Click to read the article in Turkish

"She began private tutoring during her second year in high school. With the money she earned she bought herself a pair of green cords, from the Grand Bazaar I think, while shopping with our mum, and she was extremely pleased. They really suited her. She was wearing those cords on 1 May. And the red jacket she had on belonged to Filiz." Hale Yeşilnil, sister

"This year finally, at the last minute, her older sister told me where Jale was buried. After 43 years I was able to commemorate Jale beside her grave. Mücahit and I removed the weeds from her grave and planted purple, red, and green flowers. Her sister said Jale liked daisies, so we didn't forget the daisies." Kadir Akın, friend

Jale Yeşilnil is perhaps one of the most well-known of those who lost their lives on 1 May 1977.We recognise her from photographs held up each year at the First of May commemorations, and especially those held by women.

Jale was just 17 years old when her life was taken from her on 1 May 1977. She was always sensitive towards others and what was going on around her. She wanted to become a doctor and examine and treat the poor for free.

On 1 May 1977 she left home for a picnic with her friends in Çamlıca. Her mother helped her prepare. But Jale never returned home again.

According to the autopsy report, the cause of her death was mechanical asphyxia accompanied by rib fractures as a result of compression of the chest and abdomen.

Her older sister, Hale Yeşilnil, had not spoken to anyone about Jale until today. She named her daughter after the sister she had lost.

We hear Jale Yeşilnil's story from Hale Yeşilnil, who speaks of her younger sister with great love, compassion and admiration, and from the author Kadir Akın, who knew her from the Göztepe Cultural Association.

Hale Yeşilnil, sister

My father was a railway station manager at the Turkish State Railways. We moved to the Gölbaşı district of Adıyaman when he was transferred there. That was the year I started primary school, and on 15 June 1960, my sister Jale was born there.

It was a beautiful June morning. My mother delivered all of her children at home with the help of a midwife. Before Jale's birth, my older brother and I were sent out into the garden. My mother's Kurdish helper, our bacı, informed us when the birth was over.

When I arrived at my mother's side, I saw a baby with wide open eyes, and a beautiful smile that I remember to this day. She was beautiful. I can honestly say that I never heard Jale cry. Sometimes my mother would wake her up because she had been sleeping too long.

Even at this she would smile as she opened her eyes. Jale had a childhood filled with love and joy. I witnessed several occasions at different gatherings when people would turn to look again at her ever-smiling face.

When my father was transferred to Nazilli, my mother's Kurdish helper who we all loved dearly, wouldn't leave the station until the train had left. "How will I live separated from this beautiful girl of mine," she wept. Yet she herself was a mother of six, back home in her village which was an hour and a half, maybe two hours away.

We had educated, enlightened, democratic parents. We were all fortunate in this very fundamental way. My father was, by disposition, a man of few words, but my mother was very different. Jale inherited my mother's beauty and temperament. She was naturally productive, creative, and strong. She read a lot.

When Jale was two years old, we left Gölbaşı and moved to Nazilli. We stayed there for two years. Jale was five when my father was transferred again, to Istanbul this time. They had chosen to return to Istanbul because of my ongoing treatment.

My fourth sibling was born in Nazilli. Unlike Jale, this baby cried so loudly, and at all hours of the day, that it often drove us out of the house.

Jale would stand beside the cradle and, although still a little girl herself, she would hush the baby affectionately.

When we first moved to Istanbul, we lived in Zuhuratbaba, in the Bakırköy district, for four years. We had a landlord, Uncle Kirkor, who we all adored. They were a little reluctant at first to rent the house to a family with four children. Then he set eyes on five-year-old Jale holding my father's hand. Uncle Kirkor always said he had never seen such a sweet child.

I had to undergo serious orthopaedic surgery at Çapa Hospital. I wasn't supposed to put on any weight on my foot for months. Jale would play games with our younger sibling and include me by offering me treats.

They were great at playing house together. Jale was loving towards everyone and she was very generous too.

One day Jale told my mum that she didn't want to go to school, that she wanted to be a bride. Peruz Abla was getting married and was going to move into the flat upstairs. My younger sibling and I stayed at home, while my mother took Jale with her to the wedding ceremony.

"I'm going to be a bride just like that!" Jale had told my mother as they left the ceremony. My clever mother responded, "But darling, when you go to school, among the many things you'll learn is how to sign a document. And didn't you see just now, that in order to be a bride, you have to be able to sign papers." After that Jale kept asking when she would start school.

The year we moved to Göztepe we were happy to be moving into our own home, rather than the lodgings provided by the state whenever my dad was transferred. Jale started Yeşilbahar Primary School. She was a very bright student. She was just as successful later at Göztepe Middle School, completing her classes every year with merit.

She graduated first in her class from Göztepe Middle School. Along with her certificate, she was given a necklace with a gold "J" pendant. I was the only one at her graduation ceremony. My mother was with my father at the Cerrahpaşa Faculty of Medicine, where he was hospitalised. At the end of the summer, in September, my father passed away, just after turning fifty. I remember Jale's tear-filled eyes at the time of this painful loss.

My older brother was a fourth-year student at Istanbul Technical University's Faculty of Electricity, I was a second-year student in Chemistry at the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture. My 46-year-old mother had to survive on my father's pension while taking care of four children. They were difficult times.

My mother was a housewife. But back then she would also do sewing and embroidery work to better provide for us. Jale registered at Aryamehr High School (now 50. Yıl Tahran High School) which had newly been founded with the support of Rıza Pehlevi. She was a successful student in first and second grade. She received a certificate of honours every term.

She grew into a joyful, energetic young woman, she was fond of fashion and cared about her appearance, she liked make-up and everything just seemed to suit her. She used to love Nükhet Duru. She sang her songs so beautifully.

Every year of her life, she would prepare a different skit each Father's Day and Mother's Day. She would take the stage with our younger sister. But she always played the lead. She would prepare the lemonade herself and serve it with biscuits she'd bought with her own pocket money.

She was productive, talented, generous and full of heartfelt love, just like our mother. And she'd always offer a bunch of daisies that she'd picked from the side of the railway tracks that passed by Erko Sitesi, the housing complex where we lived.

Sometimes on weekends in the summer, the whole family would go to the beach of our father's [State Railways] Camp in Fenerbahçe. And sometimes on weekdays, the two of us would spend the whole day there, eating sandwiches that my mother had made. We'd get in free because we had a card. And we could get there and back on foot.

She met Orhan Özay at camp and they became close. Back then we lived at number 30, Çam Apartment Building in Erko Sitesi. I know Filiz from B-block, I think they were friends since primary school. Our mothers knew each other from neighbourhood home gatherings.

Sometimes she would borrow clothes from Filiz and wear all different sorts of things. She loved dressing up. She began private tutoring during her second year in high school. With the money she earned she bought herself a pair of green cords, from the Grand Bazaar I think, while shopping with our mum, and she was extremely pleased. They really suited her. She was wearing those cords on 1 May. And the red jacket she had on belonged to Filiz.

When we were little, Jale and I both wanted to be doctors. We were all delighted that Jale wanted to be a doctor. In the years that followed she developed her plans further. She was going to work in Anatolia and treat patients for free at least two days a week, and she would never charge those who couldn't afford it.

We have two witnesses for the First of May. My older brother and Orhan Özay. Orhan was the one who came to our home to let us know. He said that she'd been hurt, and he and my brother left together. Then my brother identified her at the morgue.

My mother and I weren't allowed inside Osmanağa Mosque. My brother never ever spoke about this. Our relationship has never been that great anyway because of our different political views.

In the days that followed, when I asked Orhan, he never confirmed what happened with the tank. He just mentioned the wounds she had sustained from being dragged along. Orhan was first a militant of the Liberation [Kurtuluş] movement, and then later he became a militant with the Marxist-Leninist Armed Propaganda Unit [MLSPB]. He was severely tortured during the time of the Military Coup of 12 September [1980]. He was sentenced to execution. Unable to stand the severe torture, and partly due to pressure from his mother, he confessed and became an informant.

And then one day he was shot and killed by the police. And so, unfortunately, I really can't say exactly what happened [to my sister], no one knows. But aunt Şule, the daughter of my mother's uncle, who was there to wash Jale, only mentioned the wounds. In 1980, I did everything I could to get the morgue report, but it was no use.

After Jale's death, people we didn't know got in touch to express their condolences.

Our relationship with my brother, which was not great anyway and could become quite hurtful at times, got worse after my dad died. My brother doted on my two sisters, but his love for Jale was special. He was full of hopes and was a real believer. When 1 May 1977 happened, he was a reserve officer in the Naval Forces. All leaves had been cancelled but upon my mother's request, he was able to get leave and come to Göztepe.

All during the final week leading up to the First of May, my mother and I argued constantly. Even three days before 1 May, I wasn't allowed out. She was always worried because I couldn't run. "If you go, I'll tie myself to the railway tracks!" she yelled at me once. I remember saying "How could you? You're a warm and loving mother to all your children!"

But on 1 May 1976, she herself had woken me at 5.30am, only reminding me to be very careful. My mother was a well-read, informed, educated woman. She knew very well that there would be provocations and that trouble would break out.

"I both knew and didn't know that Jale would be there that day."

I have always wondered why it had to be Jale and not me. She should have lived. This only added to my sorrow and I've had to live with this feeling for years.

I'll never forget two conversations the two of us had. She had a literature teacher in high school, Mehmet Başaran. A superb author and wonderful person, my mum and I had read and loved his books. After 1 May, he, his sibling and teacher friends often provided us with support.

One day, Mehmet Başaran assigned Jale the task of interviewing Aziz Nesin. She showed me the notes she had taken before the interview, questions she was going to ask him. She asked him about Anatolia's one hundred years of solitude, why the people were left in ignorance, the reasons for the poverty of these ignorant but beautiful people, and the cause of the deprivation they faced and the lack of equal opportunities forced upon them.

Among her notes, alongside the autobiographical account of what the great author Aziz Nesin had and had not been able to achieve, and his goals and projects, were Jale's own thoughts and suggestions. She asked me afterwards, "How did you find it, sister? I want to hear what you think." I thought for a moment but I had nothing more to add. "Jale," I said, "I think it's perfect. But you know I'm not really in a position to add anything."

The second conversation I'll never forget took place the week before 1 May 1977, on the Thursday. I was at home. I was standing in the kitchen and it was just the two of us at home. Because my brother was a reserve officer, he only came home on the weekends. My mother and my youngest sister weren't home either.

"Shall we have a talk, sister, the two of us?" she asked. She placed an orange and an apple on a plate, and we went into the living room. I was on the couch, and Jale was sitting in an armchair. "You and our brother have a strained relationship, and I haven't been that close to you either, sister," she began. I objected. "Our brother just wants to protect you all, because he loves you so much. And I love you and my brother so much too," I told her, "but it just doesn't seem to work. He always sees me with my head stuck in the clouds, I know he loves me too but that's just how he is, he won't change." And she said, "He's going to be here at the weekend, mum's not going to let you go to the First of May rally anyway," she said. Then she asked my opinion about the First of May and the Liberation Movement. The Göztepe Cultural Association that Jale went to was aligned with the Liberation Movement. I knew her friends Murat and Hüseyin. We talked about them.

"You know mum's right when she says there'll be provocations, Jale," I told her, but I still didn't understand why mum would forbid us from going. "I'm going with an organisation, our friends are strong and they always look out for their crowd, we saw the same thing at the Cerrahpaşa incidents. What do you think?" I asked her.

"I'm going to Çamlıca with friends from school, on a picnic, but of course I wish I could go to the First of May," she said. I didn't bother repeating that something was definitely going to happen, and that it was better to go to the rally along with an organisation.

When Jale woke up on Sunday morning, 1 May 1977, I was awake in the living room lying in my sofa bed. Mum was already awake too. I could hear them talking in the kitchen. Jale was boiling eggs while mum helped her get ready. I both knew and didn't know that Jale was going to be there that day. Why didn't I insist and make sure I learned for certain? This is something that still pains my heart.

As soon as I got out of bed, I said to my mum, without even saying good morning, "In 1976, just about the same time you saw Jale off this morning, you said goodbye and sent me off to the First of May with a smile on your face. Now, by giving Jale your permission you've really hurt me," I continued. "She's gone on a picnic with her friends, while I have to stay at home!" Mum replied, "I pray for everything to turn out okay, but violence is expected to break out. I'm praying that won't be the case, that only good comes of it. But that's why I couldn't let you go this year, please understand me, my dear."

The nightmare began with the news on television that evening. No one dared speak. We grew more and more worried as the hours passed and Jale still hadn't returned. My mum and I hugged each other every now and then, crying.

It was almost 10pm when her close friend Orhan arrived. As my brother was getting dressed to leave the house, I hugged Orhan and asked, "Is she really just wounded? She is alive, isn't she? What we saw on TV was terrible." Orhan hid the truth. He said she was wounded. He and my brother left. My brother didn't return, so at around 1am we went to Zeki Coşkun's house, he lived quite close. His mother said he wasn't at home. But he was.

It turned out that as they were walking down Kazancı Slope, Jale had gone back to the square.

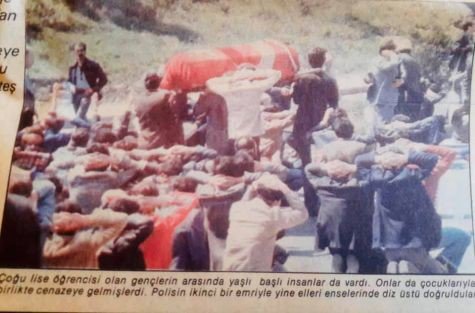

Jale's body waited at the morgue from 1 May to 5 May. Meanwhile, police officers, some plain-clothed and some in uniform, kept visiting our house. I just sat in the kitchen waiting for the front door at the end of the hall to fling open. Her friends from school kept begging us, saying, "We're not going to leave her body unclaimed, are we?" We all became so close at that time.

On the morning of 1 May my brother came home devastated. Then a doctor showed up and gave us all a shot of Diazepem. We were all out of sorts under the effect of the drug. The next day, when the doctor came back and our family friends told him I hadn't slept, my mother, brother, and younger sister, we were all given shots again.

On the second day police officers started showing up. They told us that the body had to be buried as soon as it was picked up from the morgue. The plain-clothed police officers had found out from the undercover police at Istanbul Technical University [İTÜ] that I was a member of the Istanbul Technical University Faculty Association [İTÜ-DER]. I promised them that, apart from five or six of her other friends, the funeral would mainly be held with her friends from class and school, a group mostly aged 16-17, but I told them that we would march.

Jale was being carried on shoulders when I said that she would be buried next to my father in Karacaahmet. My family was hesitant, and rightly so. We were finally given permission to march beyond Osmanağa. The Police Association [Pol-Der] gave us a lot of support at the time. The fascist coup of 12 September was what finished them.

Outside of Osmanağa Mosque, we began our march. Her friends from school didn't even let my uncle carry her coffin. "Please uncle," they told him, and made their way.

Just as the cortege had taken its position under the bridge, we were stopped by police officers with Kalashnikovs. They yelled for everyone to put their hands up and lay down. And that's when I got scared. Not for myself, but for the group that was mainly made up of 16-17 year olds.

Some were there with their mothers and fathers. But they hadn't wanted to leave their friend Jale to anyone, and they didn't leave her to the police officers carrying Kalashnikovs either. They were not afraid, not one bit. They stood there with their hearts of gold, and they never let Jale fall to the ground.

They took turns carrying the coffin as they let the police search them one at a time. When I lifted my head up to see them, I got kicked. My uncle was next to me and he got hurt worse. But there was no panic or chaos among the group.

The march went on and we managed to reach the Karacaahmet Cemetery with Jale on the shoulders of her friends. Then we buried her. My dear sister in the spring of her life, who was as wise as a grown person.

Jale, you and Yusuf Aslan, Hüseyin İnan, Deniz Gezmiş, Mahir Çayan, and so many other revolutionaries set fire to my heart, and what a fire.

Let light be with you, my dear sister. The stars will always be your comrades.

You will not be forgotten.

So long as the sun rises and the sun sets, you shall all live.

Kadir Akın speaks about Jale YeşilnilWe were just becoming organised on the Anatolian side. I used to live in Üsküdar/Çiçekçi, and in addition to the association in Çiçekçi, I regularly visited the Göztepe Cultural Association [GKD] too. I was 19 years old. A couple of times we had meetings with friends there and Jale was with a group of seven or eight students from the Aryamehr High School. We also came across each other at a few activities on the Anatolian side. On 1 May 1977, the Liberation group, the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey [DİSK], and the Mineworkers' Union [Maden-İş] had all gathered in Saraçhane, so the Revolutionary High Schoolers [Dev-Lis] were there too. I didn't see Jale in the crowd that day. By evening on 1 May, news of those dead was starting to come through. We found out that Jale was dead the next day in the afternoon, and of course we were devastated. To find out that we had lost a friend who had marched in the same contingent with us on 1 May was unbearably sad. And of course, it wasn't just Jale, dozens of people we never knew died there that day too. Every loss was met with extreme sorrow. The next day everyone was in shock, no one could have guessed we would lose so many people that day. After receiving the news, our final duty was to bid her farewell in a ceremony. We contacted her family. We were able to hold the ceremony on 5 May. We gathered outside the Kadıköy Osmanağa Mosque and formed a cortege. We were taking Jale to the family grave in Karacaahmet. A great number of people attended the funeral that day. There were people who had come from Çiçekçi and Göztepe. The Tepe Nautilus shopping centre that stands there now hadn't been built yet. But the road to Karacaahmet had been, it was a new road. We started walking down that road, carrying Jale on our shoulders. We were under an overpass and had nearly reached Duvardibi when I saw police cars close in on us and tens of plain-clothed police officers surround the whole cortege. I was at the very front so I could see everything. They told everyone to lie down. Those carrying the coffin objected and told them that they were not putting the coffin down. A few carried on holding Jale. We later found out why this had happened. There had been a skirmish during a raid on a socialist association in Kadıköy, and a couple of officers had been wounded. They stopped and searched us because they had received information that those involved in that skirmish might have infiltrated the cortege. They were extremely rough, they made people lie face down on the ground, and beat them, but no one was taken into custody. We continued the march again, shouting slogans. Then we sent Jale off on her final journey. Jale was a very beautiful young woman. Anyone who saw her, even only once or twice, was unlikely to forget her face. This year finally, at the last minute, her older sister told me where Jale was buried. After 43 years I was able to commemorate Jale beside her grave. Mücahit and I removed the weeds from her grave and planted purple, red, and green flowers. Her sister said Jale liked daisies, so we didn't forget the daisies. Commemorating Jale beside her grave exactly 43 years later, has taken us right back to those days... |

(TY/APA/EKN/VK)

About Tuğçe YılmazJournalist, editor, researcher. "1 May 1977 The Voices of Those Who Lost Their Loved Ones / 1 May 1977 and Impunity" she was engaged in this dossier as a researcher, reporter, editor and writer. Her articles, interviews and reports are published in outlets such as bianet, BirGün Book, K24, 5Harfliler, Gazete Karınca and 1+1 Forum. She graduated from Ege University, Faculty of Literature Department of Philosophy. She was born in Ankara in 1991. |

|

| This text was created and maintained with the financial support of the European Union provided under Etkiniz EU Programme. Its contents are the sole responsibility of "IPS Communication Foundation" and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. |

CLICK - 1 May 1977 e-book is online

The ones who lost their lives on 1 May '77The ones whose loved ones we could talk to: Ahmet Gözükara (34, teacher), Ali Sidal (18, worker), Bayram Çıtak (37, teacher), Bayram Eyi (50, construction worker), Diran Nigiz (34, worker), Ercüment Gürkut (27, university student), Hacer İpek Saman (24, university student), Hamdi Toka (35, Seyyar Satıcı), Hasan Yıldırım (31, Uzel worker), Hikmet Özkürkçü (39, teacher), Hüseyin Kırkın (26, worker), Jale Yeşilnil (17, high school student), Kadir Balcı (35, salesperson), Kıymet Kocamış (Kadriye Duman, 25, hemşire), Kahraman Alsancak (29, Uzel worker), Kenan Çatak (30, teacher), Mahmut Atilla Özbelen (26, worker-university student), Mustafa Elmas (33, teacher), Mehmet Ali Genç (60, guard), Mürtezim Oltulu (42, worker), Nazan Ünaldı (19, university student), Nazmi Arı (26, police officer), Niyazi Darı (24, worker-university student), Ömer Narman (31, teacher), Rasim Elmas (41, cinema laborer), Sibel Açıkalın (18, university student), Ziya Baki (29, Uzel worker), The ones whose loved ones we did/could not talk to: Aleksandros Konteas (57, worker), Bayram Sürücü (worker), Garabet Akyan (54, worker), Hatice Altun (21), Leyla Altıparmak (19, hemşire), Meral Cebren Özkol (43, nurse), Mustafa Ertan (student), Ramazan Sarı (11, primary school student) The ones only the names of whom are known: Ali Yeşilgül, Mehmet Ali Kol, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı The one whose name is unknown: A 35-year-old man |

The voices of those who lost their loved ones: 1 May '77 and impunity

Political panorama of Turkey-1977

Film industry worker Rasim Elmas, 41, died in Taksim

Construction Worker Bayram Eyi, 50, died in Taksim

Teacher Bayram Çıtak, 37, died in Taksim

High School Student Jale Yeşilnil, 17, died in Taksim

Teacher Kenan Çatak, 31, died in Taksim

Teacher Ahmet Gözükara, 33, died in Taksim

Teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü, 39, died in Taksim

Student-laborer Niyazi Darı, 24, died in Taksim

University student Nazan Ünaldı, 19, died in Taksim

Teacher Ömer Narman, 31, died in Taksim

Laborer Ali Sidal, 18, died in Taksim

Counterperson Kadir Balcı, 35, died in Taksim

Student Hacer İpek Saman, 24, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Kahraman Alsancak, 29, died in Taksim

Laborer Hüseyin Kırkın, 23, died in Taksim

Student Ercüment Gürkut, 26, died in Taksim

Public order police officer Nazmi Arı, 26, died in Taksim

Laborer Mahmut Atilla Özbelen, 26, died in Taksim

Factory worker Hasan Yıldırım, 31, died in Taksim

Itinerant salesperson Hamdi Toka, 35, died in Taksim

Security Guard Mehmet Ali Genç, 60, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Ziya Baki, 30, Died in Taksim

Laborer Mürtezim Oltulu, 42, Died in Taksim

Teacher Mustafa Elmas, 33, Died in Taksim

Student Sibel Açıkalın, 18, died in Taksim

Laborer Diran Nigiz, 34, died in Taksim

1 May 1977 & Impunity

'The state is implicated in this crime, perpetrators must be put on trial'

'If you can't find the killers, you can't remove the stain'

'The perpetrators of the 1 May 1977 massacre got away with it'

Remembrance as a matter of dignity and the fight against impunity

Who is hiding the truth and why?

.jpg)