Moreover, holding sway over local governance in the country's largest urban centers empowers the opposition to back their words with deeds, providing them with a platform to make propaganda by showcasing their achievements.

As the current situation stands, Erdoğan's efforts to reclaim these municipalities from the opposition appear to have a smoother path ahead. (VK)