After more than a decade of war, conflict, and upheaval, 2025 marked a turning point for Syria. The collapse of the Assad regime, the establishment of an interim government, and the lifting of long-standing US sanctions left millions of Syrians cautiously hopeful. Among them are the roughly six million who fled during the war, now grappling with the question of what the future holds—and whether it includes returning home. For many, years of displacement have transformed both their sense of self and the very idea of home.

Yaman, a 31-year-old from Aleppo who has lived in Lebanon and Turkey since 2012, is among those reflecting on what comes next. The years away have fundamentally reshaped him, yet his connection to his homeland remains strong. “Syria is entering a completely new phase in every sense,” he says from a rooftop in İstanbul’s Cihangir district. “It’s challenging, both for individuals and the government. But Syrians are optimistic, and I see on social media how motivated they are now—in a way that wasn’t possible under Assad’s regime.”

A collapsing world

Yaman remembers his childhood in Aleppo as idyllic. “I grew up in such a multicultural neighborhood—there were Christians, Muslims, Kurds, Arabs, and Armenians. Aleppo was a true melting pot with different cultures and faiths living side by side.”

But those halcyon days ended abruptly shortly after his eighteenth birthday. “Starting in 2011, just after the Arab Spring, people began demanding change,” he recalls. “An end to terrible economic conditions, soaring living costs, and a lack of opportunities.” He joined protests, carrying flowers in front of the soldiers. But the military was quick to react. Protestors were shot on the front lines.

His father, Imad—who had experienced war in both Syria and Lebanon in the 1980s—recognized the danger and knew things would only get worse. Within two days, the family packed what they could and left for Beirut. Since Yaman was eighteen, he faced the added peril of being drafted at any checkpoint, making the escape especially dangerous. And yet, he says, he wasn’t scared—just anxious. “My world was collapsing so quickly, and I wasn’t ready. Leaving friends, my home, my entire life in a matter of days—it was overwhelming.”

A rocky start

After arriving in Beirut, Yaman felt depressed and angry, struggling to accept his family’s uncertain future. Yet the very next day, he ventured out to network and look for work. “I wanted to stay active,” he remembers. “Speaking English and some French helped a lot. It was an incredibly difficult time, but I was learning a lot and felt my horizons expanding.”

Determined to complete his education, he re-enrolled in high school. Although he’d finished his studies in Syria, the war had cancelled his final exams, leaving him without a certificate. Once back in the classroom, he excelled and even received a scholarship to attend university—but not everyone celebrated the success. “Some students questioned why a Syrian should receive a scholarship in Lebanon,” he says, his face clouding at the memory. “I was even physically assaulted. It was my first real taste of backlash against Syrians, which only grew as the war dragged on.”

While many Lebanese were warm and welcoming, others—particularly Assad supporters—were openly hostile. “Sometimes people would tell us to ‘go back to your country.’ Others acted as if we were responsible for the war. My mother was deeply affected by this, especially when people treated us with pity. And after the incident at my school, she no longer felt safe in Beirut.”

Encouraged by relatives already in Turkey, Yaman's family relocated in Jul 2013 to the southern port city of Mersin, hoping to pursue Turkish citizenship through ancestral ties to Mardin, a province on the Syrian border populated by Turkey's domestic Arab and Kurdish communities. There, he returned to high school for the third time, and after graduating, enrolled in an English-speaking university—only to discover it was a fraudulent institution that targeted refugees. His diploma was worthless. Devastated, he considered trying to reach Europe.

“Over forty of my friends went. Some by small boats, some on foot. A few made it and built new lives there, but it wasn’t easy for anyone.” In the end, Yaman decided it wasn’t the path for him. “I wanted to do things properly, legally,” he emphasizes. “Being smuggled was too risky—such high stakes to arrive in another foreign land, still displaced, still searching for home.”

Putting down roots

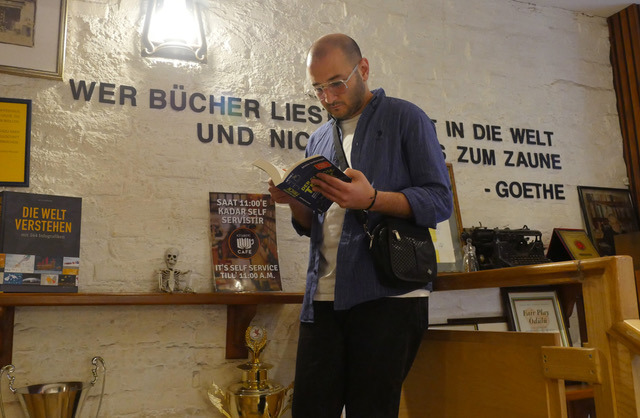

It wasn’t until two years in Turkey, after his family moved to İstanbul, that he felt he could begin building a more permanent life. Whether it could ever feel like home, however, was still uncertain. Istanbul gave him a sense of possibility that Mersin hadn’t, and he thrived in its international, fast-moving environment, quickly finding work in textile export and speaking English, Arabic, and Turkish daily. During that time, he formed close friendships with Erasmus students and other expats, relationships that helped shape his “in-between” sense of identity and belonging. “I really liked the way my European and American friends thought, their punctuality, their openness. Being around them made me reflect on who I was and where I belonged.”

Then Covid-19 struck. Yaman’s export clients disappeared overnight, a university scholarship fell through, and many of his international friends returned home. When post-pandemic life slowly resumed, he felt lost and without direction, and considered resuming the education that had been repeatedly interrupted—perhaps in Germany. But then a new era began for Syria, and his life took an unexpected twist.

A homecoming

The idea of returning to Syria had seldom crossed Yaman’s mind during the years he’d been away. The country had been unsafe, its economy in ruins, and going back simply hadn’t been an option. But after Assad’s fall and the rise of a new democratic government, he began to see and hear of more and more Syrians making the journey home. It was time, he felt, to see it with his own eyes. So in Nov 2025—more than thirteen years after leaving—Yaman returned home. His eight-day visit began with a short flight to Gaziantep, followed by a 40-minute taxi ride to the Syrian border.

“I was so anxious about the safety of the trip, and what I would find when I arrived,” he recollects after returning to Istanbul. “I was fearful of what the country would look like, and unsure how the Syrians who stayed would act and feel.”

But his unease dissolved almost immediately. Crossing into Syria was like a homecoming—a celebratory atmosphere where immigration officials treated him like long-lost family. Even the new Syrian army greeted arrivals with smiles and waves—an astonishing contrast to his memories of the old regime. But once he caught sight of Aleppo’s northern countryside, a different reality emerged. The empty streets, widespread destruction, and charred remnants of displacement were sobering evidence of the deep scars left by years of war.

On entering Aleppo proper, however, he was filled with unexpected familiarity and comfort. The neighborhoods, markets, and corners where he had spent his childhood remained. But even more surprising was hearing the locals expressing their opinions after years of fear.

“People were speaking freely, discussing politics openly,” he says, still astonished. “Before, we couldn’t even think these thoughts.”

During his visit to both Aleppo and Damascus, Yaman witnessed a country buzzing and in transition—with markets reopening, historical sites being restored, and locals filled with cautious optimism. “Life is not yet fully rebuilt—electricity cuts, construction, and bureaucratic challenges persist,” he explains. “But the sense of hope was palpable.”

The trip dissolved old bitterness—over opportunities lost, plans derailed, and the life he might have lived. Now, he is filled with excitement for Syria’s future and hopes to return soon to explore job opportunities, possibly in the diplomatic sector where his language skills can be put to use. Although his sense of belonging remains divided between Aleppo and İstanbul, his heart is beginning to lead him home.

“The future of Syria is amazing, and I want to be a part of it.”

And for the six million Syrians like Yaman who fled during the war, the question remains: what does the future hold, and will they too return? Only time will reveal where home ultimately lies for those forever reshaped by exile. (TM/VK)