Click to read the article in Turkish

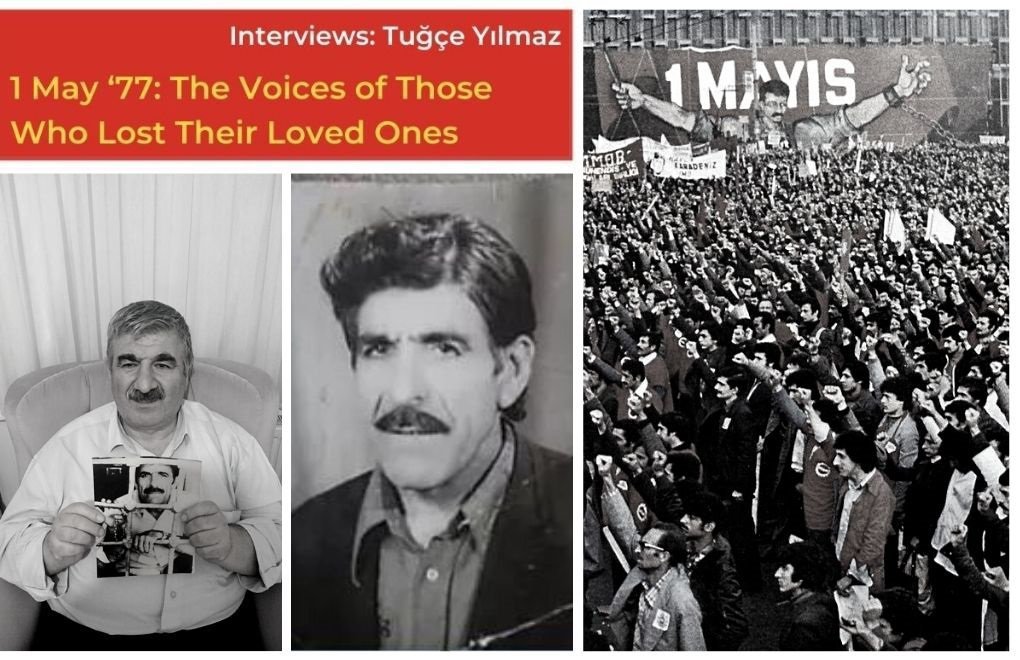

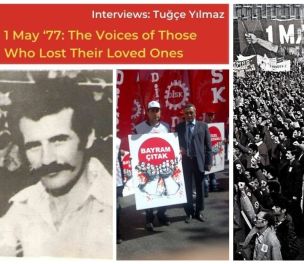

Construction worker Bayram Eyi was in Taksim Square on 1 May 1977. He died when a volley of gunfire was opened on the crowd. He was 50 years old at the time. He had come to Istanbul from the village of Soğuk, now known as Özler, in Erzurum-Aşkale, in the 1950s, marrying Resmigül towards the end of the decade.

Zeki Eyi, unbeknownst to his father, was also at Taksim Square on 1 May 1977. He was sharing in the elation of 1 May together with people he referred to as his "abiler ve ablalar"—his "big brothers and big sisters." He was 17 years old when his father died.

According to the autopsy report, the cause of death was mechanical asphyxia caused by compression of the chest and abdomen.

43 years have passed since 1 May 1977. Although there are plenty of videos about "The Bloody First of May" circulating even on social media, we have known little to nothing about the individuals who lost their lives that day. Zeki Eyi and his wife Naciye Eyi, together with their daughters Ayçe İdil and Ayşe Gülen, all welcomed us into their home to tell us this story.

Zeki Eyi told us about his father, about the First of May demonstrations of 1977, which he and his father both went to, unbeknownst to one another, and about the challenges and difficulties his father faced as a labourer.

Actually, it's difficult for me to talk about my father even now, I mean, it's hard. I get emotional.

A father leaves home one morning, but doesn't return that evening. That's a really hard situation for a child to deal with.

I was in high school when I lost my father. I happened to go to Taksim that First of May too, but I kept it from my father. I didn't tell him of course because I thought if he knew, he wouldn't let me go.

I mean, I knew there would be revolutionaries there, but what I saw that day was such a huge crowd of revolutionaries from all these different fractions. All of them were like big brothers and big sisters to me.

My dad didn't possess much in the way of theoretical knowledge, but he always spoke of his respect for revolutionaries. He talked about Deniz Gezmiş a lot, for example. My dad loved revolutionaries, he was proud of them.

One of the most important things I inherited from my dad was a respect for revolutionaries. So for example, I now view all of the revolutionaries of our generation, regardless of what fraction they belonged to, as my father's children. And the new generation, for me, are like my father's grandchildren.

I'm still not sure just how he ended up joining the First of May rally that day, but thinking about it over the years, this is what I figure must have happened: My dad had most certainly become acquainted with some revolutionaries. Maybe he got a pamphlet from them, or a newspaper, or maybe a magazine. So there must have been some people there that day that he knew. Of course, at the same time, he was an Alevi and a worker; that alone was sufficient reason for him to take part in the rally.

He must have got ready the night before, but he never mentioned to us that he was going to Taksim, so as not to encourage us, I think. After all, families behave protectively toward their children.

My dad was a supporter of the People's Republican Party [CHP]. Earlier we'd gone to Ecevit's demonstrations and the like, but, politically, 1 May 1977 was the most important demonstration my dad ever went to, I mean, as far as I know. And it was the first demonstration I ever attended.

If I'd told my dad at the time that I wanted to go to the First of May rally, he wouldn't have told me not to, but I didn't say anything, because I thought he'd try to stop me. And so I didn't tell him about it the evening before either. As a result, both of us actually ended up sleeping that night, I imagine, full of excitement about the demonstration the following day.

My dad was a construction worker. He was a wiper. They called them wipers, they wiped the tiles clean. He had his own machine. He didn't belong to any union, he worked on his own, with his own machine. Whenever there was a job, he'd take it. Most of the time though, he never got paid.

He called the rich "bigwigs." My dad talked with us a lot, shared his woes. In his words, he worked with bigwigs. He had a notebook where he wrote down the wages he was due that he never received. Or rather, a notebook where I wrote them down for him, since he didn't know how to read or write himself.

Someone told me they'd seen my father, that the contractors hadn't paid him again. My dad had a small fruit knife that he used to peel fruit for us. He'd brandished that knife, but just then a friend of his showed up. I'll never forget that. Whenever someone isn't given what they deserve, I think of my father doing that, of those contractors who didn't give my dad his due.

My dad had no tolerance for injustice. I have this one particular memory of him, for example. They'd come to destroy our shanty at one point, right while he was building it. My dad was sentenced to three months for resisting them, and he spent two months in prison.

The reason for it was that they wanted him to pay a bribe, to keep them from tearing the house down, but my dad refused. Besides, he didn't have the money to give them anyway.

Back then there was what was called the "Social Police," an earlier version of today's riot police. He got sentenced for resisting them.

I was nine years old. A relative of ours went to pick my dad up. He brought a package of raisins and roasted chickpeas that night. I was asleep when he arrived. When I woke up, I was so happy to see him. And ever since, whenever I eat raisins and roasted chickpeas, I think of him.

In my second year of middle school I got lung fever, came down with pneumonia I mean. My dad came and got me from school to take me to the tuberculosis dispensary. At that age, you don't want your parents showing up at school of course, but there he was, my father, and moreover he was crying because I was sick. And so there I was trying to calm him, saying, "Don't cry, dad." We went to the tuberculosis dispensary. There were two elderly doctors there.

When we went in for my exam, they lifted up my shirt. My brother had drawn the sign of Zagor on my chest in watercolour, because I was sick. When the doctor lifted up my shirt he laughed and asked me, "What's this now, son?"

I remember that they treated us really well. They were progressive, revolutionary doctors, I think. Or we just thought at the time that anyone who treated us well must be a revolutionary. Once we were back out in the hallway, they told my dad that I'd recovered. One of the doctors placed his hand on my dad's shoulder and told him, "Don't worry yourself anymore now, you anxious daddy."

Back then we didn't have a TV, we only had a radio. What I remember of that period is what my dad listened to on the radio, and things I observed in daily life. All the while, I was actually observing my father, I've finally come to realize that.

He'd go to the market, for example, and he'd immediately be pulling something out of a bag to give to the kids there. Once I did the same thing, imitating him, I gave a piece of candy, or something, to a kid, I don't recall exactly. My dad jumped in and told me, "If you're going to give a child something, you can't give them just one, you have to give them all of it." Human values were incredibly important to him. And he had this spirit of resistance that he got from being an Alevi.

After our house was torn down, they gave my father another punishment. This time he was given a fine of 500 lira.

The police were always coming by our place, being rude to us, saying things like, "Where's your father? Just tell him to go give his deposition already," or "Tell your father to get down to the station and give his deposition and be done with it." When I told my dad about it, he set off for the station of course. They threw him straight into jail, because of the fine. Our relatives put the money together and got him released. Once again, I was asleep when he got home, and he woke me up, he was smiling and he said to me: "Look at what happened now, son—you sent me to the station and they locked me up." I'll never forget the smile on his face. Anyone else would've been angry.

As for the kind of father he was, well, he was a great father. You know that saying, "A true father beats you and he loves you too." Well, my dad never treated us like that.

But once there was this thing that happened. I was in the first grade, and one day I told him, "I'm not going to school." He pleaded with me for an hour, telling me, "Go to school son, please. What else are you going to do if not go to school?" But by the end of that hour, he'd run out of patience, and rightfully so. There were these small shovels next to the furnace, he took one of them and gave me a good beating, making sure not to hit me where he could break something though. Then he set me down on his lap and said, "Let's see you not go to school now." That beating did me some real good. I also slept really well after.

Sometimes when we played at home, a window would get broken. And a broken window for a labourer, with the money he makes, is a big deal. If someone had broken a window, they'd go to bed early that day. The idea was that our dad would have his first reaction while we were asleep, and so he wouldn't reprimand us. And then the next day, everybody would continue on with their lives as normal.

My dad was a great friend, a true friend. But we were afraid of him too, of course. We're a family of five siblings, four boys, and one girl. Our mother Resmigül passed away in 2004.

After my father died, I enrolled in night school. I was working during the day and going to school at night. One of my biggest regrets has always been that my dad never got to see me earn money, and that I never got to buy him clothes, nice stuff to wear. If only I'd had the chance to look after him.

When martial law was relaxed back in 1985-86, I put a commemorative notice in the paper for my father. I thought, when I had the notice published, that other families would see it and that together, we'd be stronger, but nothing really came of it. After that I continued putting regular commemorative notices in the paper. In Evrensel, in Cumhuriyet...

Then just recently, the press started to take a strange interest in 1 May 1977. Even some members of the mainstream media reached out to us, because the trial had turned into a circus of sorts. I was interviewed by a newspaper or two at the time; if you ask me though, they weren't doing it with good intentions. So of course their interest waned after a while.

I went to the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey [DİSK] about the trial once; but as far as I know, no countersuit was filed. At one point I tried to get together with the other families. I went to the Human Rights Association, which was in Aksaray at the time, and I told them I wanted to meet other "First of May Families" if possible.

I just wish the people responsible would be put on trial so that the whole world would hear and learn about what happened there that day.

Taksim was packed full of people that day and it was like everyone knew each other. Everyone was so happy. Normally you would never see Yıldız Slope so crowded. But that day, a massacre happened.

There in Taksim, where normally the police would come rushing if someone so much as raised their voice, on that day, volleys of gunfire were shot at labourers.

It's said that there were 500 thousand labourers that day in Taksim. The population at the time must have been 5-6 million. So what a huge proportion of the total that was, just think about it. The bourgeoisie were afraid of these people.

After I lost my father, I never missed a First of May rally. I always thought that if I didn't go, it would mean one less person, and I went to every First of May rally, for my father, and for all the labourers who were massacred. But my real motivation during all of this has been the knowledge that I am owed something.

I always thought, "The state owes me." This state owes me, first and foremost, because the state murdered my father. (TY/DB/VK)

About Tuğçe YılmazJournalist, editor, researcher. "1 May 1977 The Voices of Those Who Lost Their Loved Ones / 1 May 1977 and Impunity" she was engaged in this dossier as a researcher, reporter, editor and writer. Her articles, interviews and reports are published in outlets such as bianet, BirGün Book, K24, 5Harfliler, Gazete Karınca and 1+1 Forum. She graduated from Ege University, Faculty of Literature Department of Philosophy. She was born in Ankara in 1991. |

|

| This text was created and maintained with the financial support of the European Union provided under Etkiniz EU Programme. Its contents are the sole responsibility of "IPS Communication Foundation" and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. |

CLICK - 1 May 1977 e-book is online

The ones who lost their lives on 1 May '77The ones whose loved ones we could talk to: Ahmet Gözükara (34, teacher), Ali Sidal (18, worker), Bayram Çıtak (37, teacher), Bayram Eyi (50, construction worker), Diran Nigiz (34, worker), Ercüment Gürkut (27, university student), Hacer İpek Saman (24, university student), Hamdi Toka (35, Seyyar Satıcı), Hasan Yıldırım (31, Uzel worker), Hikmet Özkürkçü (39, teacher), Hüseyin Kırkın (26, worker), Jale Yeşilnil (17, high school student), Kadir Balcı (35, salesperson), Kıymet Kocamış (Kadriye Duman, 25, hemşire), Kahraman Alsancak (29, Uzel worker), Kenan Çatak (30, teacher), Mahmut Atilla Özbelen (26, worker-university student), Mustafa Elmas (33, teacher), Mehmet Ali Genç (60, guard), Mürtezim Oltulu (42, worker), Nazan Ünaldı (19, university student), Nazmi Arı (26, police officer), Niyazi Darı (24, worker-university student), Ömer Narman (31, teacher), Rasim Elmas (41, cinema laborer), Sibel Açıkalın (18, university student), Ziya Baki (29, Uzel worker), The ones whose loved ones we did/could not talk to: Aleksandros Konteas (57, worker), Bayram Sürücü (worker), Garabet Akyan (54, worker), Hatice Altun (21), Leyla Altıparmak (19, hemşire), Meral Cebren Özkol (43, nurse), Mustafa Ertan (student), Ramazan Sarı (11, primary school student) The ones only the names of whom are known: Ali Yeşilgül, Mehmet Ali Kol, Özcan Gürkan, Tevfik Beysoy, Yücel Elbistanlı The one whose name is unknown: A 35-year-old man |

The voices of those who lost their loved ones: 1 May '77 and impunity

Political panorama of Turkey-1977

Film industry worker Rasim Elmas, 41, died in Taksim

Construction Worker Bayram Eyi, 50, died in Taksim

Teacher Bayram Çıtak, 37, died in Taksim

High School Student Jale Yeşilnil, 17, died in Taksim

Teacher Kenan Çatak, 31, died in Taksim

Teacher Ahmet Gözükara, 33, died in Taksim

Teacher Hikmet Özkürkçü, 39, died in Taksim

Student-laborer Niyazi Darı, 24, died in Taksim

University student Nazan Ünaldı, 19, died in Taksim

Teacher Ömer Narman, 31, died in Taksim

Laborer Ali Sidal, 18, died in Taksim

Counterperson Kadir Balcı, 35, died in Taksim

Student Hacer İpek Saman, 24, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Kahraman Alsancak, 29, died in Taksim

Laborer Hüseyin Kırkın, 23, died in Taksim

Student Ercüment Gürkut, 26, died in Taksim

Public order police officer Nazmi Arı, 26, died in Taksim

Laborer Mahmut Atilla Özbelen, 26, died in Taksim

Factory worker Hasan Yıldırım, 31, died in Taksim

Itinerant salesperson Hamdi Toka, 35, died in Taksim

Security Guard Mehmet Ali Genç, 60, died in Taksim

Factory Worker Ziya Baki, 30, Died in Taksim

Laborer Mürtezim Oltulu, 42, Died in Taksim

Teacher Mustafa Elmas, 33, Died in Taksim

Student Sibel Açıkalın, 18, died in Taksim

Laborer Diran Nigiz, 34, died in Taksim

1 May 1977 & Impunity

'The state is implicated in this crime, perpetrators must be put on trial'

'If you can't find the killers, you can't remove the stain'

'The perpetrators of the 1 May 1977 massacre got away with it'

Remembrance as a matter of dignity and the fight against impunity

Who is hiding the truth and why?

-132.jpg)