Click to read the article in Turkish / Kurdish

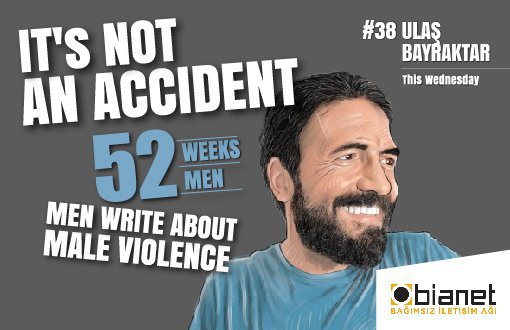

I am Ulaş Bayraktar, a 43-year-old, supposedly educated, presently middle class, married father, and I have never claimed to be a feminist.

Why?

To begin with, I am the eldest son of a woman who was widowed at the age of 33. With the privilege of being the child of a woman who raised her two sons all by herself despite her young age, first in the little town where she was born then in a big city where she had no relatives, by struggling against all kinds of bureaucratic, social and economic hardships, I have witnessed firsthand what women are capable of achieving.

Therefore, my first contact with womanhood was a mother figure who never shied away from saying and doing what she had set her mind on.

Moreover, since I grew up in a house without a father, I did not experience any husband violence or male dominance, which might have caused me to remain relatively ignorant of domestic violence. The worst incident I remember is when my mother had a row with my grandfather and we spent a few days downstairs without seeing them.

I cannot deny that my adolescence, which I went through in a foreign private school, was full of male frivolities and excesses. Looking back on those days, I only now realize that our girl friends were watching us with disdain and even pity.

Immediately a solemnity would come over our friend who had a girlfriend; while holding hands and sitting in a close embracing with his girlfriend, he would put on that cynical look and stay away from the adolescent scenes for some time.

With a seriousness and solemnity, he would show off as if saying, "May Allah save you, as well".

What opportunities we were missing in the throes of this male adolescent nonsense.

In classes, we had to read Of Mice and Men and so we imitated Lennie; after we watched the 1984, the only thing we remembered about the movie was Julia's breasts which were seen in one scene; in the Death of a Salesman, we never sensed the fate of Willy which was awaiting us; we got carried away with the boys in the Lord of the Flies.

We never gave it a thought why our teacher from the US volunteered to go to Erzincan after the earthquake and we never appreciated the exercises we did in creative writing courses, which were in fact as valuable as diamonds.

As for the girls, they were enjoying these oases created within the curriculum of Turkey.

When I went to university, I met women from the southern provinces of Anatolia, who had made the best of these oases back in the day and surprised me with their intellectual interests and knowledge.

To be able to spend time with them, I was trying to understand structuralism, reflecting on the concept of natural law in the context of international law and was discovering the meanings of the lines in Three Sisters, which we had merely memorized and staged in high school.

Our only oasis was the mountaineering club. Since we could carry heavy backpacks, go on long hikes and climb high mountains, it was only there that we could enjoy our physical superiority to women. When it came to the flexibility required for rock climbing, we were again crestfallen, but we gave up on that passion before long anyway.

When I started to work as a hiking guide in summer thanks to these mountaineering activities, I could not have known that I would come across the bearing of my life.

While she was taking the first steps in her academic career, I changed my course to a profession which I had never thought of practicing before. All of my values were filtered through her sieve now, they were reshaping and reemerging.

First, we discovered together the secrets and beauties of the Taurus Mountains and the Mediterranean, which witnessed and harbored the birth of our love. Then, the streets, cinemas and historical sites of İstanbul took on meaning one by one.

I met Paris through her eyes. We made it our home; and, then, Ada. Mersin, where we had been living since fifth grade, was now an entirely different city. In a short time, it also became a city with Umut (Hope).

A person could find his lover, his friend, his life partner, his colleague, his mind-mate and his companion in a single person, which I have also learnt from a woman.

Naturally, the women I know are not limited to my relatives, my classmates and their lovers. I have known women who suffered greatly, who were subjected to tyranny, mobbing, harassment and rape. But, only some of them had turned these experiences of violence into self-pity.

Neither were they grieving for their sorrows, nor were they escaping from life. They have derived strength and belief from these sorrows and continue to act and match wits with life in a stronger and more determined manner.

They make the best of what lies in their hands and hearts without asking for help or owing anyone; they undauntedly struggle to do their best, be that in science, arts, commerce or journalism.

Do not look for them only and solely within the organized feminist struggle. You saw them during Gezi and you continue to see them among the Academics for Peace, at the Galatasaray Square and in the highlands of Black Sea.

On the other hand, male dominance and male violence are not absent, they are even on the rise; yes. Because men are nervous. There are women everywhere, who demand to have a say in decision making, do not leave politics to men, do science, arts, journalism and management more skillfully than men, know to say no and do not refrain from saying it.

There are women who do not want to become lovers or get married, who do not live sexuality as per the men's demands, women who want to divorce, work and leave, all of which make us men nervous; we feel that the ground is slipping under our feet.

That order, which is ruled by the men who have the physical strength and opportunity of education, is now changing rapidly.

The new economic order does not really require you to be muscular or strong, but it requires that you develop creative, original ideas and projects and pursue them with patience and diligence.

It is not because they are women's professions, but because women have the creativity, patience and meticulousness required by these professions that they have better chances of being successful in this new order. Therefore, the more established this system becomes, the stronger the position of women in the new order will get.

In her study titled "The End of Men: And the Rise of Women", which appeared in The Atlantic magazine in 2010 and was published as a book in 2012, the US journalist-writer Hanna Rosin puts forward the changing balances in the gender struggle.

Rosin argues that as economy is now based on reflection and communication, rather than physical strength and endurance as was previously the case, the advantage enjoyed by men for centuries is coming to an end and women, who have social intelligence and ability to concentrate, are becoming more successful in professional life.

As a matter of fact, Rosin observes that better-educated women already make up the majority in 13 "of the 15 job categories projected to grow the most" in the near future.

I have no doubt that as this change gains ground, women will come to a more decisive position not only in economy, but in politics, as well.

Though I very much value the efforts made to speed up this change, I cannot help expressing my reservations about it at every opportunity. Because I am worried that the growing nominal presence of women in politics may not be able to effect a change in the logic of politics.

In my opinion, that the Iron Ladies, zeibeks in high-heels, Merkels, Çillers and Rices do politics does not bring about much change in the masculinity of politics.

The masculinity of the order can tend to maintain itself over "crypto" women. I frequently encounter female looking masculine politicians not only in politics, but also in civil society and even within the feminist struggle.

I cannot help but observe that a struggle waged only against men and an effort to gain rights by trying to retaliate them also masculinize women in the end.

In fact, women can wage a real struggle by making the best of what lies in their hands and hearts, in their own styles, with their own choices of action and perseverance. To me, pondering about constructing a new political habitus and making efforts to that end seems to be more meaningful than the disappearance of the word "bayan" [a derogatory equivalent of "lady/ma'am", used as a supposedly "polite" form of address as opposed to "woman" which is considered "vulgar" in some and particularly conservative circles].

Of course, I know a lot of women who view the feminist struggle from this perspective, but I think the prevailing understanding of struggle is about changing men, persuading them and demanding rights from them.

However, it seems to me that the prospective empowerment of women, which has already started, needs to be more independent of men.

Because though the success of the power struggle waged against men will change the existing injustices in favor of the female gender, it might still result in nothing but the immanent reproduction of the gender asymmetry.

In fact, a movement that would be created by further embracing women's own natural styles of thinking and acting might be the only way to establish a more egalitarian society.

Lucky me for my path has crossed with so many women who have been walking on that road. (UB/ŞA/APA/SD/IG)

* Images: Kemal Gökhan Gürses