Photos: Nurcan Keskin

Click to read the article in Turkish

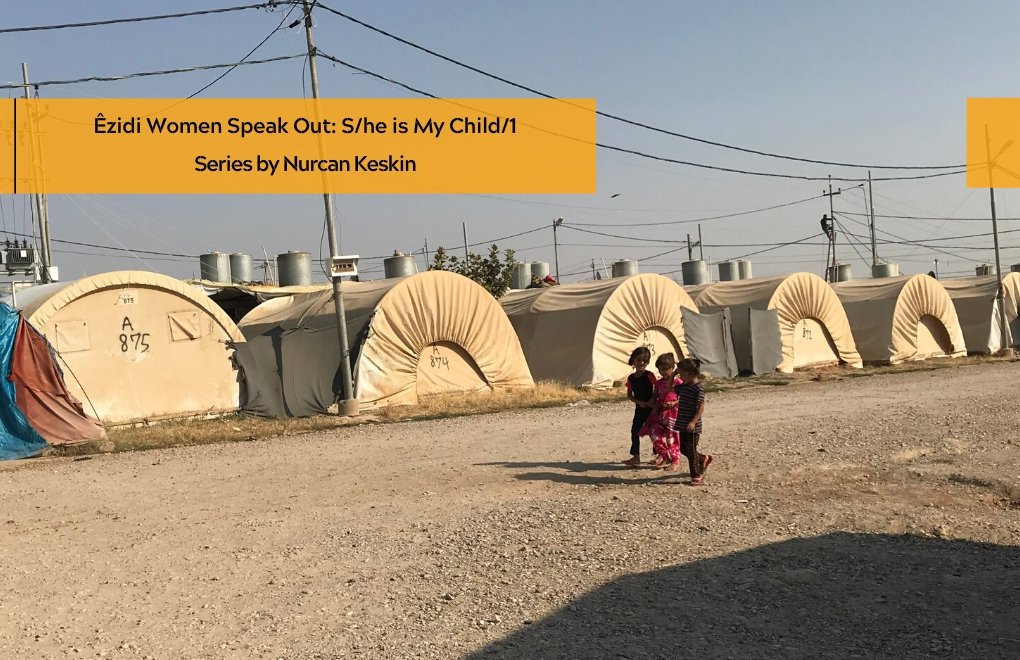

Zozan's mother greets me in a worried tone just outside the gate to Sexhan camp, near Duhok. She cautions me against telling anyone I am a journalist, telling me rather I should say I was a volunteer at a camp she had previously stayed in. She takes my arm, telling me we should leave right away.

This agitation on her part communicates itself to me as the taxi we have got into stops near the center of Duhok after which she hurriedly leads me through several side streets. The woman who opens the door to the house we stop at turns out to be Zozan's aunt.

We are greeted by Zozan in the hall, my anxiety lifts upon seeing the smile on her face and the laughter in her voice. I am not the only one to respond to Zozan's spirited presence. An old lady sleeping on a cot in the corner, who I learn is the mother of the aunt, also wakes up at her voice. Unlike me though, she is not pleased and grumbles as she tries to go back to sleep.

Mother and her daughter

As Zozan's mother takes off her purple turban in the back courtyard, I notice her striking resemblence to her daughter. Zozan cheerfully remarks, "Look at how young she looks!," but I am the only one to smile at this. There is a pattern to the responses of Zozan's mother and her aunt to her, a combination of irritation and asperity.

We have been seated for under 20 minutes, when disregarding her mother's verbal admonitions and her aunt's censorious looks, Zozan tells me she used to sing at weddings in her village and that some videos of her singing from all those years ago could even be found on Youtube. Her mother is irritated at this and keeps grunting her displeasure.

I ask them if I can speak to Zozan alone, but they tell me "We know everything, you can speak in front of us," and make no motion to leave. Her mother is angered when Zozan begins to speak of the child she is pregnant with and shushing her, begins to speak herself, silencing Zozan, narrating the details of what Zozan underwent when she was in captivity.

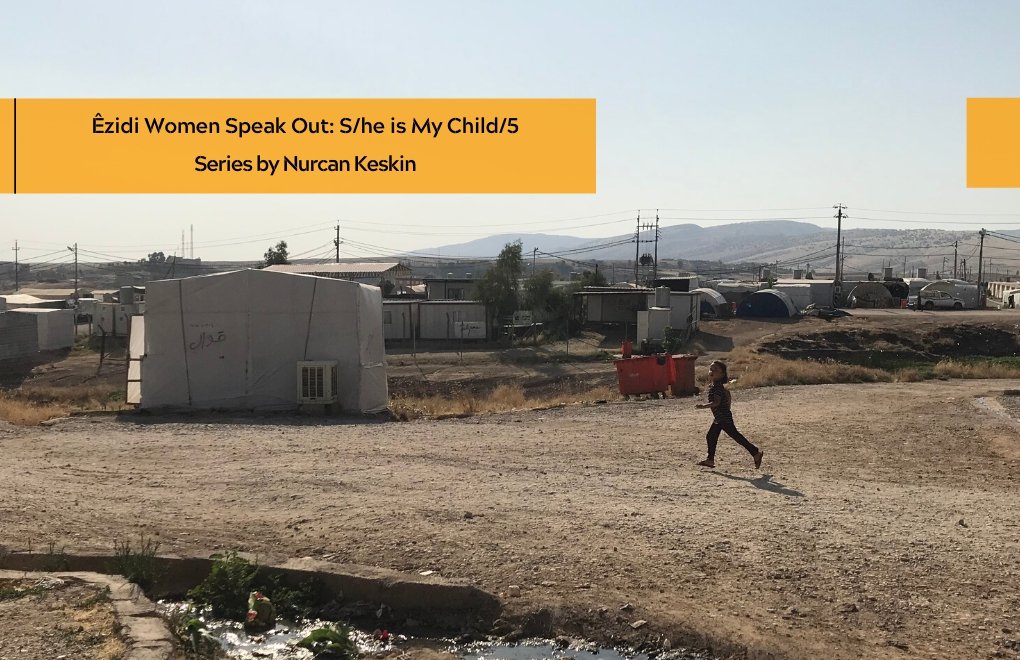

Zozan and her elder brother were taken captive by the ISIL when they attacked the Kocho village in August 2014. There has been no news of her elder brother ever since. Zozan herself was held captive for five years and it was only earlier this year, when ISIL lost territory to the Syrian Army, that she was able to regain freedom. Zozan's family were staying in a camp in Iraq and while they initially rejoiced at hearing from her, upon learning that she was pregant, refused to accept her back. It took Zozan two weeks of pleading, during which time she slept on the floor of a police station in Aleppo, to persuade her family to let her come back to them in Iraq.

With two conditions

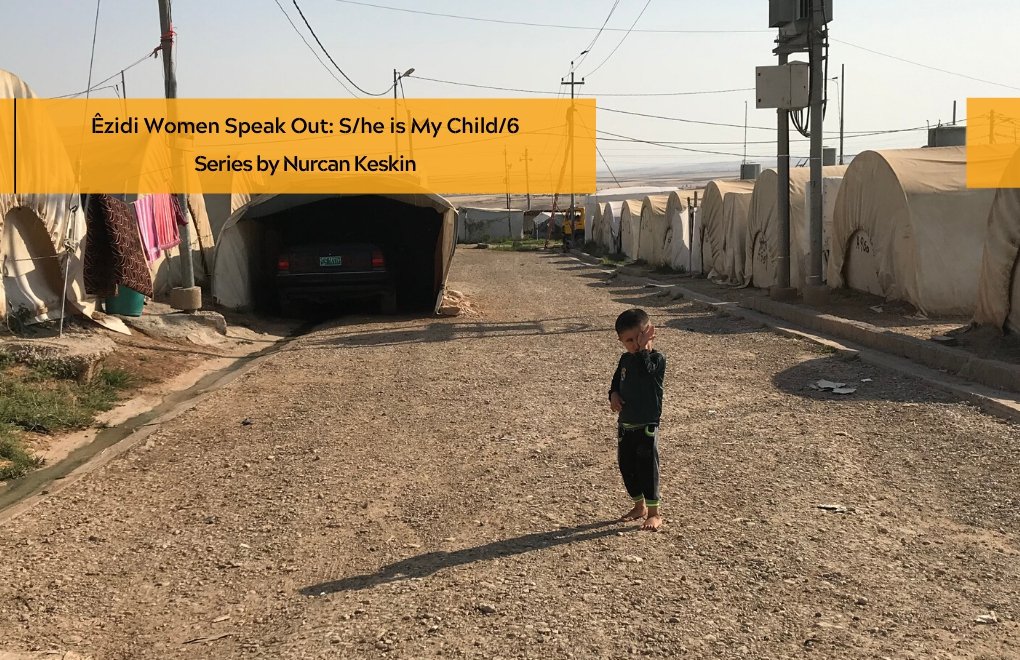

However, her family placed two conditions on her return: I met with Zozan not in the camp her family were staying in but in her aunt's house where her family insisted she stay in, out of sight of everybody, for the term of her pregnancy. Now six months pregnant, Zozan tells me, "Yours is the first new face I have seen in months." Her family's second condition was that Zozan give up her child for adoption immediately after its birth.

Zozan is resigned to her situation which is a house arrest in all but name. Even as she says, "All I wish is that this second child not be taken away from me too," her mother tries vigorously to turn the topic to what she had suffered during her captivity instead.

Only 14 when abducted, she never learnt the name of the place she was first taken to, but tells me she was held captive in a school. After being kept without food for days, she was taken to another school with several other young Ezidi girls. After a few months, when she was forced to learn how to pray by women ISIL members, she was sold, together with a fellow Ezidi girl, Meryem to an old man she had never seen.

She tells me she suspects the old man was Saudi, but did not know whether or not he was a fighter. He was however armed, had several female servants as well as several males guarding his property and had a high status where he lived. Around a year after Zozan and Meryem were bought by him, one night, the house was stormed by armed ISIL militants who executed the old man. Zozan tells me she suspects the cause was a factional fight within ISIL, but knows no further details.

The ISIL militants then took Meryem and Zozan away to a high building that she would learn later was one of the major ISIL police stations in Rakka. She narrates how the basement of the building which was used for many different purposes, had cells where many young Ezidi women were kept. At frequent intervals, ISIL members would come and rape the women there, often violently. Beatings were common. She moves to show me her scars, but changes her mind.

Five days

After seven months in the station, she was taken away in a truck together with several other young women to a different center, where those in charge were high ranking women ISIL members. Many women gave birth here. The days were filled with verbal and physical abuse towards them by the ISIL women that she remembers living in a trance.

On a cold day in December, whose date she does not remember, she gave birth to a girl child. "I only saw her for five days," she tells me, rubbing her stomach, "I do not want this one to be taken away from me as well." |

Zozan doesn't know who the father was and tells me her first child was taken away from her by the women ISIL militants and she never heard about the child again. Two weeks after the child was taken away from her, a Moroccan woman came to the center and bought her to serve her and her husband.

Zozan tells me of how she was constantly abused by the couple, beaten and humiliated and how the woman would constantly fill her ears with the group's propoganda, speaking in a rapid and incomprehensible Arabic. ISIL women militants would constantly visit the house and often mock Zozan, touching her like she were a piece of wood.

Despite her mother's directions, Zozan constantly turns the topic to the child she is pregnant with and it only on these occasions that she smiles, a radiant smile that warms the heart.

She thinks that the Moroccan man who raped her and left her with child, is probably in a prison under the control of the Syrian government, together with his wife. Under no circumstances will she let this child be taken by them. And despite her family's insistence, she does not want to give up the child for adoption, but she is resigned to not having a say in this matter.

Roj, the word for Sun

She doesn't know its' gender but tells me she wants to name the child 'Roj' if it is a girl. "Before my first child was taken away from me, I whispered 'Roj' into its' ear", Roj, the Kurdish word for 'Sun'.

When I ask her what she would call it if it turns out to be a boy, she is nonplussed. Smoothing out her jet black hair she has been rolling her finger around in for hours, she says laughing, "I don't know, I never thought of it."

“She goes on, "During my first pregnancy as well, I knew it would be a girl. The ISIL women told me they would name the child 'Hatice' but I whispered the name 'Roj' in her ear before they took her away from me."

Her mother has been becoming more and agitated at hearing Zozan speak of her child and makes to quiet her, but she ignores her, saying "I wish this child never be born, that it always stay here with me, here in my womb."

The Spiritual Council

The decision by the Ezidi Supreme Spiritual Council (the Ruhani council) to not accept "Children born of ISIL militants" is not the only reason she is being forced to give up her child for adoption. Her father and two elder brothers are insistent on her giving up this child to an orphanage as well.

Her brothers have not visited her once during these two months she has been at her aunt's house.

Zozan tells me she understands the decision by the Ruhani Council as well as her brothers' insistence, but says, "I do not believe this is right. That I should abandon this blameless child."

Forgetting

"Yes, I will remember, every time I look into her face, but what if I abandon her? Will abandoning her let me forget?"

During the four hours we spent speaking, Zozan's mother frequently insists that they would not keep the child. She shows no understanding for Zozan's desire to not be separated from her child.

When I move to tell her of the psychological counseling and other services available at international aid organizations and the UNHCR, she waves me away, "I know them all and they all know about us and situation as well."

As we part, Zozan embraces me and stays in the living room as her aunt walks with her sister and myself to the door, where we head our separate ways, Zozan's mother towards the camp, myself towards Erbil. (NK/SD)

Tomorrow: Meyrem: We are left with no choice but to leave for afar

Ezidi Women Speak Out: 'S/he is My Child'

Meyrem: We are Left With No Choice But to Leave for Afar

Two Sisters, Fahima and Rayan and Their Cousin Seher

Leyla: The Only Thing That Keeps me Going is the Hope to See My Son Again

The Mosul Dar Al-Zahur Orphanage

'Êzidî Women are Breaking the Mould and Remaking Their Society'