Dr. Çiğdem Çıdam was a guest on the vodcast of Turkey Beyond Borders 2.0, with her seminar titled "Remembering Gezi After Ten Years: The Possibility of Resistance, Memory, and Future Struggles," which was published on September 30, 2023.

We discussed the Gezi Park protests of 2013, the subsequent developments, and the Gezi Trial with Çıdam, who provided insights into the reflections of the resistance on contemporary issues.

Dr. Çıdam pointed out that the Gezi Resistance shook the belief in the "invulnerability of the AKP hegemony" to its core. She emphasized that even after more than a decade, the AKP still perceives Gezi as a significant threat.

'Gezi protests marked a significant turning point'

Firstly, I would like to ask about your seminar titled "Remembering Gezi After Ten Years: The Possibility of Resistance, Memory, and Future Struggles." Why is it important to remember Gezi?

As I attempted to emphasize in the seminar, the Gezi protests marked a significant turning point for the AKP regime. Until then, the regime had defined itself as a democratic movement deriving its power and legitimacy from the people, against the entrenched elites within the state.

The Gezi protests, which can be described as the most extensive and prolonged street demonstrations in the history of the Republic of Turkey, not only challenged the populist/democratic image the regime had drawn for itself but also fundamentally shook the belief that the AKP hegemony was invulnerable. The government's harsh and repressive response to the democratic demands during these protests went beyond tarnishing its established image; it also undermined the notion that the AKP's dominance was unassailable.

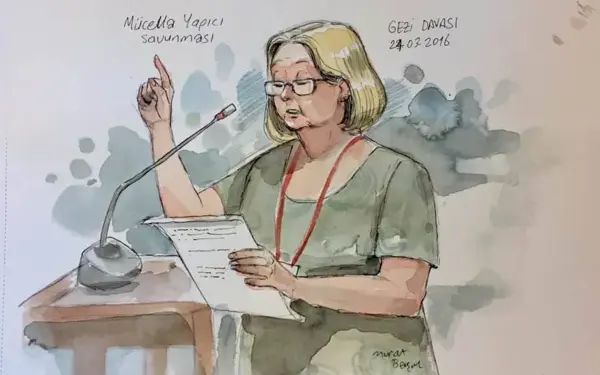

Therefore, despite more than a decade passing since the events, the increasingly authoritarian AKP regime still regards Gezi as a significant threat. The regime attempts to neutralize this threat by rewriting history. Over the past decade, we can understand the systematic effort of the AKP regime to portray the Gezi protests not as a spontaneous popular uprising but as a conspiracy orchestrated by external forces. A crucial part of this systematic effort is reflected in the convictions of individuals such as Osman Kavala, Mücella Yapıcı, Hakan Altınay, Tayfun Kahraman, Can Atalay, Mine Özerden, and Çiğdem Mater, who have been charged with attempting to "overthrow the government."

GEZİ PARK TRIAL

Turkey’s top appeals court upholds Osman Kavala’s life sentence

The regime, relying on the claim that Gezi was organized by a handful of people and with a conviction decision of highly debatable legality, attempts to both control the democratic potential of Gezi and send a deterrent message to any meaningful opposition against the ongoing authoritarian transformation in the country.

At this point, it is crucial to repeatedly emphasize that Gezi was a spontaneous, democratic movement where thousands of people took to the streets to express their constitutional right to protest and voice democratic demands. Remembering and expressing what we experienced is not only an important political stance but also a duty for anyone aspiring to a democratic society.

'The protests did not come out of the blue'

After all this time, Gezi has actually turned into a dream for the people. You also mention in the seminar that our memory is being attempted to be erased. Sometimes, I hear people say things like: "If something didn't happen in Gezi, it won't happen now," "There won't be anything like Gezi again." How do you evaluate this?

There are two issues we need to emphasize here. The first one is related to how we remember the events. Many commentators supporting Gezi described the events with an imagery of a suddenly emerging, unexpected societal explosion. I believe this imagery is problematic because it hinders us from seeing the societal formations and activism that make such protest movements possible.

When we disregard these formations, it becomes inevitable to perceive the events as extraordinary, even miraculous. While there is no doubt that the Gezi protests seemed to emerge suddenly for many of us, contrary to the widespread narrative, the protests did not come out of the blue. What made the spontaneous movement of thousands of people possible in Gezi was a series of new political habits created by previous political struggles, altering the conditions for the existence of new forms of resistance.

I consider this to be very important because saying 'spontaneous' doesn't mean sudden or instantaneous; it means acting with one's own will. The experiences and practices of many societal formations that already existed were what made Gezi possible

To give just a few examples; in the years before Gezi, environmental activists had developed a series of different resistance practices, many of which were embraced by the protesters in Gezi. Among these practices were setting up tent camps, creating human chains to stop construction machinery, and reopening previously privatized areas for common use.

Similarly, the neoliberal urban transformation projects initiated by the government, which displaced thousands of people in Istanbul, had led to the emergence of numerous grassroots movements organizing frequent protest demonstrations even before Gezi.

Finally, both the women's rights movement and LGBTQ organizations had increased their participant and supporter numbers and intensified their opposition activities in response to growing pressures, particularly since the early 2010s. Thanks to the existing political accumulations and habits, in the early hours of May 31, 2013, in response to the violent removal of a handful of activists from the park, thousands of people were able to take action with their own will and unexpected speed and solidarity.

In other words, Gezi showed us the importance of ongoing activism, the possibility of solidarity among groups that may seem different and seemingly lack a common ground, and that when we come together, we can achieve things we thought were impossible.

'So much effort into erasing Gezi from our collective memory'

In this sense, Gezi is not a miraculous, never-to-be-repeated experience but rather evidence that there is always a possibility of it happening. This is precisely why the AKP regime puts so much effort into erasing Gezi from our collective memory and, consequently, increasingly limits the space for social opposition.

The second issue is the impact of the increasingly restricted critical space on political activism. The fact that we are living in a much more repressive period than the Gezi era cannot be denied. The regime not only significantly limited the exercise of the legal right to protest but also questioned the legitimacy of taking to the streets for demonstrations – of course, we cannot overlook the role played by the flawed politics of the main opposition party, especially in attempting to reduce democracy merely to elections. We must consider the cancellation of the planned rally at Tandoğan Square in Ankara on January 14 by the Republican People's Party (CHP), citing "we will mourn our martyrs," within this context. In democratic regimes, such rallies provide an opportunity for the public to come together, mourn their common losses, and hold those responsible for these losses accountable.

In such an environment where people's constitutional right to protest is actively hindered, sustaining social activism is indeed extremely challenging. Nevertheless, it is abundantly clear that there is a protest culture in Turkey that cannot be easily erased.

Otherwise, it will not be possible to understand the ongoing movements in the streets. Whether it's the women's movement that still fills the streets, the LGBTQ organizations whose actions are repeatedly halted with police violence despite exercising their constitutional right to protest, the determined stance of the Akbelen community in their years-long struggle, the persistent and effective actions of the Saturday Mothers who are not allowed to gather in Galatasaray Square despite a Constitutional Court decision, or the resistance at Boğaziçi University that has been ongoing for more than three years, despite all the pressures.

It is through the persistent, unyielding, and unwavering societal opposition that continues to exist despite all kinds of pressure and intimidation that I believe there is no room for despair. Gezi, as an important source of inspiration for future democratic struggles, continues to endure in our collective memory thanks to this resilient social opposition.

'Gezi a source of inspiration and a reference point'

In your seminar, you mention that Gezi's reputation is under attack on every occasion. How do you evaluate the impact of these attacks? In this context, the 'Possibility of Future Struggles' is also affected. How do you assess this situation?

Undoubtedly, the AKP regime, utilizing every possible means at its disposal, consistently attempts to portray Gezi not as a grassroots movement but as an illegal "coup" attempt orchestrated by external forces, organized by a handful of people, and aimed at undermining the constitutional order and overthrowing the government.

The Gezi trials and the unjust convictions that arise from this unlawful process, as I mentioned before, constitute the most significant building blocks of this fantastical narrative. It is not surprising that this official narrative finds acceptance in certain segments of society. What is truly surprising is that, despite the regime mobilizing all its propaganda tools, it has not been able to erase Gezi as a democratic grassroots movement from our collective memory until now. This can only be explained by the persistent struggles.

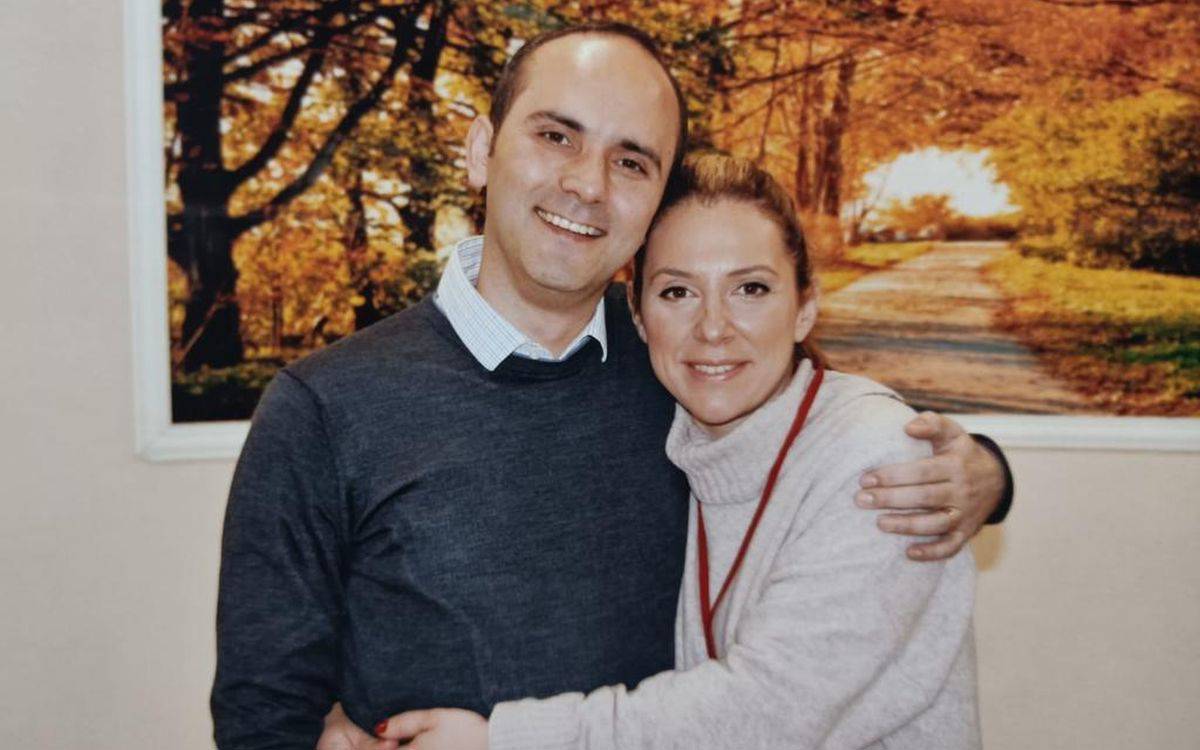

INTERVIEW WITH GEZİ PARK CASE CONVICT KAHRAMAN'S WIFE:

His wife wants everyone to join her in asking what the criminal act of Tayfun Kahraman is

Despite all the efforts of the regime, Gezi has become not only a source of inspiration but also a shared reference point for social opposition. Therefore, the political struggle over how Gezi will be remembered will undoubtedly continue for many more years.

I believe this struggle is not only crucial for the past and present but also for our future because how we remember Gezi will be one of the factors determining whether we can continue our dream of building a democratic, pluralistic, and human rights-respecting society.

Continued detention of Can Atalay

What do you think about the fact that Can Atalay, a member of the Parliament from the Turkey Workers' Party, is still in custody despite Constitutional Court decisions, ten years after Gezi?

The continued detention of Can Atalay despite Constitutional Court decisions is the culmination of numerous legal violations throughout the trial process. Beyond that, it signifies a situation where the construction of a regime that completely disregards our constitutional guarantees has been declared as completed.

Court of Cassation: 'Constitutional Court's violation decision for Atalay has no legal value'

Turkey faces judicial crisis as high courts clash over jailed MP

It is also clear that we didn't come to this point suddenly. In fact, the starting point of Gezi was a reaction against the executive branch acting unlawfully, disregarding existing court decisions. The activists intervened when attempts were made to demolish the park despite a court order to halt.

Since that day, despite the regime's increasingly lawless practices, there is still a significant social opposition striving to stand against these practices and defend equal citizenship rights. The struggles against the government's decision to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention, the resistance in Akbelen, and the legal battles waged by LGBTQ groups against illegal obstacles are just a few examples of this ongoing resistance.

Unfortunately, we cannot say the same for many opposition parties. Except for the DEM Party and its predecessors, opposition parties have failed to respond adequately to the legislative and executive branches that have refused to implement the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights in the cases of both Osman Kavala and Selahattin Demirtaş. The role of these opposition parties has been significant in reaching the current situation.

Nevertheless, I believe that the current situation is crucial in showing a fracture within the regime, and there is a significant responsibility on all parties in the Parliament that define themselves as opposition to address this.

In other words, opposition parties will either allow the regime to completely abandon its claim to be a democratic constitutional state of the Republic of Turkey, or they will learn from the ongoing societal opposition that has persisted despite all pressures since Gezi and, together with the public, put a stop to lawlessness and the destruction of the constitutional order. I hope that, especially the main opposition party, along with all opposition parties, fulfills this significant duty entrusted to them. (AD/PE)