Photo: Medine Mamedoğlu

Click to read the article in Turkish

"It is alleged that I appeared on a television broadcast in a city in Germany where I have never even dreamed of visiting. I have never been to that city, and this can be seen in my passport..."

The person explaining the inaccurate accusation against him in the indictment is Mehmet Şahin, one of the 15 Kurdish journalists who were released in the first hearing yesterday, after 13 months in pretrial detention.

In reality, Şahin is a teacher. After being dismissed from his profession through a statutory decree in 2016, he started working as a journalist. He primarily produces television programs.

During the trial, he refuted the allegations against him from 15 different angles. One of these allegations was the broadcast he supposedly participated in, which you just read about, in a city he never visited.

The prosecution's claim is that if you host programs on channels like Sterk TV and Medya TV, which are banned in Turkey, then "you are a member of a terrorist organization."

The first hearing of the trial, in which 18 journalists, 15 of whom were remanded in custody, are being tried, took place at the Diyarbakır 4th Heavy Penal Court. Due to the defense statements not being completed, the hearing continued into the second day on July 11. As someone coming from out of the city, I couldn't attend the second day because of this. It was impossible to find a flight from Diyarbakır to İstanbul; the flights had been cancelled. People could go to Elazığ and return to İstanbul from there, if they could find a seat. This, in itself, is a problem. There are plenty of flights to every corner of the country, but only three or four flights to Diyarbakır in certain days.

Anyway, even a single day is enough to feel the attitude of the court panel and the atmosphere inside and outside the courtroom. I say unfortunately because, as someone who frequently witnesses anti-democratic practices and unfair approaches in trials, witnessing this extraordinary system here is as heart-burning as Diyarbakır's scorching heat.

You can read news about what happened during the trial from here and here, of course, but I would like to share a few details with you from the hearing.

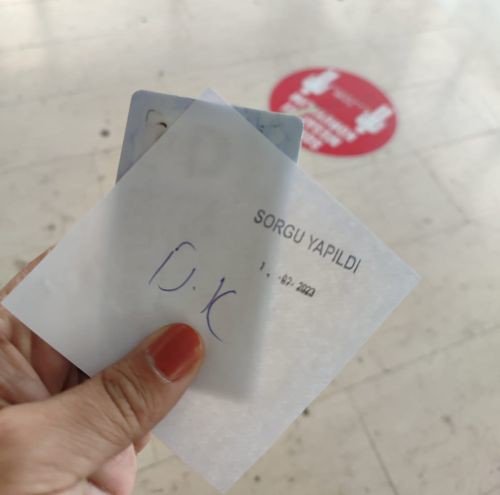

My name is Ü.K.

I recevied this paper with my initials after the ID check.

I recevied this paper with my initials after the ID check.

To enter the courtroom, you wait in a long queue, and when it's your turn, you enter through an iron door. It's a revolving iron door with intervals of bars.

As you enter, those bars can cause a bit of pain. When you come to a place for justice, a little pain is insignificant, so you continue on your way. Then they take your identification. They stamp a sentence on it saying, "No criminal record." Then, with that paper and your ID, you come to the second X-ray machine. You leave all your belongings again, give your ID and that slip of paper to the police, and enter.

The courtroom is crowded. There are the families and children of the 15 journalists, representatives from professional organizations who have come from different parts of Turkey, and plenty of lawyers.

We are all here. The presiding judge and the two accompanying judges are also women. They look at the courtroom with stern expressions. Resul Temur, one of the lawyers who has been closely following the journalists' situation in the region and constantly facing pressure as a result, mentions that one of the investigating prosecutors and one of the judges on the panel are married, which he says is an unlawful situation. He requests the recusal of the panel. All eyes turn towards the panel. They whisper among themselves with suppressed laughter. The decision is announced: "Your request has been denied."

The presiding judge quickly summarizes the 728-page indictment: "You are accused of hosting and producing programs for Sterk TV and Medya Haber TV, and a trial has been initiated against you for the crime of 'being a member of a terrorist organization'."

Even holding your cellphone in your hand is prohibited

The hearing begins with the presiding judge's warning: "Cellphones and computers should not be taken out of your bags." Throughout the hearing, she repeatedly raises her voice when uttering this sentence. We inform her that we are journalists and aware that audio and video recording is prohibited during the trials. We explain that we were aware that if we didn't comply with this rule, we wouldn't be able to attend the hearings. We mention that we work in İstanbul in this manner. Yet, she does not change her decision.

The 15 journalists are brought into the courtroom with their hands cuffed. Applause erupts in the courtroom. The families, the journalists, all of us applaud them. They have been waiting for this day for 13 months, or 400 days. They haven't appeared before a judge. The journalists wave to their families, and some children move to the front rows to get a closer look at their parents. Once again, the presiding judge raises her voice:

"If there is any further disturbance, we will hold the trial without spectators."

First, journalist Serdar Altan presents his defense. He questions why hosting programs has been deemed a crime. Isn't he right?

Not an indictment but a document of false accusations

It's not only Altan's defense; almost every journalist, in their defense statements, highlights the contradictions in the indictment one by one.

Of course, amidst all this, we hear the voice of the presiding judge turning the courtroom into a democracy carnival. "Be quiet, put your phones in your bags."

The judge, who has been keeping journalists behind bars for 13 months for practicing journalism, tells them to make their speeches shorter. These individuals, who have had the opportunity to refute the allegations they haven't uttered a single word about for 13 months, are being told "you're taking up too much time."

On the first day, we listen to the defenses of Ömer Çelik, Mehmet Ali Ertaş, and Zeynel Abidin Bulut. They all present their defenses in Kurdish. Translators occasionally get tired, and people in the courtroom step out and come back in again.

"He hasn't even seen his child yet"

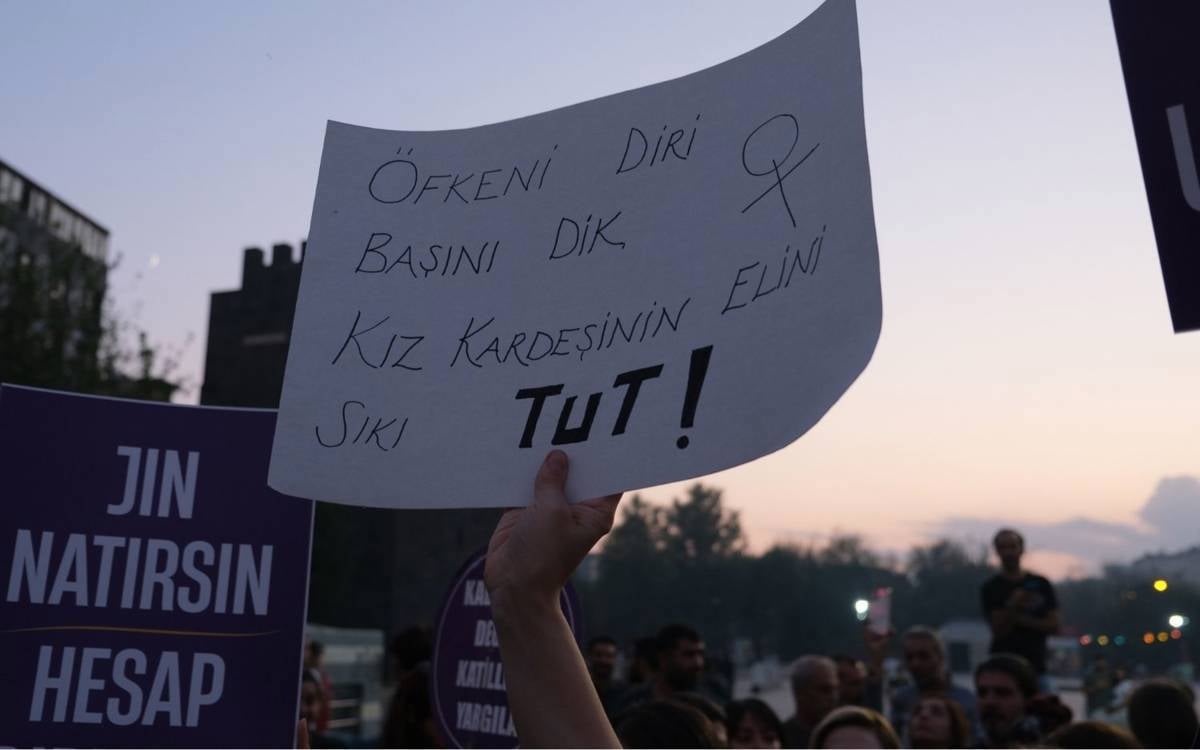

While all this is happening inside, the atmosphere outside is not much different.

Most of the families outside wait for news about their loved ones on the carpets they've laid under the trees. I notice a large group and ask, "Are you relatives of the journalists?" "Yes, my brother Mahsun is standing trial," one of them says. "He hasn't even seen his child yet. He was working in a job with social security; he didn't do anything secret."

.jpg)

This scene is probably not seen anywhere else in the country. The families of journalists have turned the area in front of the courthouse into a waiting zone. With this photo alone, the European Union shouldn't keep Turkey waiting in its waiting room. Because what is being tried here is merely journalism.

For the first time, I see a representative from the Journalists Association at a journalists' trial in Diyarbakır. It's Yusuf Kanlı, the president of the Ankara Journalists Association. He criticizes the arrests during the break in the hearing.

.jpg)

"We came here not to give an account to you but to demand accountability"

At the end of the two days, a release order was issued for all journalists. As journalist Altan stated in the courtroom:

"We are not guilty, we are the plaintiffs. We are the plaintiffs of journalism that has been trampled upon. We are here with our heads held high, not regretful. We have come here not to give an account to you, but to demand accountability from you. Why have you kept us away from our loved ones, the streets, and our profession for 13 months?"

Indeed, the release of journalists who have been held in prison solely for performing their jobs with evidence obtained through unlawful means for 13 months is not enough. This is an incomplete justice. We demand acquittal, not just release.

Journalism cannot be put on trial! (EMK/VK)

.jpg)

.jpg)