Click to read the article in Turkish / Kurdish

I must have been in my first year of junior high; I remember I had my black school bag in my hand. It was winter. Dusk was about to fall. The streets were filled with students and government officials all done for the day. It was not raining, but that sticky, humid air which never left the city had become even more dense.

I was on Trabzon's most crowded avenue, in the middle of Uzun Street—somewhere between Mehmet's Bookshop and Saray Cinema—when a man walking in front of me suddenly leapt into motion, taking out a stick—or maybe it was an iron bar, I could not tell—from under his thick coat and slammed it on the back and then the head of a young man in parka a few steps ahead of him.

As the poor bloodied man collapsed in a heap, the other ran away. A buzzing crowd gathered with startling speed around the young man whose head was already laying in a pool of blood. Having so closely witnessed such a horrific event, I was overcome with palpable terror and excitement.

People started trying to lift the motionless body while I continued to stare, curious. As I was pushed back by the erratic crowd that flooded the "crime scene", I lost sight of the young man whose head was split open and I ran away from there.

What thrilled me so, I have to admit, was my sudden privilege of coming by a horrific and bloody story. I had laid claim to be the witness of an awful murder (he might not have been dead, but that did not matter so much at that moment).

I sprinted down the rest of Uzun Street and darted into my father's cigarette-smoke-filled shop on the Square completely out of breath (My father had a shop where he sold spare car parts, which was located on the Square across from the municipality building, and frequented by his garrulous hunting buddies).

The seven or eight regulars inside turned their heads to take a glance at me and then resumed their interrupted conversation.

Frankly, I was pleased with their indifference, unwilling to betray my fear from the first—my knees were still shaking slightly—but I also felt this unstoppable urge to tell them about the incident of the split head that I had just witnessed.

That being said, the horde was uninclined to pay any attention to me as they listened to the story my father was telling probably for the hundredth time and always with the same verve. The topic was a large bear my hunter father had shot around Van a few months ago.

Shooting the bear that he had been following for a long while, reaching the high, steep rock where he got stuck in his crawl, skinning it there, and taking out some of its inner fat prized for its medicinal qualities, had been such a tall order and taken him so long that it had gotten dark by the end.

It had been very dangerous getting back from that steep cliff and the screes in that darkness, with his Mauser rifle in hand and the bear's hide weighing on his back, but he did not have another choice. In the end, after averting quite a few dangers, as well as falling over twice and spraining his ankle, he had made it to his car (My father had a green Skoda then).

This adventure led to others, to different hunting stories amidst heated cries, and I lost my appetite to tell the story of the split head. I kept on listening to that rowdy conversation from a corner.

After a while the door opened and a lottery seller came in. I can vividly picture that moment and my own astonishment in it. The lottery seller was a skinny woman looking all the more feeble in a thin beige overcoat that was too big for her.

With the white cap that said National Lottery on the red band on its visor, which she wore over her tightly wound headscarf, she was standing at the door, lottery tickets in her hand, staring at that strange assembly of men.

Their excitement brought to a sudden halt, the men looked at the woman for a short while and then turned their heads away to pick up where they left off in their impassioned hunting stories.

I, on the other hand, could not tear my gaze away from the white nylon cap sitting so pitifully atop the woman's head, and felt ashamed.

I felt truly ashamed by the woman's so suddenly materializing presence that disappeared as suddenly under the gaze of that horde, and by that white cap. I felt ashamed in a way I could never explain to myself. I felt so ashamed I could die.

The woman just stood there for a while without saying anything, and then she silently turned and left.

Some time after she left, the crowd dispersed amid laughter. On the way home I told my father my bloody murder story that I had witnessed.

He did not react as strongly as I thought he would.

We picked up bread from Rüştü's bakery. The rain had started by the time we got home. (TP/ŞA/APA/PU/IG)

* Images: Kemal Gökhan Gürses

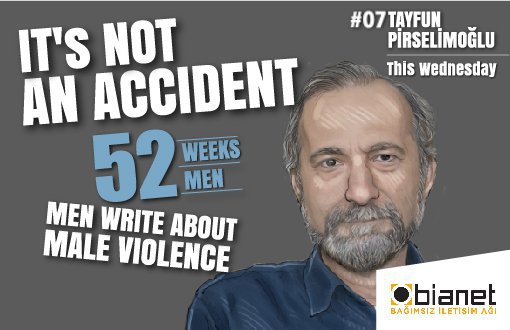

CLICK TO READ ALL "52 MEN 52 WEEKS" ARTICLES

|