Click to read the article in Turkish

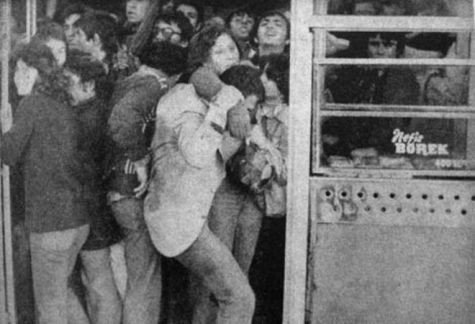

"Though I don't know the exact circumstances under which he fell, I could never shake the image of that crowd, the smoke, and my father's back being crushed. But for years I felt this pain in my back—because that's how they killed my father, by trampling on him and crushing his back."

This is how Birsen Kement, who lost her father on 1 May 1977, expresses her grief. Her father was 41, she was just 17.

Birsen Kement was the first person I interviewed. Although her father's story had appeared in other platforms, we never knew her own experience in such detail. As I listened to her, I felt the sorrow and the tension inside me grow. These feelings stuck with me throughout the interviews.

Contacting friends and relatives

Of course I knew what happened on 1 May 1977 from my readings about recent Turkish history. I knew that dozens of people were helplessly crushed, that some were executed, or rather murdered, on the spot.

Before beginning this research, I would regularly scan the websites and archives of leftist organisations. I would read about 1 May 1977. After all, it was something that had happened over forty years ago. How difficult could it really be? Extremely difficult, as I would come to find out.

When beginning the research, I set myself a goal: I was going to contact the friends and relatives of ten of the people who lost their lives that day. Over the 43 years that had passed, five families had been contacted, so ten didn't seem a particularly challenging goal. Psychologically, achieving this goal would comfort me, or, at least provide me with a little solace.

Connections

With the connections I had established over the years, I made use of all the relevant associations, unions, and political parties, as well as the people around me. I began investigating the lives of those who had died by asking for support in my endeavour from the people I knew and trusted.

There were teachers, medical staff, and students who had been massacred. I called my friends who were lawyers, educators, doctors. There was one great source of uncertainty for me: Exactly who were those who lost their lives on 1 May 1977? There was a possibility that I would fail to reach anyone at all, and this possibility frightened me.

Given the political atmosphere of the time, and especially with the propaganda in the centre-right press declaring it dangerous to go out on that particular 1 May, I thought it wouldn't have been possible for people to have been in Taksim Square unless they were with an organisation.

I thought, therefore, that union archives might contain information about the people who were there that day. Maybe their friends, the people they worked with back then, were still unionists. Most importantly, they had to have relatives who were still alive. This was one of the areas in which I felt the most helpless.

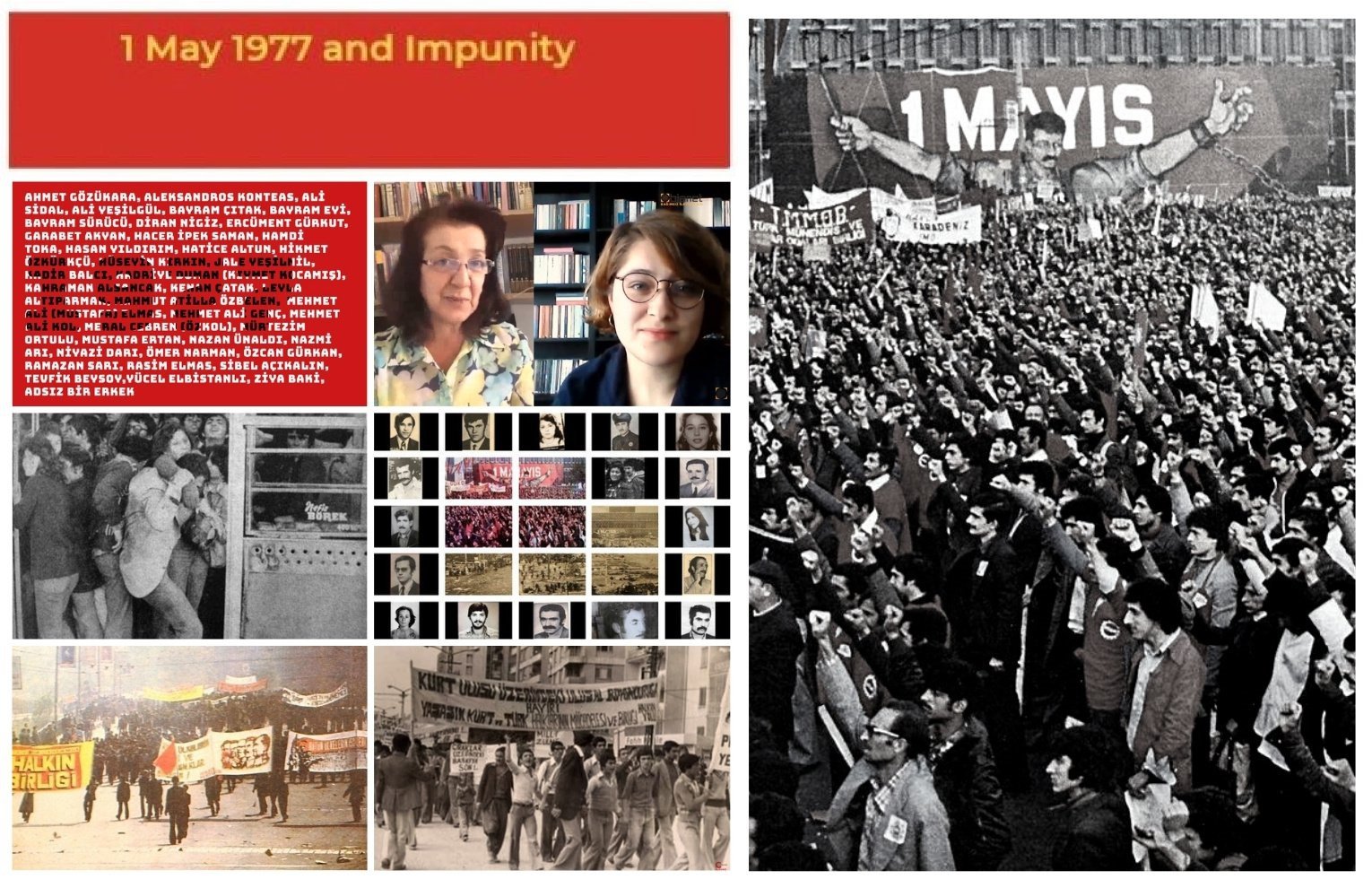

27 lives

Now, on 31 December, we are completing the process I began in March 2020. But it is a process that remains open-ended. I say this because some of the families of the 34 people who were massacred did not wish to speak, and for some I was unable to find any trace of them at all.

The number of those who lost their lives reached 41 in the new list made by Fahrettin Engin Erdoğan from the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey's (DİSK) in 2010. There is still no information about those who were added to the list in 2010, other than their names.

Therefore, in the hope of completing the stories of all who died that day, our call to friends and relatives remains open.

I was able to reach the friends and relatives of 27 of those who lost their lives on 1 May 1977. Not on my own, of course. I would like to express my gratitude to Nadire Mater, who stood by my side throughout the research, encouraged me and reignited my hope each time I fell into despair, who opened up such a plethora of opportunities for me, by activating all her connections, and by coming up with the idea of the project in the first place.

My age

On a personal level, I witnessed the surprise some felt at me conducting research about a time when I hadn't even been yet born. This surprise was expressed by the families of those who died, and I also encountered it on social media.

Let me give you a couple of examples: "You're the same age as my child," "I have grandchildren your age," "You're younger than my daughter." I don't know if such reactions served to motivate me further, but it definitely made me happy that my age wasn't considered a disadvantage.

The relatives and friends of those who lost their lives, most of whom were being contacted for the first time, said they were grateful to me for "undertaking such a task at such a young age." But in fact it is me who would like to express my gratitude to them.

Knocking on doors

While interviewing relatives and friends, my most explicit observation was this: In most cases, no one had ever come knocking on their door, and this had led to a sense of resentment. But despite this resentment, they still wanted to talk.

They wanted to talk because speaking, telling these stories, was therapeutic for them. In the case of families whose loved one had been part of an organisation (particularly those who were with the Alliance and Solidarity Association of All Teachers [TÖB-DER]), the unions and organisations their loved one was affiliated with had taken a keen interest in them, and done everything within their power to help those left behind to carry on with their lives.

But others had had to bury their loved ones and tackle the hardships they faced alone.

Impunity

Every time I reached a new friend or relative, my excitement grew. Over the course of the project, I also established a real bond with each of them. I now know by heart all their names, ages, occupations, and where they were from. However, towards the end, I realised that this process had taken a psychological toll on me too.

The level of impunity in the case of this massacre that dates back 43 years shook me to my core. Just like us, the families were also unaware of the status of the legal proceedings concerning this case. Most didn't even have autopsy reports. The reports either had never been given to them or had at some point been lost.

What's more, even the lawyers who followed the court case couldn't provide me with answers. Some were no longer alive, and some were too unwell to speak.

Lost files

Most unions and organisations lost the files in their archives following the 1980 military coup; therefore, the only sources at my disposal were old newspaper reports. The case file had been handed over to the Martial Law Court in 1978. And you know what happens after that.

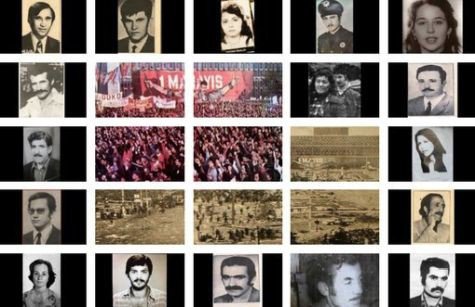

This report ends here, but it remains open to new information and new developments. We now know why 27 of the people killed were in Taksim that day, we know about the lives they led, the jobs they did, what brought them joy.

To me, and I know to many others as well, this is invaluable. These individuals, for the most part, will no longer be remembered merely as numbers. Their short lives stand before us, along with their children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren.

Autopsies

These people were not merely the numbers that appeared on the autopsy reports. If I have played some part in rendering them more than just numbers, if friends and relatives have found some comfort in recounting their loss, then I can find some happiness in this myself.

Now all I want is for those responsible for this massacre, as well as those who have been protecting them, to face justice. Because I know that if the perpetrators of 1 May had been tried, Turkey might have been a different country afterwards.

Had they faced justice, perhaps our friends would not have been killed so easily in Ankara on 10 October 2015, or at least their murderers too would have been put on trial. Because I know that the state of impunity brings nothing but more suffering. (TY/APA/VK)

Those whose friends and families we were unable to find Aleksandros Konteas (57, Labourer) Istanbul-Fatih Ramazan Sarı (11, Student) Istanbul-Küçükçekmece Leyla Altıparmak (19, Nurse) Diyarbakır The DİSK list Ali Yeşilgül, Bayram Sürücü, Mehmet Ali Kol, MUstafa Ertan, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı. |

|

| This text was created and maintained with the financial support of the European Union provided under Etkiniz EU Programme. Its contents are the sole responsibility of "IPS Communication Foundation" and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. |

CLICK - 1 May 1977 e-book is online

The ones who lost their lives on 1 May '77The ones whose loved ones we could talk to: Ahmet Gözükara (34, teacher), Ali Sidal (18, worker), Bayram Çıtak (37, teacher), Bayram Eyi (50, construction worker), Diran Nigiz (34, worker), Ercüment Gürkut (27, university student), Hacer İpek Saman (24, university student), Hamdi Toka (35, Seyyar Satıcı), Hasan Yıldırım (31, Uzel worker), Hikmet Özkürkçü (39, teacher), Hüseyin Kırkın (26, worker), Jale Yeşilnil (17, high school student), Kadir Balcı (35, salesperson), Kıymet Kocamış (Kadriye Duman, 25, hemşire), Kahraman Alsancak (29, Uzel worker), Kenan Çatak (30, teacher), Mahmut Atilla Özbelen (26, worker-university student), Mustafa Elmas (33, teacher), Mehmet Ali Genç (60, guard), Mürtezim Oltulu (42, worker), Nazan Ünaldı (19, university student), Nazmi Arı (26, police officer), Niyazi Darı (24, worker-university student), Ömer Narman (31, teacher), Rasim Elmas (41, cinema laborer), Sibel Açıkalın (18, university student), Ziya Baki (29, Uzel worker), The ones whose loved ones we did/could not talk to: Aleksandros Konteas (57, worker), Bayram Sürücü (worker), Garabet Akyan (54, worker), Hatice Altun (21), Leyla Altıparmak (19, hemşire), Meral Cebren Özkol (43, nurse), Mustafa Ertan (student), Ramazan Sarı (11, primary school student) The ones only the names of whom are known: Ali Yeşilgül, Mehmet Ali Kol, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı The one whose name is unknown: A 35-year-old man |

The voices of those who lost their loved ones: 1 May '77 and impunity

Political panorama of Turkey-1977

Film industry worker Rasim Elmas, 41, died in Taksim

Construction Worker Bayram Eyi, 50, died in Taksim

Teacher Bayram Çıtak, 37, died in Taksim

High School Student Jale Yeşilnil, 17, died in Taksim

Teacher Kenan Çatak, 31, died in Taksim

Teacher Ahmet Gözükara, 33, died in Taksim

Teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü, 39, died in Taksim

Student-laborer Niyazi Darı, 24, died in Taksim

University student Nazan Ünaldı, 19, died in Taksim

Teacher Ömer Narman, 31, died in Taksim

Laborer Ali Sidal, 18, died in Taksim

Counterperson Kadir Balcı, 35, died in Taksim

Student Hacer İpek Saman, 24, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Kahraman Alsancak, 29, died in Taksim

Laborer Hüseyin Kırkın, 23, died in Taksim

Student Ercüment Gürkut, 26, died in Taksim

Public order police officer Nazmi Arı, 26, died in Taksim

Laborer Mahmut Atilla Özbelen, 26, died in Taksim

Factory worker Hasan Yıldırım, 31, died in Taksim

Itinerant salesperson Hamdi Toka, 35, died in Taksim

Security Guard Mehmet Ali Genç, 60, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Ziya Baki, 30, Died in Taksim

Laborer Mürtezim Oltulu, 42, Died in Taksim

Teacher Mustafa Elmas, 33, Died in Taksim

Student Sibel Açıkalın, 18, died in Taksim

Laborer Diran Nigiz, 34, died in Taksim

1 May 1977 & Impunity

'The state is implicated in this crime, perpetrators must be put on trial'

'If you can't find the killers, you can't remove the stain'

'The perpetrators of the 1 May 1977 massacre got away with it'

Remembrance as a matter of dignity and the fight against impunity

Who is hiding the truth and why?