Photos: Nurcan Keskin

Click to read the article in Turkish

I met with Viyan in Duhok's Mam Resam camp, a two-hour drive from Erbil where I was staying. Having taken directions from the camp authorities, upon nearing the tent where Viyan was staying, I saw three women waiting for me outside, one of whom I recognized as Viyan from the bandage on her left arm.

They invited me into their tent and as we made to sit down, I saw a large teddy bear propped up in a corner and I ask Viyan about it. "It is mine," she says, "My elder brother bought it for me when I returned from captivity."

She tells me that the last time she went to the infirmary, they had run out of dressing for the wound on her left arm and she had returned without it being seen to.

Viyan rather than talk about the child she had chosen to bring with her, preferred to talk about the atrocities the Ezidis have suffered. When speaking of this, she says, "They killed our mothers and fathers" and I only later understand that she is talking about all the murdered Ezidis, not merely her own parents.

She tells me at the outset that Mizgin, who is sitting by us and who lives in the same camp, suffered even more than she herself did.

In all that she has said so far, she has always used the plural 'We' and it is only when she says, "It was not only their customs and method of prayer that I did know, I was made a mother without knowing how to cradle or wash a baby," that she uses the word 'I' for the first time.

Viyan was 14 on August 3, 2014, when ISIL in their attack on Tel Kasap, took the entire village captive. A few days later, all the prisoners were taken together to Mosul's Babus prison. A few days later, Viyan, together with her 22-year-old elder sister and other young women, was put on a truck and taken to a school in Mosul. That was the last time Viyan say her mother, who was then two months pregnant.

In the time she was kept captive in the school, one of her fellow villagers, Cilan, unable to bear what she was sure was coming next, committed suicide by slitting her wrists in the school toilet.

Viyan, her sister and the other young women were held in the school for a few weeks and were then taken to Rakka in Syria. The systematic sexual abuse that had started in Mosul continued in Rakka.

After a while, the two sisters were sent to Homs, but here, a failed escape attempt on their part led to them being separated. Viyan was taken to a police station used by ISIL as a command center and her sister to an ISIL militant's house near the station.

Viyan's sister took her own life, shooting herself with the gun belonging to the ISIL militant who had bought her and who abused her repeatedly. Viyan received the news of her sister's death from this same man, when he came to the center a couple of days later. He took Viyan from the cell she was in to his house and made her suffer the same abuse that had been the cause of her sister's death and this continued for a whole year.

Viyan once found an opportunity to escape but was recaptured by ISIL militants on the second day. After an interrogation that lasted days, she found herself in the police station she had been first taken to.

After the ISIL militant and his family died in a Russian airstrike, an Iraqi ISIL militant took Viyan to Mosul and married her under Mosul's then laws.

Cihat

Cihat was born a year later and Viyan, together with Cihat found themselves between crossfire repeatedly during the battle for Mosul, when Iraqi forces attempted to liberate the city from ISIL.

Viyan met a friend from her village while being held captive in Mosul, this friend perished during an airstrike which also killed several ISIL militants. Viyan herself was badly injured.

After a month of treatment, Iraq forces took the hospital she was in from ISIL and she was taken to the same police station with Cihat, which the Iraqi forces had taken from ISIL. She spent five months there as the battle raged, "The streets were filled with dead bodies," she tells me.

In the fifth month, following a Facebook post by the Iraqi forces, part of their efforts to reunite Ezidi captives with their families, her elder brother was able to reach her. He told her that he had had news of their parents and two sisters.

When Viyan left Mosul with her brother and her relatives to Duhok, in the Kurdistan Regional Governorate, she left Cihat behind.

"When my mother was taken captive, she was two months pregnant. I was not yet 15, my sister who committed suicide unable to take what was happening to her was 22. I did not know them. Without knowing their names, their religion, how to cradle or wash a baby, I became a mother. I cannot be a mother to a child born of them."

Viyan repeatedly tells me she does not want to know where Cihat is or who he is with. She tells me she has received no support from the Iraqi government and that the government has no programs to help women who have returned from captivity.

Viyan, deciding to leave the land of her birth behind and a new life afar, has applied to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and is waiting to be resettled in Austria. She dreams of completing her education and becoming a teacher in Austria.

Container

I ask after Mizgin, of whom Viyan had said, "More than myself, I feel sadder for her". Viyan offers to take me to meet her and we walk to the 30 square meter container Mizgin is living in.

Upon entering, I understand why Viyan said what she had. Mizgin is lying curled up, resting her face on her palm and as she makes to get up, I wonder for a moment whether she is tied to her bed with a chain. When she gets up, I am struck by how tall she is.

Mizgin asks Viyan to close the door. I understand the tension that radiates from this dimly lit thirty square meter cabin outside when I hear the conversation between the two women.

Upon Viyan saying, "Let us leave before we cause any problems for Mizgin," she puts her hand on my knee.

"Sit, sit, he is not here."

Upon Viyan asking her, "Will he come to the court," Mizgin replies in a low, tense voice, "I do not know."

After drinking the water she serves Viyan and myself, I look at Mizgin's face and see the tiredness in her eyes. Despite sitting facing us, her sight is constantly turned towards the thin line of light visible from the crack under the shut door.

Noticing her diffidence and thinking of the long road to Baghdad that lies ahead of her, on which she will have to transfer thrice, I suggest we leave after drinking the water she has given us. At this, Mizgin comes to and insists we stay.

"I do not remember the number of times I was bought and sold, sometimes more than once a day. I was also abducted on August 3, 2014, after which I was taken first to Tel Afer and then to Mosul. After being kept for 40 days in the Badus prison in Mosul, I was taken to Rakka."

"I was kept by an American member of ISIL after he purchased me from a Saudi. I was taken to Iraq and after several attempts was finally able to escape."

Mizgin was only able to enjoy her freedom for a few days. When she tried to go to the camp her husband and daughters were in, her husband refused her wish.

Mizgin tells me she has been waiting in this cabin for months for her husband to come and forgive her. She is now struggling with this situation where her husband has rejected her but has not accepted her request for a divorce either.

"My husband blames me for being taken captive by ISIL and is punishing me by refusing to divorce me. Was it I who wanted to be taken captive? Which woman would wish such a thing upon herself?"

Her husband permitted their daughters to visit her on a few occasions. I take leave of Mizgin who is preparing to travel to Baghdad the next day to file for divorce. The last sound we hear is that of the door to the cabin being locked.

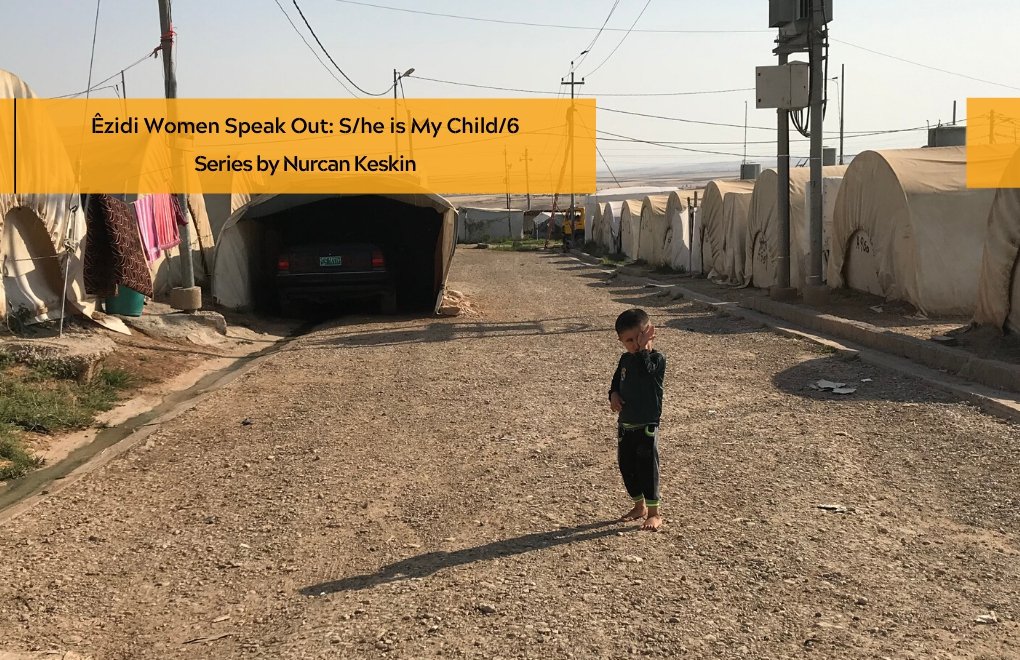

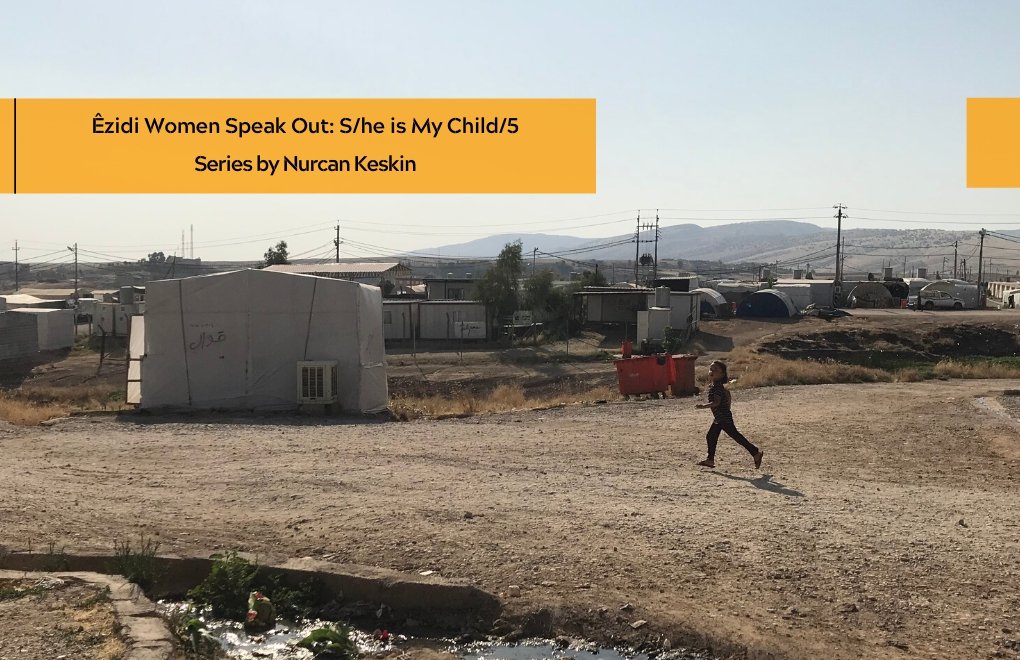

Viyan and I walk to her tent under the 39-degree heat. There are 1,704 people living in this camp but we are alone save for our shadows.

It is time to leave for Erbil and Viyan embraces me with one arm and walks away, limping with feet still raw from burns. (NK/VK)

Tomorrow: Leyla

Êzidî Women Speak Out: 'S/he is My Child'

Zozan's Family: You Have No Choice But to Give up Your Child for Adoption

Meyrem: We are Left With No Choice But to Leave for Afar

Two Sisters, Fahima and Rayan and Their Cousin Seher

Leyla: The Only Thing That Keeps me Going is the Hope to See My Son Again

The Mosul Dar Al-Zahur Orphanage

'Êzidî Women are Breaking the Mould and Remaking Their Society'