and so castles made of sand, fall in the sea, eventually **

Jimi Hendrix

Click to read the article in Turkish / Kurdish

The beginning of gender studies in general terms coincides with the beginning of the twentieth century. This beginning can be attributed, on the one hand, to the advent and rise of feminism as a social movement in the west and, on the other hand, to the emergence of discussion and research on sexes in social sciences and particularly in early anthropological and psychoanalytic studies.

As of the 1960s and 1970s, these discussions took on a critical dimension with the world shattering effect of second-wave feminism—and that of LGBTQIA+ studies in the years to come—and have developed as gender studies.

Feminist criticism, especially with its emphasis on "personal is political", became so influential that the subjects, which used to be ignored and refrained from being addressed in the academia and social movements, started to be discussed both in academic studies and also within the political struggles that were forcing the daily life to change.

Such that, men had to give answers. As a reflection of this, especially as of the late 1970s, studies on men and masculinities began to emerge as a new field of gender studies in the academia.

***

When we look at gender studies in general, I think that we see two—complementary—paths: The first one is the analysis of gender with a focus on differences. These differences are not solely limited to differences of gender identity and sexual orientation or cultural differences between (heterosexual) men/women and LGBTQIA+ individuals.

For instance, as it has been emphasized by Raewyn Connell, one of the founders of critical studies on men and masculinities, masculinity is not universal, essential, divine and/or unchangeable.

The existing state of masculinity does not stem from biological reasons. This state varies on the basis of historical, cultural and social differences as well as sexual orientation, ethnicity, class and physical characteristics. Moreover, it can change and can be changed.

In the second path, gender is addressed with a focus on power relations. Gender is an area of relations shaped by patriarchy and (hetero)sexism. This second approach focuses on the criticism of male domination and discrimination based on sex and sexual orientation.

For instance, LGBTQIA studies have underlined that homophobia/transphobia is not a fate. As for feminists, they have opened male domination, gender inequality, misogyny, violence against women and derogatory discourses against women as well as patriarchy itself to discussion and emphasized that these can be changed.

(However, apart from these two basic lines, it should be noted in parentheses that there are also the ones who embrace and/or advocate the status quo despite discussing gender. Additionally, there are those who talk about gender in a way that could eliminate the critical potentials of the concept.)

***

As I have mentioned above, studies on men and masculinities have emerged as a response to feminism, and LGBTQIA+ studies.

These studies were not critical for they opened men and masculinities to discussion solely within gender studies. These studies that opened masculinities to discussion did not have to be critical for they only discussed gender.

From the very beginning, there has been a line in the field, with supporters especially in the US, claiming that masculinity has been lost (!), arguing that men have suffered losses (!) and crises of masculinity due to feminism (which they always criticized), and stating that masculinity should go back to its essence which is essentially good (!).

On the other hand, there has also been a line that has kept a clear distance from feminists since the very beginning and made the criticism that masculinity has harmed men the most (!) and has caused the biggest damage and destruction to men (!).

However, there has developed a third line that has become a more powerful and richer vein over the last forty years, namely "masculinity studies" which approaches men and masculinities from a "(pro)feminist" and "anti-sexist" perspective and has now come to the fore rather with its critical aspect. Following in the footsteps of Jeff Hearn and with the aim of underlining the emphasis on criticism, I prefer calling it "critical studies on men and masculinities".

The concepts of "hegemonic masculinity" and "masculinities", which were put forward by Raewyn Connell and are frequently misused, have now become a hallmark of the field.

The concept of "hegemonic masculinity" emphasizes that under certain socio-historical conditions, certain specific constructions of masculinities become more effective than others in establishing and taking a share in male domination.

As for the concept of "masculinities", it has been underlining the fact that masculinity is not universal, but plural and diverse. Thereby it makes a parallel political emphasis with feminism by suggesting that it is possible for masculinities to (be) change(d).

Today the field of "critical studies on men and masculinities" is gradually making more room for itself in social sciences, becoming known by a larger number of people every day, and is constantly developing and thriving with new studies conducted in the world, including Turkey.

The research and studies of (pro)feminist and anti-sexist social scientists and activists on men and masculinities have always been met with skepticism by feminists and LGBTQIA+ studies both in Turkey and the world. Since patriarchal and (hetero)sexist relations are already being discussed by these fields of study, is there really a need for masculinity studies? In fact, the raison d'être of "masculinity studies" and "critical studies on men and masculinities" and what they do and/or can(not) do lies precisely in the answers that are given to this question.

Connell and her (Connell's chosen gender pronoun is she) friends, who were men originating from the same tradition with feminists and feeling uncomfortable with the impact of patriarchy on women and LGBTQIA+ individuals, initiated this field of study in the 1970s with extremely political motivations and not for the sole reason of scientific interests or because they found the subject matter interesting, unexplored or with the potential of becoming popular.

This motivation at its inception was to examine how men turn into patriarchal and (hetero)sexist actors and to reveal the conditions of their change. Due to the differences and priorities in their own agendas, feminism and LGBTQIA+ studies were criticizing patriarchy and (hetero)sexist relations by focusing on women and/or LGBTQIA+ individuals. Their focus was not directly on the criticism of men, who are in a dominant position in these relations, or of the ways in which these masculinities are constructed.

"Critical studies on men and masculinities" set out to have a say in this very field that was not explored in the criticism of gender relations but was, in fact, extremely necessary.

The field of "critical studies on men and masculinities" criticizes masculinities from the inside. In this context, it can be characterized as an extension, part and continuation of critical studies in social sciences. This field aims to engage in a critical analysis of men and masculinities by standing against oppressions, exploitation, discriminations as well as subordination of women and LGBTQIA+ individuals.

That the concepts of "hegemonic masculinity" and "masculinities" of Connell have been widely accepted does not stem from the fact that this field or subject has become popular. The significance of Connell stems from a political reason. This reason is the following: She has put forward a critical theory, which discusses the construction of masculinities by explaining the possibilities of change in masculinities themselves.

In the last forty-year period since the late 1970s, when the first studies were conducted, to date; the field of "critical studies on men and masculinities" has enabled the critical discussion of a series of subjects that never came to the fore before such as patriarchal "masculinity" codes, climacteric of men, young men, fatherhood and becoming a father, work-masculinity relations, daily lives of men, impact of patriarchal discourses on men's bodies, masculinities and sexuality, masculinities in nationalist discourses, sports-masculinity relations, representations of masculinities in literature, cinema and media, and constructions of masculinities in different local contexts.

Male researchers, who tended to engage in a harsh criticism of masculinities by following feminist discussions and self-criticizing their own lives, might have initiated the field of critical studies on men and masculinities.

However, today there are as many women researchers working in this field as men. Here, I would like to underline the importance of being critical on any account while doing research and writing on gender and leading our own lives.

Because (patriarchal and (hetero)sexist) men and masculinities are the perpetrators of oppression, violence, harassment, rape and discrimination, which women, LGBTQIA+ individuals and other men behaving differently than the dominant masculine identity have been subjected to; they are the ones who have been benefiting from the unequal and hierarchical gender relations; they are the ones who have been causing women to feel uneasy while going out; they are the ones who have been occupying the spheres of daily life as they wish ranging from economics to law, from interpersonal discussions to the adjacent seats on the subway; they are the actors who have been dominating the patriarchal relations...

In short, they are the ones who have been making public and private spaces unbearable for those who do not play "the game" according to the patriarchal and (hetero)sexist "rules". For that reason, the subject of "men" and "masculinities" is not just any "subject" that one can write about without pondering on and making a criticism of male-dominated power relations.

For instance, you cannot analyze men and masculinities as if you were analyzing a water glass, which could be attributed a neutral value (though I think a glass is also part of the network of political, economic and/or ecological relations) or you cannot approach men and masculinities as if it were any subject among (popular) subjects.

If you analyze them—like some do—as a popular subject independent of the network of relations among capitalism, patriarchy and (hetero)sexism, it would lose a considerable part of its significance and transformative power.

Or, while discussing men, if you write on the subject by overlooking the structural elements and social and historical conditions in its socio-cultural background and use an accusatory language towards the individual actors; or, while discussing masculinities, if you see masculinity as an indivisible whole and do not underline the possibilities of its change, the field would lose a considerable part of its critical potential.

It should also be noted that essentialist statements, which only contribute to the continuation of the existing state, are to be avoided while discussing men and masculinities and it should not be forgotten that masculinity is also a social construct.

What I would like to say is that in the field of critical studies on men and masculinities, qualified and exciting works are being done. To discuss men and masculinities, it is not necessary to have—though I wish there were—extensive, wide-scale theories or research where thousands or millions of people are represented. Men and masculinities are just beside us, they are realities that we come into contact with or are subjected to by us or the ones around us.

That is why, it is very meaningful that critical studies on men and masculinities attach a central importance to feminist self-criticism, which criticizes itself in the first place.

When this is not done, the field becomes meaningless.

(For instance, what good is it if a man, who commits violence or despises homosexuals, makes a criticism of masculinity? Or, the big question: "Why would men, who take the biggest share in patriarchy, criticize masculinity?")

It is of considerable importance to analyze men and masculinities from a critical perspective because male domination and (hetero)sexism have been turning the lives of everyone—including those of men—into hell. Maintaining this is not an attitude that life deserves. Masculinity studies is an opportunity for change emerging from the academia. But it is only when they are critical that these opportunities can be actualized.

***

Men should change so that patriarchy and (hetero)sexism can disappear. It is possible to change! (MB/ŞA/APA/SD/IG)

* Images: Kemal Gökhan Gürses

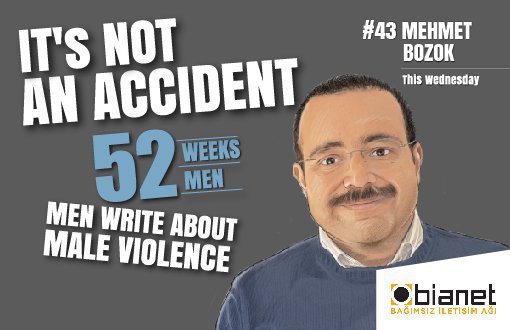

** A quotation from the song of Jimi Hendrix "Castles Made of Snow"