Photos: Nurcan Keskin

Click to read the article in Turkish

With the fall of ISIL, many of the thousands of Ezidi women abducted by the group began to return to their homeland in Northern Iraq. While the Ezidi community, despite initial fears to the contrary, opened its arms to these returnees, this same welcome did not apply to those of them who returned with children born of rape at the hands of ISIL members. With few exceptions, these women who returned with children have faced rejection by their families and society. These women narrate their plight here.

Give up your child!

Else do not ever return here!

This is the choice that Viyan, Mizgin, Leyla, Meyrem, Zozan, Royan have been forced to make. Over a thousand women, little seen or heard by the wider world have been confronted by this diktat upon their return from ISIL captivity to their families, "Make your choice".

These women would instead this be a matter for each women to decide for herself, but the society they have returned to has shown little sign of accommodation.

August 3, 2014

On the 29'th of June, 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL) took Mosul, Iraq's second largest city and by August 3, 2014, were in Sengal.

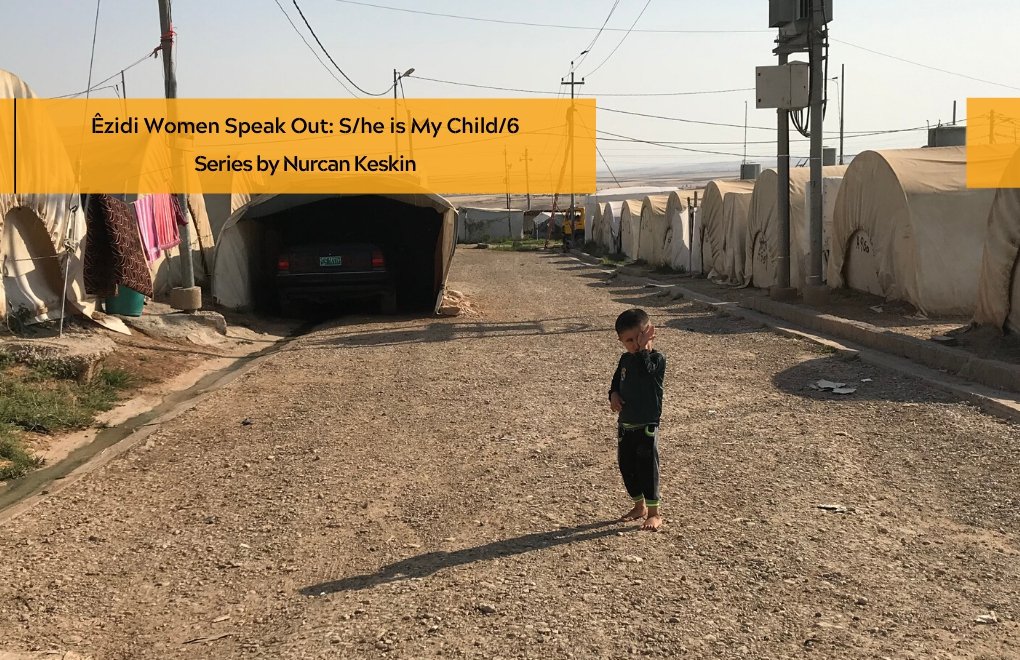

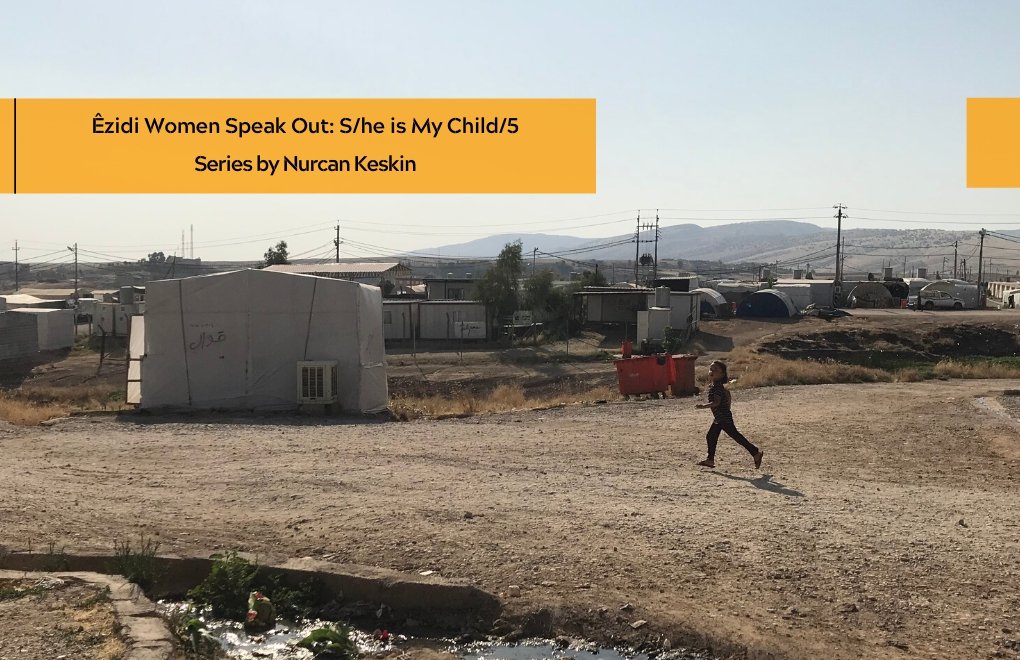

At the time of the ISIL attack, around 360,000 Ezidis were living in Sengal. In August 2018, more than 90 percent of them had been displaced, with a majority living in camps outside the region.

The ISIL invasion was a humanitarian tragedy of extraordinary proportions. It is estimated that between 2000 and 5500 Ezidis were killed, 6300 Ezidi men were kidnapped and countless women and children were used as sex slaves under a horrifying and organised system of sexual exploitation. Over a thousand children were born of rape. These figures are taken from reports compiled by international organizations working on this issue.

August 2018

In August 2018, it was estimated that over 2500 Ezidi women and children were still in ISIL captivity. Captive women were sexually abused, given as wives to ISIL fighters and sold in slave markets. Many of these women fell pregnant and gave birth during their captivity.

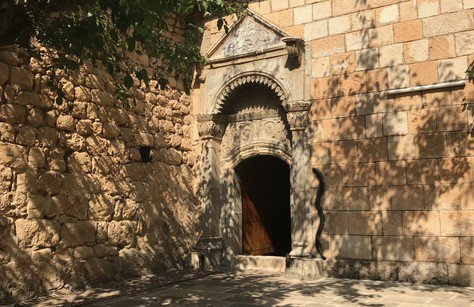

The Lalish Temple in Kurdistan region, Iraq.

The Lalish Temple in Kurdistan region, Iraq.

Starting in 2016, as the ISIL began losing territory, women started managing to escape from their captivity. In other cases, families of captive women were able to arrange for their freedom through the payment of large sums of money to their ISIL captors.

Several of the Ezidi women who gave birth to children after sexual abuse have avoided facing society, while others among then, unable to bear the constant censure and pressure have either given up their children for adoption or abandoned them. Some women after giving up their children to orphanages have sought to reclaim them but have run into insurmountable difficulties.

Lalish Temple

Lalish Temple

Between the family and the child

On April 24, 2019, the Ezidi Supreme Spiritual Council released a statement that welcomed women returning from ISIL captivity but also announced that children born to them from fathers who were ISIL members would not be accepted into the Ezidi fold. This decision, which was supported by a majority of the Ezidi populace forced returning Ezidi women, already heavily traumatized, to confront a new struggle.

Children born of Ezidi mothers and ISIL fathers are ostracized by Ezidi society and on occasion have been publicly humiliated and beaten. The mothers in turn have been forced to make an impossible choice between family and child due to social pressure.

This has led many to ask if these children will suffer the same fate as the "Unseen and Forgotten" children born of rape during the Bosnian war.

The Ezidi Supreme Spiritual Council

The Ezidi Supreme Spiritual Council in its 24 April announcement had taken the bold decision to welcome back all abducted women. This enlightened decision however led to a major controversy in the Ezidi community and the council a few days later issued a clarification that this did not extend to any children Ezidi women had mothered during their captivity.

Under Ezidi tradition, only children with both parents being Ezidi are considered as such. Further, the citizenship laws of Iraq rule that any child of unknown parentage or one of whose parents is Muslim is automatically registered as Muslim.

The second declaration was criticized by local and international groups, some of whom pointed out the irony of a Council, all of whose members were men ruling on a matter that fundamentally affected Ezidi women. Exact figures are hard to come by, but I heard from many that this decision led to a large increase in Ezidi women giving children born during captivity up for adoption at the orphanage at Mosul.

Experts and activists I spoke to indicated that one of the factors behind this second proclamation was that even if the Ezidi community welcomed these children into its' fold, Iraqi laws would register the children as Muslim, an issue that could lead to any number of legal problems and which could only be resolved by amending the Iraqi law on Citizenship and Naturalization. This is something that the Iraqi government has refused to address.

I spent nine days traveling through the camps scattered through the desert of Iraqi Kurdistan, around Duhok and listened to Ezidi women who had returned from their captivity about their sufferings, speak about their years of captivity and their lives that had been turned upside down by the war. Many of these were mere children, barely out of their teens.

After all their unimaginable sufferings, they have now to contend with the prospect of losing their children.

Leyla

Leyla, after four years of captivity, returned after her husband paid a ransom to her ISIL captor. Her husband and family refused to accept her eighteen month old child she brought back with her and she was forced to give up the child for adoption.

However, unable to bear this separation, she continues to seek a way of having the child returned to her.

Meyrem

When Meyrem was abducted from a village in Sengal, she had only been married for a few days. She gave birth to a baby girl during her two years in ISIL captivity and after her escape, stayed at the Ezidi Home (Mala Ezidiyan), where a few days later, she met her husband, who had himself only just escaped from captivity from an ISIL prison.

In a rare occurrence, her husband supported her decision to keep her child, but her family has disowned them.

Zozan

On August 3, 2014, Zozan, then just 15, was abducted together with her elder brother during the ISIL attack on Koco village.

Zozan, after years of captivity now lives with her aunt in Duhok. Six months pregnant, she poignantly says, "I was able to see my first child for just five days. I cannot bear the thought of being separated from my second."

Viyan

Viyan was abducted together with her family at age 15. At the time of the ISIL attack on their village, her mother was two months pregnant. She would never see her again.

Viyan, unlike the other women I spoke to, is clear in her resolution, "I cannot mother a child born to me of rape". After a ceremony where she bathed in the holy waters of Lalesh, she now lives with her family in a camp near Duhok.

Rayan

Rayan was abducted together with two of her sisters. There is no news from her elder sister Selime. Her younger sister Fatma, who is now in a camp near Duhok, lives in constant regret at having given up her child for adoption in Mosul. Rayan is still in Syria with her two children, at the El Hol camp.

Pressing Questions

It is not merely the radical conservatives among the Ezidis that do not wish to accept these children. Most Ezidis are of this thought and opinions to the contrary are few and far between.

Of the women who returned with children, some have moved from camp to camp to escape social censure. Some of them have managed to settle abroad, taking their children with them.

A historically closed community, the Ezidis have suffered unimaginable trauma at the hands of the ISIL. Given this background, one is led to ask the deeply troubling question, "What fate awaits these women and their children?"

Is there no recourse for these women apart from giving up their children?

Would a change of mind on the part of the Ezidi Supreme Spiritual Council change the situation of Leyla and many other women like her?

In Erbil and Duhok

In this series of articles, I'll share with you the stories of women forced to live under the weight of this pressure from four of the thirteen main camps in Northern Iraq where the Ezidis currently live. The Mosul orphanage is a key element of this story but not having a visa for Iraq, I was unable to visit Mosul. Instead, I interviewed Sakine Muhammet Yunus Ali, the director of this orphanage and at the same time, the head of the Musul Directorate of women's and children's affairs, in nearby Erbil.

Sakine Muhammet Yunus spoke about the orphanage and its' history, the children there and their uncertain future.

The final article will be an interview with a leading Ezidi activist and key figure in the humanitarian efforts in Sengal, Khidher Domle, where he discusses current societal attitudes towards Ezidi women and their children. Khidher Domle is the co-ordinator of the Duhok Women's and Children's support center, an important center that provides rehabilitation and trauma counseling services to women and children and is supported through grants from several international organisations including the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). At the same time, he is also a researcher specializing in Conflict Resolution and Peace building issues at the University of Duhok.

The series 'Ezidi Women speak out : This decision should be ours to make' will run for seven days starting Monday.

Thank you all,

Nurcan Keskin. (NK/VK)

Zozan's Family: You Have No Choice But to Give up Your Child for Adoption

Meyrem: We are Left With No Choice But to Leave for Afar

Two Sisters, Fahima and Rayan and Their Cousin Seher

Leyla: The Only Thing That Keeps me Going is the Hope to See My Son Again

The Mosul Dar Al-Zahur Orphanage

'Êzidî Women are Breaking the Mould and Remaking Their Society'