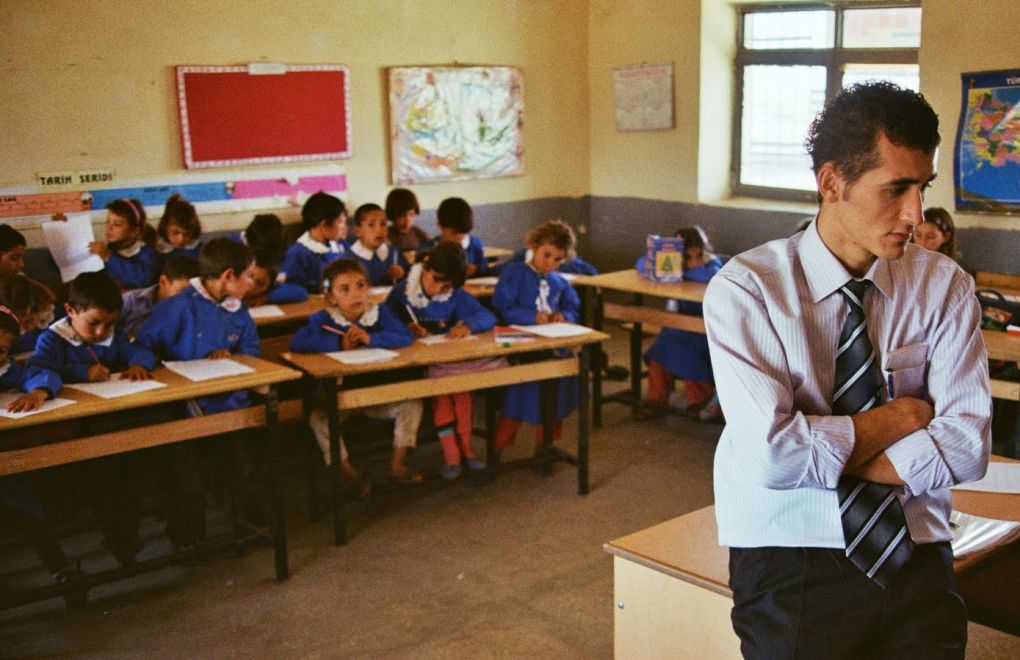

* Photo: From the movie "On the Way to School"

Click to read the articles in Turkish / Kurdish

Today is February 21 International Mother Language Day. When this day was still approaching, five teachers of "Living Languages and Dialects" spoke to bianet about their own struggles for their mother languages as well as their experiences as teachers from February 17 to 20.

Elective courses in mother languages began in Turkey in the 2012-2013 school year. But, what is the latest situation in these courses? Are these courses enough? What are the reactions and feedback of students and their parents? Here is a snapshot of the remarks of five teachers:

'Lack of teachers is the most important problem'

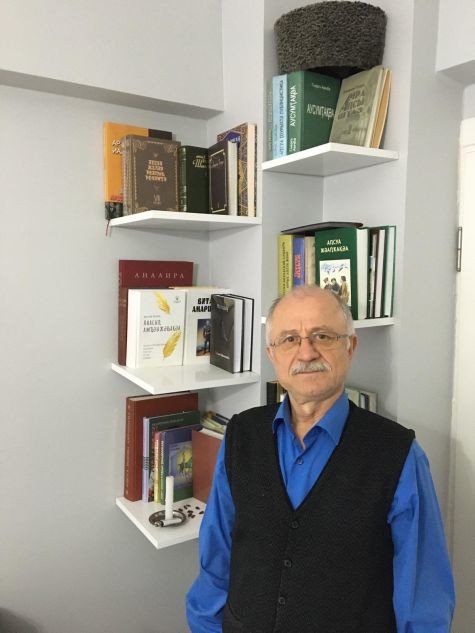

* İrfan Okuyucu

İrfan Okuyucu (Ahocba), a teacher of Abaza language, tells us that he started teaching the language as an elective course in Adapazarı in the 2014-2015 school year. He went to his classes all year round by covering 70 kilometers and changing three vehicles. While his monthly salary was 60 lira, he had to spend 460 lira per month for transportation expenses:

"The most important problem is the lack of teachers who will give the classes. Even when there is, it needs to be noted that no one would work for that salary (60 liras per month in 2015)."

Referring to his own struggle for his mother language, Okuyucu says, "Before I went to primary school, I did not even know the existence of another language. I came to know Turkish at primary school."

Becoming literate in his mother language thanks to a teacher training course offered by the Caucasian Associations Federation (KAFFED) in Ankara, he has been teaching the language since 2015.

'Cooperating with the homeland is important'

According to him, there are certain considerations or problems that eventually lead to a low demand for the course:

Sone parents fear that "their children will be regarded as separatists by some chauvinist teachers and they will be asked whether they are Turks or not."

With mobile teaching, students living in villages are sent to schools in city centers. If the schools at villages remained open, there would now be an opportunity to open at least 30 classes in 69 villages of Adapazarı.

Coupled with a lack of awareness, assimilation increases with urbanization.

With living conditions getting harsher, parents prioritize a good school, a good education, a good profession, thinking what good it would do their children to learn their mother languages.

Concluding his remarks, Okuyucu emphasizes the importance of cooperation with the homeland to increase the participation of students, to help them to practice the language in their homeland as part of projects and summer camps and to provide them with more teachers and teaching materials.

'...It was a moment beyond description'

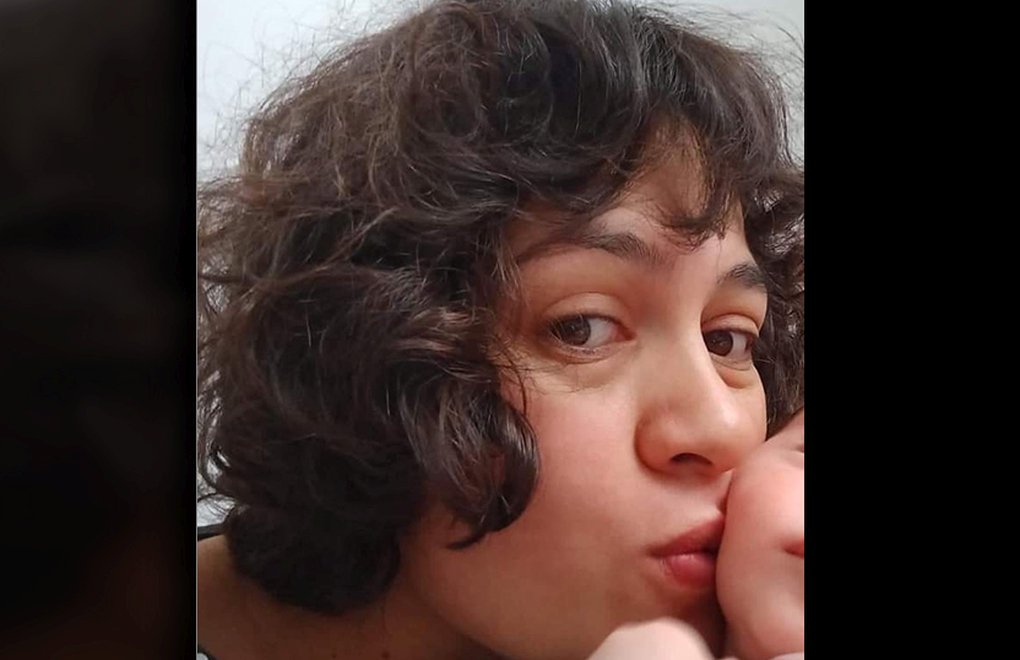

On the second day of the interview series, a Kurdish-Kurmanjî teacher who prefers to remain anonymous told us about his own story and struggle as well as his teaching experience.

When he remembers the first day of the class, he expresses his feelings in following words: "I was incredibly excited at my first class. Entering the class and saying them 'roj baş'... It was a moment beyond description."

When we ask him about his experience as a teacher and his struggle for his mother language when he was younger, he recounts them briefly as follows:

"If we do not attend the class, it will be closed immediately and replaced with another elective course. That is why we cannot even ask for appointment to somewhere else for feat that the course will be closed. Since the attempted coup on July 15, 2016, only one or two Kurdish teachers are appointed, sometimes none at all... There are now innumerous Kurdish teacher who cannot be appointed despite graduating from a four-year Department of Kurdish Language and Literature.

"When I started primary school myself, I was subjected to discrimination due to my identity. I did not know Turkish when I started school, I was subjected to physical and psychological pressure of both teachers and students.

"As for my university years, I was expelled from university because we demanded education in the mother language. Following a lawsuit we filed, I returned to school with a court verdict.

"After I graduated, a friend of mine told me about the Department of Kurdish Language and Literature at Artuklu University, where I started my Master's studies. It was a happiness and victory beyond description that the struggle that I started in university years came to this point."

'If courses had been opened 50 years ago...'

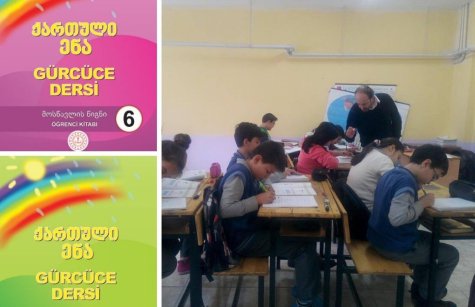

Mustafa Kolat, a teacher of Georgian language, says that when they first opened the course, they visited potential students and their parents, informing them about the course and telling them that learning one's mother language was a right. They were even asked "whether Georgian would be spoken in heaven or not" at that time.

According to Kolat, if this language had been taught 50 years ago, the class would still be opened even when the minimum number of students had been 20, rather than 10, as it is the case today.

"But, in the urbanized world of today, I do not think that this practice can be put into effect, except for some exceptions", Kolat tells bianet.

'Elective courses are like springs of life'

Muzaffer Çağlayan, a teacher of both Turkish and Zazaki, says,

"The source of teachers is clear anyway. When we look at the number of Living Languages and Dialects teachers appointed, we see that the allocated quota is not enough, it is indeed quite absurd.

"It is very difficult for children to learn the language in their all aspects in a couple of hours. All in all, there is an insufficiency in this field."

Çağlayan also shares some anecdotes from his own struggle for his mother language, putting an emphasis on the importance of education in mother languages in following words:

"When I look back on the day when I went from the village to the city (for secondary education), I see it as the day when I signed the death warrant for my mother language.

"In fact, cities are like whirlpools when it comes to the assimilation of cultures. In order to save oneself from this fatal and destroying climate of cities, cultural and contemporary values of nations should be evolved into educational institutions where these can be kept alive.

"And for us - It might sound very radical. It doesn't matter - the only way to do this is the education in mother languages. For our language, which has been thrown into blind holes and abandoned in darkness and whose whistles have been shackled, elective courses are like springs of life.

"In a two-hour elective course, we can make love with our mother language only evasively. I believe that education will be given in our mother language. If not today, then tomorrow... Because no rights can be deemed an injustice."

'Some parents asked if the course was legal'

Yılmaz Tokmak, a teacher of Adyghe language, is one of those who consider themselves lucky as he was born in a village where everyone spoke his mother language. "I am a person who did not have to struggle to learn his or her mother language", Tokmak tells us and continues as follows:

"Because I was born and raised in an environment where my mother language was spoken as a whole. In my childhood, if you are in the village, there was no such problem. I consider myself very lucky in that respect.

"When I started primary school, I met Turkish, which did not cause any problems in my educational life. As someone who saw the times when the use of mother language was almost forbidden, I welcomed it."

He started giving his first Adyghe lessons in the 2018-2019 year, when 10 students at his school chose the course as an elective:

"I was perhaps more excited than students on that day. We had our classes in a good environment as the school administration arranged a classroom for us. Two hours are - of course - not enough, but whatever students can learn is a win for us.

"Students are willing, but parents need to be convinced. There are definitely some reservations when choosing the course. From the ones asking whether the course is legal to the ones who question its benefit..." (AÖ/SD)