Click to read the article in Turkish

This summer is not going well. It’s not that the sun, sea, holidays, relaxation, reading, and shrinking work-load provide no comfort, but the truth is that we are not ok. This is our fundamental reality these days. No matter how we try to dress it up, it’s still ugly. Summer and holidays are just more clothes.

Summer is the season that Hilmi Yavuz called “magic”. The way I personally have tried to suppress the anger we experienced in recent weeks, with the detention of this great, 80-year-old poet, is by clinging tightly to his poems. Fortunately he was not arrested, and we took a deep breath of relief. It was not to last. Immediately afterwards, Aslı Erdoğan was detained and arrested. Was I surprised? No. I would be lying if I were to say I didn’t believe it, because I very much do.

Nothing can surprise me in this country anymore.

Perhaps this thickening of my skin – of our skins – is what it means to grow up here.

Every day I look at what’s written and drawn about Aslı Erdoğan. For example, Aslı’s friends began a written “watch” with the aim of supporting her. Every day, a writer writes something in defence of freedom of expression. I ask myself, what can be more hopeful than this? Aslı Erdoğan is not alone.

Perhaps all these events, and the writings and drawings about them, will spark the curiosity of those who have never heard Aslı Erdoğan’s name nor read any of her books. Is that just extreme optimism? So be it. It’s better than going crazy.

In the meantime I too started to re-read Aslı Erdoğan’s books, as I did with Hilmi Yavuz. I think this is my way of participating. It’s the only thing I can do. One can support a writer by understanding them, by breathing in their world afresh, by trying to hear their voice once more. If we fail to do so, it is all too easy to slide into anger. One must not give up. This is probably the most fundamental thing we have learned from these writers.

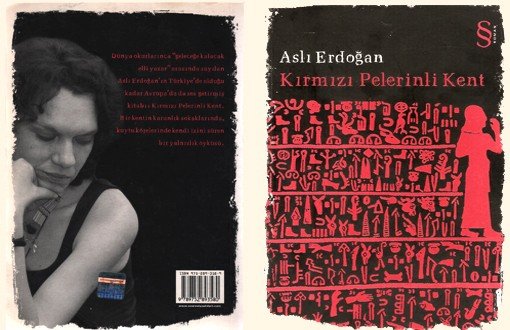

The City in the Crimson Cloak (Kırmızı Pelerinli Kent), The Shell Man (Kabuk Adam), The Stone Building and Others (Taş Bina ve Diğerleri), In the Silence of Life (Hayatın Sessizliğinde), The Miraculous Mandarin (Mucizevi Mandarin), and many more...

“Now close your eyes. I will count to ten in my head. When I say ‘ten’, you will be in Rio. But I won’t tell you when you need to open your eyes”

In The City in the Crimson Coat, Aslı Erdoğan follows the trail of a woman called Özgür (free) through the streets of Rio de Janeiro. But this Rio is different from the city that we imagine – a spooky, bleak, oppressive, mysterious, dangerous Rio, a Rio in which the sound of gunfire and clashes does not cease, a Rio where rape, drugs and murder run amock. She writes of windows left open night and day due to the heat, of grasshoppers, lizards, and cockroaches, of dischevelled and filthy houses beside the jungle.

In fact, Özgür herself writes The City in the Crimson Coat;

“I turned to writing because I could find no other bulwark against death, against this city which puts the value of a human life at 100-400 dollars.”

In this novel, we follow Özgür, her mother, her femininity, her masculinity, her loneliness, life and death – in short, her relationship with the city.

On the night she understands that she has fallen in love with the city, Özgür is killed by a busty woman. Rio becomes the place where she chases her death, maybe even the place in which she attains it. She surrenders to death as she awaits her rebirth inside the city.

“Death, which defies arithmetic, was stemming from a personal tragedy.”

The novel has many elements that can be described as psycho-political. But in order to see and analyse these we must remove ourselves from the novel itself. Because of all these goings on, when I re-read the novel I couldn’t take myself out of it. Nor did I want to. With every line that I read, and every space between them, the more it seemed that the city in the crimson cloak was in fact here. Once more I stood in admiration of Aslı Erdoğan’s bravery, creativity, strength, and the psychological portrait that she had weaved.

This sentence from the book is telling:

“’As long as I am able to write, I cannot say all is completely lost,’ she thought. ‘The true City in the Red Cloak is not a text to be read whilst Chopin’s nocturnes turn on the gramophone – it cannot be. Because gunfire can be heard in the places where I write.’”

As I was writing this article, a beautiful breeze began to blow. The season has already started turning; the wind is heralding the Autumn. I love the wind, because it scatters. It doesn’t hang on, it carries. It doesn’t leave things fixed. If you leave a place to the wind, few things will remain.

I love it also for the expression, “What was once there is no longer” (“Yerinde yeller esiyor”). Wind is a very important symbol of change and movement. I know that the wind will change direction. Nature shows us as much. Nature is the most concrete example of change. I know it will change. The wind will carry utterly new wonders, dissolve our anger, and increase our hope.

The season will change! (TI/HK/PS)

* Source: Kırmızı Pelerinli Kent, Aslı Erdoğan, Everest Yayınları, 2014, 144 s.