Click to read the article in Turkish / Kurdish

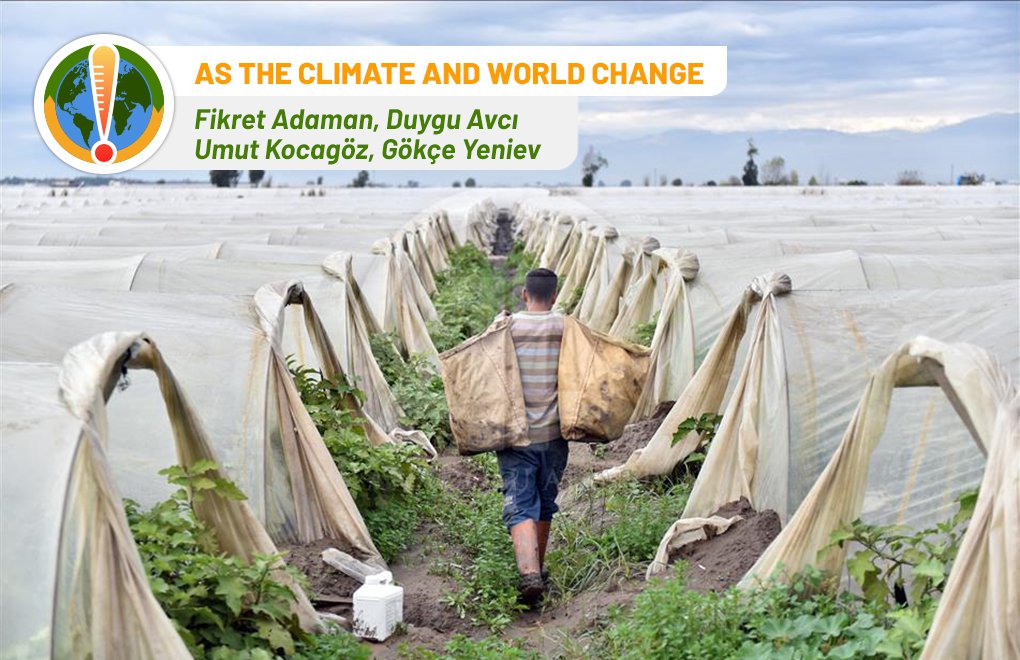

We don't have much time left to stop the climate crisis. The greenhouse gases that raise global temperatures are mainly caused by the use of fossil fuels (both in energy production and transportation), deforestation, industrial processes, the use of artificial fertilizers, and cattle breeding.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) emphasizes that the concentration of greenhouse gases, especially CO2, has risen to unprecedented levels in recent years.

The beginning of the increase in greenhouse gases -the negative transformative impact of the economic system on nature- dates to the 18th century. CO2 emissions in the atmosphere have increased by 50 percent since then.

In addition, the 18th century also marks a period in which many social transformations such as increasing inequalities between and within countries, the rapid commodification of labor, deepening poverty, and structural unemployment began to take place.

To express with reference to the famous economist-anthropologist Karl Polanyi, the commodification of labor and nature- and the reduction of both to production factors that have no meaning other than their economic value- have brought profound social and ecological problems.

Can it be solved with a reformist approach?

There are many different perspectives on climate change and solution proposals produced from these perspectives. While some of these offers seek answers within the current political economy, some stand out with their transformative demands.

Green growth, green technology, and emissions trading system practices can be given as examples of reformist approaches. They argue that with technological modernization and energy efficiency, we can separate economic growth from greenhouse gas emissions so that economic growth can happen without pushing the limits of the planet.

However, as empirical studies have shown, finding solutions to climate change within the system and limiting the temperature to 1.5°C compared to the industrial revolution is, to put it naively, dubious!

These approaches propose superficial solutions rather than focusing on structural problems holistically and depoliticize environmentalism. It is also doubtful to what extent these approaches can respond to ecological problems other than climate change and the social problems we have mentioned above.

Change the system

Those who adopt the slogan "change the system, not the climate"- a slogan we frequently encounter in the global climate justice movement, are included in the second group. This slogan indicates that keeping the temperature rise at 1.5°C and the transition to a net-zero carbon economy is possible only if we focus on the structural causes underlying the emission increases.

In fact, with this slogan, climate activists say that a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions is a must and emphasize the urgency of a systemic transformation.

On the one hand, this approach emphasizes the need to reduce total production and consumption. On the other hand, it aims to achieve a more just and egalitarian social order.

A proposal for a new path

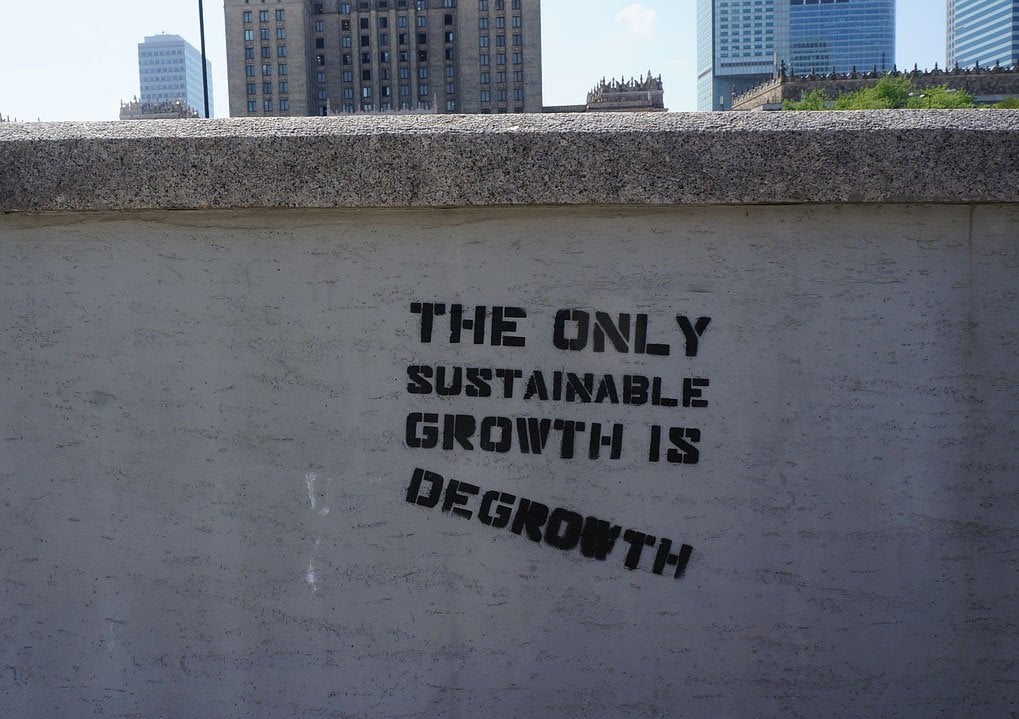

The subject of this article, degrowth, offers us an opening at this point. Degrowth is a concept that has been debated by academics, activists, and social movements for nearly 50 years.

The deepening of social and ecological problems of neoliberal capitalism after the 2008 crisis and its vulnerability to the existing climate, financial, political, and health crises that we are experiencing accelerated the search for solutions and revealed degrowth as a strong alternative.

Degrowth has begun to be questioned, adopted, and defended by a wide variety of social segments globally. It criticizes the ongoing growth obsession despite the global ecological crisis, increasing inequalities, and injustices. It is a call for a paradigm change that reveals that the search for relentless growth does not only produce ecological crises and inequalities but is intertwined with these problems and can exist only by depending on crises and inequalities.

The aim of the degrowth movement, in parallel with the climate justice movement, is not to reduce the same but to create a different world. Degrowth offers climate activism a new path on how we can make that systemic change:

• Degrowth is defined as a fair reduction of production and consumption that will increase human well-being and improve ecological conditions. Technological advances (for example, energy efficiency and enrichment of renewable energy sources) and behavioral changes (for example, taking the train instead of an airplane, supporting local food production and consumption) are crucial to prevent the climate crisis. However, even if we reduce the relationship between economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions, it does not seem possible to reset it. From this point of view, it states that economic shrinkage is essential to prevent the climate crisis.

• In the last 50 years, per capita income has increased from $750 to $10,000. However, as we all know, some countries and different segments could not benefit from this increase in a fair and equal way. Beyond that, the argument that 'injustice and inequality lie behind this growth' should be considered. Therefore, if the injustice and inequalities produced while growing are reflected in the intended degrowth process, downsizing will cause economic recession and depression. It means the unequal distribution of costs and the fragile segments of society will be affected very negatively by this situation. (Covid-19 has created shrinking in many places: shrinking. The cost has been reflected in different ways on the shoulders of different segments). From this point of view, degroth reveals the distinction between the unplanned and involuntary shrinking of the economy, which is expected to be brought by climate change in a growth-oriented system, and a planned and sustainable shrinkage in a way that protects human welfare and the environment.

• Degrowth demands the creation of a more equal society, ensuring the safety and livelihoods of all members. This, in turn, expands the political space to produce policies for climate change and contributes to the social justice framework of the policies. The inequalities experienced today are one of the reasons behind the production of fear-based populism policies and the establishment of hegemony by feeding the growth fetishism of the governments- and perhaps the most important one. Degrowth can prevent the climate crisis by redefining the priorities for society. It can carry climate policies to large segments by ensuring the solution proposals on this path are adopted by all.

• Degrowth does not offer the same prescription for every country and every sector within countries. It does not problematize economic growth that will enable everyone to meet their basic needs (such as food, shelter, health, education). On the one hand, it opens for discussion on which sectors the economic growth that will meet the basic needs is indexed and the ecological and social effects of these sectors. On the other hand, by proposing a modest way of life, it demands that the wealthy people, in particular, reduce their consumption, which we can call sumptuous, and therefore shrink the sectors behind this consumption. He underlines that sectors such as care, whose importance has emerged dramatically with the Covid-19 pandemic, should not shrink but grow and sit at the center of the economy. To eliminate the negative effects of shrinkage in the labor market, it offers a reduction of working hours as a solution.

The path to degrowth: So, how do we do it?

Degrowth is not just economic. It can be seen as a metaphor for the need for change on many levels. The prerequisite for initiating this change is identifying and diagnosing what is done well and what is not.

Measuring well-being in terms of economic growth is misleading in many ways; there are some problems associating success with these figures. The economic growth index rises when laundry is tumble dried rather than in the sun and jumps during weapon production. It is considering neither the 12.5 billion hours of care work performed each day- mainly by women and girls- nor the environmental impact of economic activities.

On the other hand, it does not consider how much time employees can spare for themselves, how healthy/unhealthy the working environment is, and the degree of poverty and/or unemployment. Borrowing on debt and achieving high growth is perceived as welfare maximization.

This long list tells us that we need to get rid of linking social and economic success to growth figures as soon as possible and start considering a measurement that prioritizes human well-being, emphasizes justice and equality, and does not exclude the environment.

In other words, we need to get rid of the approach that we can solve any problem with high growth figures. A new measurement method will also show that economic growth is no longer meaningful once we consider social and ecological impacts.

The point we have reached is how to draw the path of degrowth. It is necessary to create different and complementary policies at different levels. A post-growth economy needs a set of concrete and widely approved macroeconomic policies, and a cultural transformation is essential for change to be lasting.

Local and macro policies

In the absence of local action, macro policies can come as an imposition from above; and the desired cultural transformation is interrupted. On the other hand, in the absence of macro policies, the boundaries of local efforts are drawn very narrowly, and the local remains incapable of determining the general course in the last instance. Therefore, it is crucial to create a roadmap that considers the synergy between local and macro.

In this context, it is necessary to construct a more inclusive, fair, and equitable production structure and establish processes at the sectoral level. First, we should abandon today's neoliberal approach- which does not have much concern except for maximizing profits and increasing the growth figure in the narrow sense. Instead, with various policies (tax structure/incentive mechanisms/infrastructure opportunities, etc.) and regulations to be made in the labor market (regulation of working hours, etc.), we should follow a degrowth path in a fair, equitable, and human and nature-centered manner.

The way to do this is to subject the existing political-economic system to a structural change. The realization of the planned degrowth will only be possible by designing the economic life in a planned setting. What is expected here is that the planning is formed by participatory methods, not in a hierarchical structure.

At the same time, the degrowth movement should be implemented at the local level. Degrowth can come into being through moves such as supporting local productions, highlighting cooperative and solidarity practices, defending public/common spaces, and determining local resource allocation with a human and nature-oriented perspective and participatory mechanisms.

Such steps at the local level also provide a basis for the germination of a culture that favors modesty and supports solidarity practices instead of a consumption-based, self-centered approach.

Going back to Polanyi, the way to prevent the commodification of labor and nature is not to leave the regulation of economic life and in this context, especially the making of investment decisions to the logic of the market, and to create governance structures at local and macro levels that will make the society have a say in these processes.

The logic of the market, in the last instance, is an approach that puts social and ecological problems in the background, pushes them forward, and- if possible- puts the burdens on the shoulders of others. We believe that the degrowth approach is a target that should be focused on is creating an alternative to this.

(GY/FA/EÜ/VK)

"As The Climate and World Change" article series*

Our life becomes history while we live! - Ömer Madra

1 / A country outside of the global climate policy: Turkey - Ebru Voyvoda

2 / Climate change, securitarian policies and ghosts - Özdeş Özbay

3 / Turkey's energy policy: Indigenous at home, Blue Homeland in the world - Emre İşeri

4 / The impact of climate crisis and fossil fuels on child health - Çiğdem Çağlayan & Funda Gacal

5 / We will see beautiful days, coal-free and sunny days - Elif Ünal

6 / Either capitalism or the future - Tuna Emren

7 / The three pillars of climate journalism: Science, politics, and social justice - Ece Baykal Fide

8 / Bringing science, struggle, and art together - Yasemin Ülgen

9 / Clean energy or betrayal? - Serkan Ocak

10 / It is time to say stop economic growth- Fikret Adaman & Gökçe Yeniev

11 / When climate refugees knock on our door - Mehmet Mücteba Göktaş

13 / Climate crisis affects women, women affect climate struggle - Merve Özçelik

14 / Climate fiction in literature- Buket Uzuner

15/ Dr. Faustus and children in the age of fire- Ömer Madra

* This series of articles is published with the financial support of Oslo Metropolitan University (OsloMet) Journalism & Media International Center.